Part of a series of articles titled The Struggle for Sovereignty: American Indian Activism in the Nation’s Capital, 1968-1978.

Previous: The Trail of Broken Treaties, 1972

Next: The Longest Walk, 1978

Article

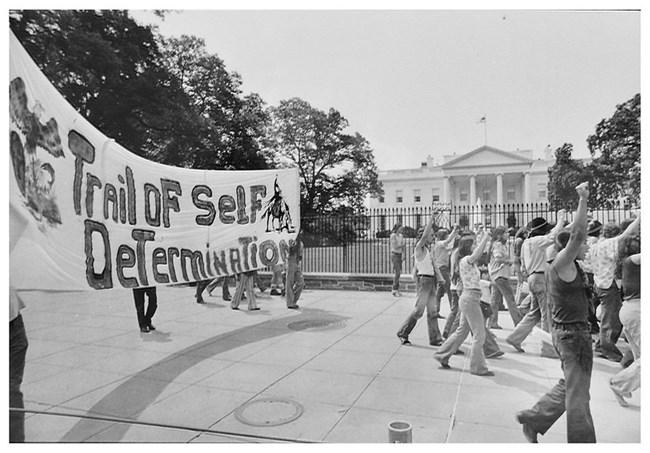

Photo by Glen Leach. D.C. Public Library Washington Star Collection

In 1976, the United States celebrated 200 years of independence. But the Bicentennial carried a very different meaning for American Indian communities still engaged in a struggle for self-determination. Although Native Americans had achieved significant legislative victories in recent years, a great deal of work remained to reverse nearly two centuries of federal Indian policy designed to eradicate tribal communities.

Four years after American Indian demonstrators occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs, activists once again embarked on a cross-country caravan to demand Native rights, this time amid the celebrations of the Bicentennial. They carried with them the Twenty Points program that framed the previous Trail of Broken Treaties in 1972, hoping to present it to Congress and President Ford. The goals, as before, were to get the federal government to honor past treaties and commitments to Native peoples and to replace the Bureau of Indian Affairs with a government agency elected by and for Indian peoples, as outlined in the Twenty Points.[1] Of particular concern was economic self-determination and the control over resources on tribal lands. As one participant warned, these times were “critical” because of the vast resources of coal, oil, and timber on Native lands in the West. He warned that if the self-determination movement did not succeed, the BIA would lease these lands with or without tribal approval.[2]

Largely overlooked in the press amid the celebrations of the Bicentennial, government officials paid close attention to the Trail of Broken Treaties. They were on high alert for any indication of a repeat of the events that led to the takeover of the BIA in 1972. Although 1976 demonstrators were tame by comparison, their presence at the 200-year celebrations sent a signal to Washington bureaucrats that the movement for Native American rights would continue until there was real change in U.S.-Native relations. And although the Trail of Self Determination is often forgotten in the history of the Native American rights movement, in many ways, it presaged the struggles over land and resources that would continue well into the twentieth century.

The lone caravan set off from the Yakima Nation in Washington State in June 1976, following the route of the Bicentennial Wagon Train, which signified in reverse the movement of settlers who rode covered wagons in their expansion westward.[3] Along the way, the Indian caravan was joined by members of other Indian nations, including the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux of South Dakota and the Wolf Point Sioux and Blackfoot of Montana.[4] They were also joined by allies from the Chicano movement, who were concerned with their own treaty rights from the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.[5]

The caravan was an opportunity both to generate publicity for the group’s demands and to educate one another on the issue of sovereignty. Mid-way through their journey, the caravan stopped in Lawrence, Kansas, for a week of conferences and workshops at Haskell Junior College, one of the oldest federal schools for Native Americans. But the caravan was not just about government reforms. Gene Heavy Runner, of the Blackfeet tribe in Montana, said that the caravan was also a spiritual movement: “Our spiritual heritage is all that has kept what remains of the Indian way of life alive,” he said.[6]

Compared to the previous Trail of Broken Treaties, the 1976 caravan was small, numbering perhaps 150 people when they first arrived in Washington. With the occupation of the BIA on their minds, however, federal officials kept the caravan under constant surveillance as it made its way across the country. Coordinating with state patrols, federal agents created a squad to deal with the “Indian scare.” Their concerns were unfounded, but the potential for friction was ever-present. Upon reaching St. Louis, the National Park Service ejected the caravan from Gateway Arches, where the group had set up tipis at the symbolic gateway to the West. Later, however, the Park Service reversed course, issuing a special camping permit that allowed for the demonstration.[7]

The caravan arrived in Washington, D.C. on the eve of the Bicentennial, July 3, 1976, setting up camp at the American University soccer field and the Piscataway Indian Center. The following day, they gathered in front of the White House, their numbers having grown to 300. To the sound of a beating drum, they demanded a meeting with President Gerald Ford and a joint session of Congress to establish a new system of Indian self-government and greater control over their natural resources, but to no avail.[8]

Amid the celebrations of the nation’s 200th anniversary, the Indian protests received little press coverage until Secretary of the Interior Dennis Ickes ordered the arrest of 54 of the caravan participants. The group had gone to the Bureau of Indian Affairs building at 1951 Constitution Ave NW seeking a tour of the building at the center of the 1972 protests. The group’s arrival set Department of Interior officials on edge, recalling the events of four years earlier. They denied the group’s request for a tour and closed the building, sending its 200 employees home for the day. The group was assembled in the parking lot near the rear door of the building when the Federal Protective Service ordered them to clear the property. When the group refused, they were arrested without resistance.[9] In all, 16 men, 16 women, and 22 youths were arrested.

Despite the arrests, the Trail of Self-Determination protesters continued to hold demonstrations in front of the White House throughout the month of July. The D.C. Corporation Counsel quickly dropped the charges and the group met with BIA officials the following day. Ultimately, BIA officials refused to make any commitments to their demands, and the demonstrators returned to their homes without further incident. But their journey was far from over.

[1] Maurice White, “Indians Break Camp at Temple Stadium, Head For Washington,” Philadelphia Tribune, 3 July 1976.

[2] “Trail of Self-Determination Caravan Heads Toward U.S. Capital in Serious Effort to Bring Changes,” Akwesasne Notes, 30 June 1976.

[3] “Bicentennial Wagon Trail Pilgrimage to Pennsylvania 1975-1976,” Bicentennial Commission of Pennsylvania, 1976, Ford Library.

[4] Jessica Brodt, “Native American Delegations, Diplomacy, and Protests at the White House,” White House History, 25 September 2020.

[5] “Trail of Self-Determination Caravan Heads Toward U.S. Capital in Serious Effort to Bring Changes,” Akwesasne Notes, 30 June 1976.

[6] “Trail of Self-Determination Caravan Heads Toward U.S. Capital in Serious Effort to Bring Changes,” Akwesasne Notes, 30 June 1976.

[7] “Trail of Self-Determination Caravan Heads Toward U.S. Capital in Serious Effort to Bring Changes,” Akwesasne Notes, 30 June 1976.

[8] Jessica Brodt, “Native American Delegations, Diplomacy, and Protests at the White House,” White House History, 25 September 2020.

[9] Wilson Morris and Paul Hodge, “54 Indians Seized, Charged Following Argument at BIA,” Washington Post, 8 July 1976.

Part of a series of articles titled The Struggle for Sovereignty: American Indian Activism in the Nation’s Capital, 1968-1978.

Previous: The Trail of Broken Treaties, 1972

Next: The Longest Walk, 1978

Last updated: June 26, 2024