Part of a series of articles titled Travel El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail: Essays .

Article

Traditional Groups along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro

In 1598, as Spanish colonizer Juan de Oñate led the first expedition to establish El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro north from Mexico into New Mexico, he made a surprising find: watermelon. Unlike other Old World foodstuffs that Oñate had planned to transplant to the northern frontier, the fruit already was being cultivated by New Mexico’s Pueblo Indian tribes alongside such traditional Pueblo crops as beans, corn and squash.

For Oñate, the surprise was that the fruit had reached New Mexico before he arrived to claim the region for the Spanish Crown. Watermelon had been introduced earlier in the Americas during the Spanish conquest. Some scholars believe the Pueblos obtained the fruit as a foreign trade item along footpaths that linked New Mexico’s Rio Grande tribes to tribal peoples in the Southwest and Mexico. Others think that Francisco Vázquez de Coronado could have introduced the seeds during his 1540-42 exploration of the Southwest.

Recognizing the crop as an important new agricultural resource, the Pueblos gave it space to grow within their diverse cultural landscape. Thus, when Oñate arrived in 1598, the Pueblos were simply living as they had for centuries in New Mexico—employing resources gained through encounters with other indigenous peoples and cultures via ancient, far-reaching routes of travel, communication and trade.

Words like “discovered” and “settled” are widely used in the historical narrative of the Spanish conquest. But the rich agricultural traditions that existed prior to the arrival of the Spanish in New Mexico underscore the reality that the Spaniards relocated to long-settled lands of deeply rooted Indian communities with proven cultural and ecological resources. There were no pack animals or wheeled vehicles to support trade in the Southwest before the Spaniards’ arrival. Yet indigenous peoples had developed and maintained significant communication routes that over centuries supported the longevity and sustenance of tribal cultures and communities.

Reports by early Spanish explorers of local trails that provided passage into unknown lands were central to Spain’s decision to move into the region. Thus, as Oñate extended the length of El Camino Real from Santa Barbara in northern New Spain to the northern Rio Grande Tewa pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh, he depended on the same general route that traditional peoples depended on to deliver trade goods and to communicate with other tribes.

The route linked a chain of pueblos along the Rio Grande corridor. This brought the Spaniards into direct and sustained contact with Pueblo and Athabascan tribes. Though clustered in the same region, the Pueblos comprised distinct and separate tribes united by common Piro, Tiwa, Towa, Keres, Tewa and Zuni languages. Anthropologists believe that Athabascan tribes of the Navajo and Apache migrated to the Southwest as early as the 13th century from the interior of western Canada, Alaska and the Northwest coast.

Today, while many of the pueblos mentioned in historic records of El Camino Real no longer exist, other pueblo and tribal communities associated with the trail thrive as living tribes. Their history up to the present, combined with archeological documentation of precontact and post-contact historic pueblos, represents a continuum of American Indian life on El Camino Real that makes it unique among other U.S. National Historic Trails with tribal history.

Incorporating an Indian Narrative

Understanding the historic connections and contributions of American Indians and other traditional peoples to El Camino Real is vital to fully understanding the trail’s cross-cultural character and influence in local, national and international history. Understanding how contemporary tribal peoples perceive and relate to El Camino Real is equally vital to its future preservation.

To that end, as part of its preservation, protection and educational mission for the trail, the National Park Service (NPS) hosts “listening sessions” that bring together diverse tribal representatives to discuss and define for themselves their relationships to El Camino Real (as well as to other U.S. National Historic Trails). The listening sessions are intended to encourage dialogue among Indian stakeholders about life before and after El Camino Real. Ultimately, the goal is to incorporate an Indian narrative into the story and interpretation of El Camino Real that recognizes the trail’s impacts, both good and bad.

“The Camino Real is a most important trail that ultimately impacted tribes throughout the U.S.,” says NPS Tribal Liaison Otis Halfmoon (Nez Perce), who leads the listening sessions. “History often forgets that time period, but our children need to know.”

According to Halfmoon, the duration and direction of El Camino Real give the trail particular significance. The trail’s south-north orientation and movement of goods profoundly, and positively, altered the cultural and ethnic character of Southwestern tribal life, allowing for a unique merging of European and indigenous influences from throughout the Americas.

For example, the Spanish introduction of the horse to Indian culture was a contribution that came from the south and ultimately benefited tribes across the U.S. Many of the European goods and cultural resources that were introduced from south to north, including new tools and technologies, agriculture and livestock, and international foods and trade items, also were adopted and adapted by Indian peoples.

At the same time, El Camino Real carried negative social and cultural impacts that suppressed, rather than supported, tribal cultures. “The Pueblos were open to things that were beneficial, especially in terms of trade,” Halfmoon says. “But the gains came with loss.” In this sense, everything El Camino Real carried north into Pueblo country—beginning with Oñate’s blazing of the trail upon ancient Indian pathways—both built up and tore down the foundations that tribal peoples had laid in the past.

Trade and Transformation

The south-north corridor that would become El Camino Real was part of a network of cultural routes that had long linked Southwest Indian tribes from New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado with one another and with important tribal cultures to the south. Among the most influential was Casas Grandes, in what is now Chihuahua, Mexico, which thrived as a major center of indigenous trade between the 13th and 15th centuries. Paquimé, the center of Casas Grandes culture, was the hub of exchange for items from Mexico.

A less tangible, but equally important, benefit of the cultural routes was their support of inter-tribal communications. At the time of the Spanish incursion, a number of pueblos were located along what would become El Camino Real near Socorro, Albuquerque and Santa Fe, and word had surely spread among tribes that intruders were soon to arrive. For the Spaniards, exploration along the trail inspired a flow of communications about the pueblos’ strong, localized community structures.

Early Spanish accounts depict advanced Indian civilizations living in multistoried adobe villages with complex social, religious and artistic traditions, and an evolved environmental understanding of the northern frontier. While these factors enhanced New Mexico’s appeal to Spain, so did the routes’ history of commerce and cultural exchange. Appropriation of the cultural routes would enable Spain’s driving aim to colonize and Christianize the Pueblo peoples.

Oñate moved his colony into the northern pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh, the first capital of New Mexico and the original terminus of El Camino Real. As El Camino Real was developed in the 17th century, the more centrally located pueblo of Kewa, which the Spaniards dubbed Santo Domingo, became the base for the Franciscan missionary effort. Mission supply caravans, which reached New Mexico about every three years, made their first stop at Kewa. From there, smaller caravans split off onto side roads to supply other parts of the province, including Acoma, Zuni, Hopi, Jemez and the missions of northern New Mexico. The wagons then returned to Kewa before moving back down El Camino Real to Mexico City loaded with local and regional trade goods.

After 1610, the caravans also moved goods from Kewa to Santa Fe, the new provincial capital and new terminus of El Camino Real. Colonial laws forbade Spaniards to occupy Indian pueblos, limiting settlement to three miles outside of a pueblo. The law made Oñate’s original selection of Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan) and Yunque (San Gabriel) too close for comfort. As the old capital was replaced with a new one, Oñate, too, was replaced with a new governor, Pedro de Peralta.

Religious Suppression and Revolt

Though he had accomplished the long-awaited task of colonizing New Mexico, Oñate was misguided in believing that local tribes were agreeable to the Spanish presence. One of his first acts as governor was to convene representatives of various pueblos at Kewa, where he asked leaders to vow allegiance to the Spanish Crown and obedience to the Catholic Church. The Pueblos were highly individualistic, yet Oñate believed the leaders had understood and united in their pledge to fully embrace a new way of life. He was wrong.

The missions were to provide religious instruction and military protection to the Pueblos. But as Catholic ceremonial goods were transported up El Camino Real on the mission caravans—including church altar screens, gold and silver chalices, clerical vestments, musical instruments, and tools for blacksmithing and other instruction in mission workshops, Pueblo religion was suppressed. Tribal peoples were forced into conversion as their sacred native religious items were burned publicly and some tribal priests were hanged as sorcerers. The Pueblos had little choice but to acquiesce to Catholicism, yet they preserved their religious practices by performing them in secret.

The mission effort involved other forms of exploitation by the Spaniards, including unfair taxation, interference in tribal government, and slavery. Although African slaves had accompanied the 1540 Coronado expedition into New Mexico, Spanish laws against Indian slavery were enacted in 1542. These solely allowed enslavement of non-Christianized Indians, as well as Indians at war with the Spaniards.

A few months after Oñate occupied New Mexico, however, slavery was used as punishment at Acoma Pueblo for rebellious acts against the Spanish Crown. Spanish soldier Juan de Zaldivar was killed at Acoma for demanding blankets and provisions from the tribe. Oñate ordered a punitive expedition that resulted in the brutal torture and enslavement of many Acoma men. Some 70 Acoma girls under the age of 12 were sent down El Camino Real and placed in convents across Mexico. In all probability, none ever returned home.

By the 17th century, captives and slaves were among the most valuable trade items on El Camino Real. Trade in Plains, Navajo and Comanche Indians captured in raids was especially brisk, and the auction of tribal peoples for use as household servants was a common activity on village plazas after Sunday Mass.

The gradual conversion of Pueblo tribes meant few Pueblo Indians were enslaved, though other devastating impacts on Pueblo life followed the course of El Camino Real. The road paved the way to the spread of European diseases and epidemics, including smallpox and cholera. Rampant disease reduced the Pueblo population by at least one-fourth during the 17th century, and even more during the 18th century.

By 1680, three generations past the Spaniards’ arrival, Pueblo life and culture were decidedly different. Spanish–Indian intermarriage was not uncommon. And some degree of mutual comfort had been achieved between the Spaniards and the Pueblos through the exchange and adaptation of trade goods and cultural resources. Still, discontent was rampant among the Pueblos. Just as the Spaniards depended on El Camino Real for communications between its local and global stakeholders, the road also made for improved communications between local tribes. When the call for revolt traveled to Pueblos up and down El Camino Real, pueblo residents united to drive the Spaniards out.

On August 10, 1680, the Pueblos attacked. Together they killed more than 400 settlers and soldiers and 21 Franciscan priests. As the survivors were forced 400 miles down El Camino Real on foot to El Paso del Norte, the Pueblos reclaimed New Mexico as their own.

Intermingling Cultures

The most successful Indian rebellion in North American history, the Pueblo Revolt left the Spaniards in exile in El Paso del Norte, now the Juárez, Mexico area, for twelve years. There, they and friendly Indian tribes who fled the revolt established a number of indigenous communities, among them Socorro del Sur and Ysleta del Sur. By 1693, led by new governor Don Diego de Vargas, the Spaniards were back in New Mexico. So were the Franciscans.

The friars rebuilt the mission system, though they now took a more open-minded approach to Pueblo religious traditions and cultural identity. Spanish-Pueblo relations slowly improved, and a new social structure solidified into a uniquely diverse New Mexican lifestyle. A more active and efficient El Camino Real played a critical role in restoring the province.

Beyond trade, the trail fostered an ethnic integration with local Spanish and Pueblo peoples of African-Americans, indigenous Mexicans and Mesoamericans, some Asians and other cultures that traveled and traded along El Camino Real. More than 20 terms denoted race and ethnicity in New Mexico between 1693 and 1823. Various factors determined ethnic identity, including a child’s birth community, paternity and an adult’s self-described ethnic identity. The Spaniards also employed a casta, or caste, system to identify Spaniards, Indians, Asians, blacks and others. Spanish and indigenous combinations were known as mestizos, while black-white mixes were termed mulattos.

Representatives of all races and ethnic mixes made a unique genetic and cultural imprint in New Mexico via El Camino Real, and contributed to all areas of the provincial society and economy. For example, after the deaths of many Pueblo Indians from Spanish-introduced diseases, mulatto slaves added their labor to the reconstruction of the province.

The captive classes also included Genízaros, or de-tribalized captives raised in Spanish households. These fully acculturated, Christianized Indians grew to become a significant socioeconomic class in New Mexican society. In the mid-18th century, genízaros formed their own communities on the fringes of the frontier, including Tomé and Belen in the south and Abiquiu and Ojo Caliente in the north. The group not only provided a protective, citizen-based buffer in less-settled areas of the province, they preserved traditions, such as religious feast days, that are central to both Spanish and Indian cultures.

Though many Pueblo communities were abandoned or destroyed in the face of the foreign incursion, others adapted and survived. The various languages among the Pueblo Indians continued to thrive. The Pueblo language base also expanded as Spanish became a prominent secondary language among tribes. With the 19th-century transitions of New Mexico to the governments of Mexico and the U.S., and the introduction of American trade along El Camino Real, English became part of tribal culture as well.

Encouraging Tribes to Tell Their Stories of El Camino Real

El Camino Real’s contributions to tribal life and culture are undeniable. Still, the wounds of the Spanish conquest among New Mexico’s tribal peoples run deep, and for some, will never heal. One tribal representative taking part in a National Park Service listening session called it El Camino Triste, the road of sadness.

Respect for the sovereignty and independence of living Indian communities is an important part of NPS efforts to engage modern-day visitors in experiencing the trail. Educating visitors about the histories of New Mexico’s Indian peoples, as well as the histories of the Indian communities of Ysleta del Sur and Socorro del Sur in West Texas, is essential to fostering a full and true understanding of the trail. Thus the NPS travel itinerary of 17 significant El Camino Real sites highlights the trail’s important and enduring connections to Indian country.

NPS listening sessions and other tribal initiatives will continue to provide important information about how best to tell the Indians’ stories of El Camino Real. By fostering dialogue among members of different tribes, the efforts ensure that the voices of tribal peoples are heard alongside those of historians, archeologists and anthropologists who have traditionally interpreted El Camino Real.

“We view this as an opportunity not only to teach the youth about the trail, but to introduce older tribal members to the trail as something that has contributed to the continued life of the tribe,” says NPS Tribal Liaison Otis Halfmoon. “It also brings members of various tribes together to share their unique knowledge and experience of El Camino Real.”

With tribal participation, Halfmoon says, NPS education and enhancement efforts on El Camino Real can be a win-win for all cultures involved in the history and future of the trail. “The idea is to honor all cultures whose lives were touched by the Camino,” he says. “In one way or another, we are all part of the trail.”

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.

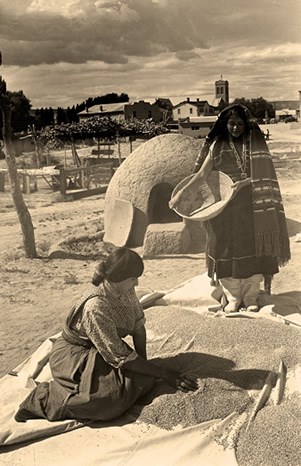

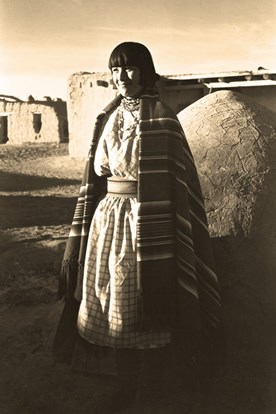

Photo by T. Harmon Parkhurst. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA. Neg. # 002491)

Tags

- el camino real de tierra adentro national historic trail

- el camino real de tierra adentro trail

- heritage travel

- heritage tourism

- discover our shared heritage travel itineraries

- historic trail

- heritage travel itineraries

- national trails

- new mexico

- new mexico history

- texas

- texas history

- indigenous heritage

- indigenous history

- indigenous people

Last updated: July 12, 2020