Last updated: November 4, 2020

Article

Tracking the Return of River Otters: First Results From a Long-term Monitoring Project

© Catie Clune / Photo 12808845 / iNaturalist.org / 2018-01 / CC BY

Carroll, T., Hellwig, E., Isadore, M. (2020) An approach for long term monitoring of recovering populations of Nearctic River Otters (Lontra canadensis) in the San Francisco Bay Area, California. Northwestern Natruralist 101(2), 77-91.

October 2020 - Today, observant Bay Area park visitors may spot North American river otters swimming, hunting, or playing along waterways throughout the area. This was not always the case. Otters were wiped out from the area in the 19th century by fur trapping, habitat loss, and pollution. Their return to the area is not only a visual treat but a positive indicator of ecosystem health. However, until recently there were no analyses of the otter recovery describing where they’ve been and how they’ve been doing. Scientists at the River Otter Ecology Project are changing this with the help of a team of community-scientist “otter spotters”.

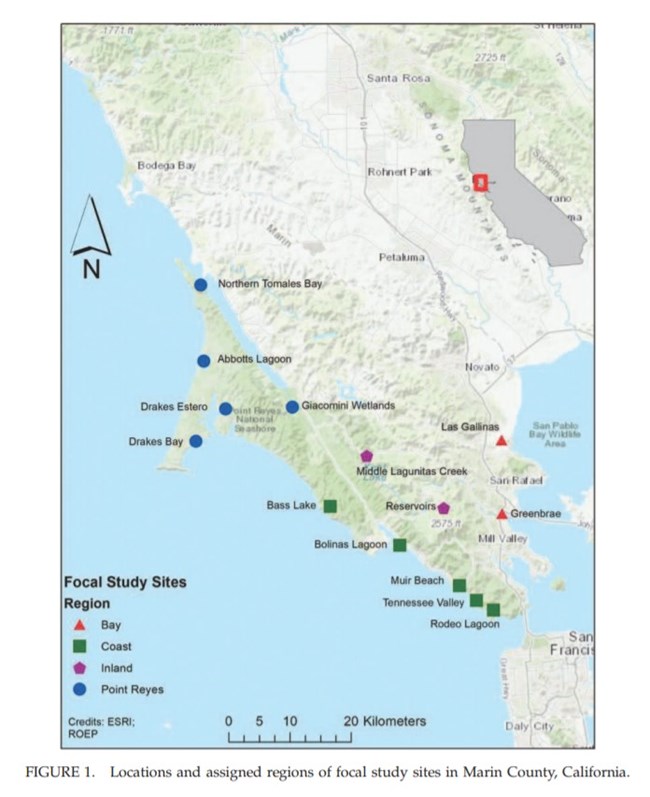

They recently published results from the first five years of their long-term monitoring effort in Northwestern Naturalist. The scientists worked with otter spotters and a network of camera traps to monitor otter populations. "We're interested in how their numbers change in different locations and why there are differences" said Terence Carroll, co-founder and president of the River Otter Ecology Project. Of factors including human impact, ecosystem type, and geographic area, they found latitude was the most significant predictor of otter abundance. Otter populations further north had both higher initial otter numbers and a lower likelihood of being in decline. Carroll suspects the amount and type of foraging area is a predominant factor. Northern Marin County is more likely to have shallower, flatter water and shorelines than the steeper coastal areas in southern Marin.

Otters are ecosystem-health indicators, as both they and their prey are susceptible to poor water quality, pollution, and habitat loss. "Otters use the entire watershed [..] and they are susceptible to all the hazards that those watersheds could present," said Carroll, "but they also are responsive to all the beneficial things those watersheds present [...] they are a mirror of watershed health as a whole." As such, the authors suggest that parks could consider otter recovery as a metric of success at restoration sites such as Rodeo Valley, Redwood Creek, and the Giacomini Wetlands.

Common otter prey includes fish, crustaceans, snakes, insects, and small mammals. Otters in the Marin Headlands have also expanded their palette to include large birds. For instance, park visitor Walter Kitundu once observed a group of otters pursuing a great blue heron at Rodeo Lagoon. “They submerged as they approached and the large female lunged for the heron which was on alert and managed to jump to safety. I knew these otters had a habit of taking on brown pelicans but this was a surprise.”

Otters may also eat threatened or endangered species such as steelhead trout and coho salmon. Thus, as salmonid restoration and monitoring efforts proceed, otters could factor into park decision-making in other ways. As an example, the study authors suggest that considering otters could be useful when planning something like a release of hatchery-raised fish to supplement local coho populations.

For More Information

- Carroll, T., Hellwig, E., Isadore, M. (2020) An approach for long term monitoring of recovering populations of Nearctic River Otters (Lontra canadensis) in the San Francisco Bay Area, California. Northwestern Natruralist 101(2), 77-91.

- Become an “otter spotter” and check out the sightings map at the River Otter Ecology Project

- See Walter Kitundu’s blog post for more photographs of bird predation by otters