Last updated: May 17, 2021

Article

Tourism and Dinosaurs

Article from the proceedings from Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

Tourism & T. Rex Tracks: Sinclair Oil’s Dinoland and Dinosaur Valley State Park

Jennifer L. CarpenterTexas Parks and Wildlife Department, Historic Sites and Structures Program, Texas State Parks

Abstract

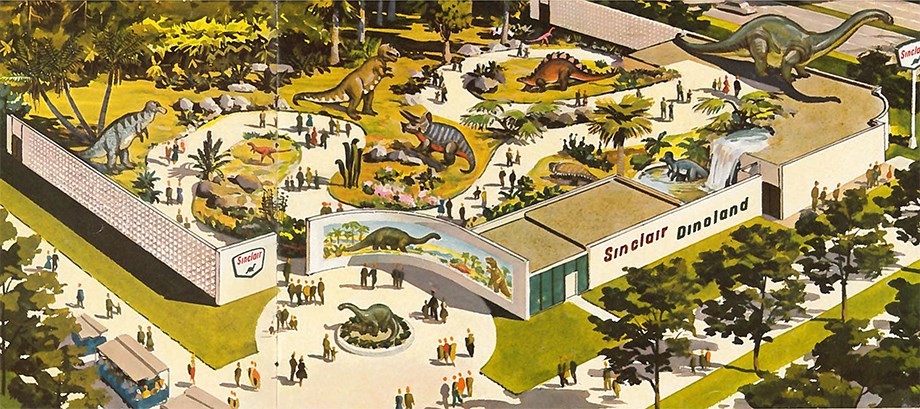

The 1964 New York World’s Fair wowed visitors with dazzling displays of technology and industry promising a bright future. Yet one of its most popular attractions was Sinclair Oil’s Dinoland, a life-size display of ancient reptiles. Inspired by the company’s well-known green brontosaurus logo, men, women, and children by the thousands visited Dinoland.

A public fascination with dinosaurs has spurred countless roadside attractions featuring evidence of the creatures throughout the United States. The discovery of fossilized tracks on private land near Glen Rose, Texas, in the early 20th century captivated local imaginations. During the Good Roads Movement of the 1920s, intrepid out-of-towners hunted for the tracks in riverbeds and overgrown foliage. Scientific study came with the New Deal, when a statewide Work Projects Administration paleontology survey sponsored excavation for museum exhibits. A desire for tourist dollars helped ensure the dinosaur tracks received protection and remained publicly accessible, ultimately resulting in the creation of Dinosaur Valley State Park in 1968.

Shortly thereafter, a merger between Sinclair Oil and the Atlantic Richfield Company retired the former’s famous trademark, an act that presented Glen Rose with a unique opportunity. Local officials, recalling Dinoland’s post-World’s Fair national tour, wished to acquire the dinosaurs for their new state park. Texas Governor Preston Smith helped secure a Tyrannosaurus rex and Brontosaurus; the pair arrived via a 40-foot-long trailer truck in July 1970.

It is rather fitting that two dinosaurs purchased with oil money welcome motoring tourists to Dinosaur Valley State Park. Yet Rex and Bronto, Texas State Parks’ most anomalous “residents,” pose significant preservation and interpretive challenges: the maintenance of life-size ancient beasts now historic in their own right, the juxtaposition of scientific inquiry along roadside kitsch, and the continuing debate between evolution and creationism.

Jennifer L. Carpenter

“Drive with Care and Buy Sinclair”

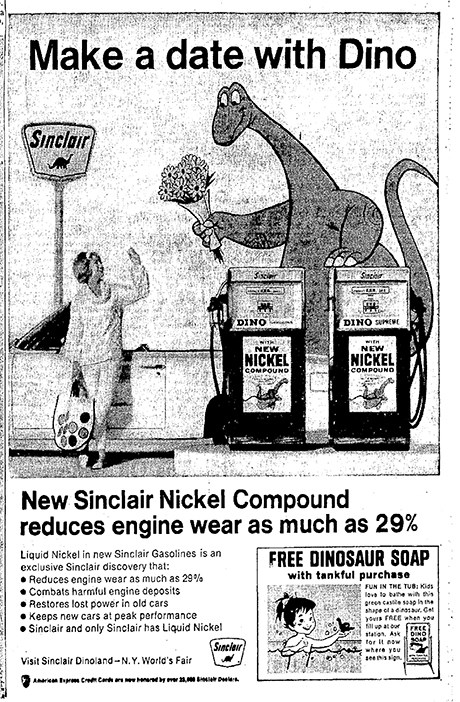

Visitors parking their cars at the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair could likely recite the Sinclair Oil slogan. The company, founded in 1916 by Harry F. Sinclair following a successful investment in Oklahoma’s early oil boom, owned thousands of gas stations across the United States, each adorned with a green brontosaurs logo. Sinclair trademarked its reptilian symbol in 1932 after an advertising campaign featuring multiple dinosaur species revealed the brontosaurus’s popularity among customers. “Dino” quickly became the face of the company’s marketing efforts. [1] If, for some reason, a World’s Fair-goer had not yet “Ma[d]e a Date With Dino” and fueled up the Sinclair way, he or she would be able to do so upon exit at one of two special service stations erected in the Fair’s parking lot.[2]

Corpus-Christi Times Caller, June 8, 1965

What these World’s Fair visitors may not have known, however, was exactly “Why Sinclair is interested in Dinosaurs.” The company’s contribution to the international extravaganza was Dinoland, a 34,418-square-foot “realistic and authentic Re-creation of Life-size Dinosaurs and the prehistoric world in which they lived.”[3] According to Sinclair, dinosaurs “dramatize[d] the age and quality of the crude oils from which Sinclair Petroleum Products are made—crudes which were mellowing in the earth millions of years ago when the Dinosaurs lived.”[4] In other words, a dinosaur mascot was a natural choice for a fossil fuel business, as it reminded customers of the precious resource powering their cars. A less altruistic reason was, perhaps, the logo’s appeal to children, who would beg their parents to stop at the gas station with the giant-but-gentle mascot.

Today, at Dinosaur Valley State Park in Glen Rose, Texas, excited children implore their parents to let them visit the park’s own reptilian residents, Bronto and Rex, before continuing on to view fossilized tracks in the riverbed. What these 21st-century families may not realize is that the two dinosaurs greeting them in Glen Rose welcomed New York World’s Fair visitors 50-plus years earlier. How did two oversized reptiles, artifacts from one of the United States’ most significant cultural events of the mid-20th century, end up in one of Texas’s smallest counties?

New York World’s Fair, 1964-1965

Encompassing 646 acres of Flushing-Meadows Corona Park in the borough of Queens, the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair introduced visitors to new world cultures, foods (most memorably, the Belgian waffle), and high-tech innovations in the spirit of “Peace Through Understanding.” The same site had hosted “The World of Tomorrow,” the 1939-1940 World’s Fair, during the difficult days of the Great Depression. But the city’s second international spectacular would be unlike its predecessor, and indeed, unlike all previous global expositions. Headed by New York’s “Master Builder” Robert Moses, the event lacked an official Bureau of International Exhibitions (BIE) endorsement, which led several leading nations to decline invitations to participate. Instead, Moses turned to American corporations to fill exhibit pavilions and foot the bills. They responded in force.

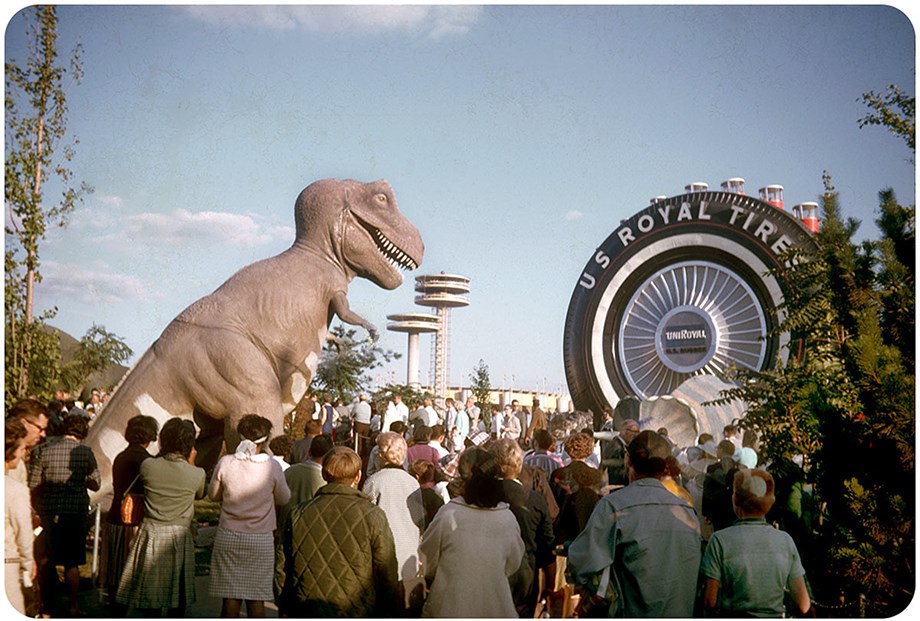

Steve Fasnacht, flickr.com/electrospark

Companies such as Ford, Kodak, and RCA spent thousands of dollars on exhibits, rides, and activities to showcase their latest, cutting-edge products. The Space Age was in full swing, and Fair-goers waited in long lines to take in dazzling displays of technology and industry promising a bright future. General Motors’ “Futurama” exhibit forecasted gleaming modern metropolises (just as their World of Tomorrow exhibit had 25 years earlier), Bell Telephone introduced a video conferencing prototype “Picturephone,” IBM showcased “thinking” computers that aimed to work like a human brain—and there were jetpacks! DuPont and Owings-Corning’s newest synthetic materials, plastic and fiberglass, allowed more flexibility in architectural and product design. Innovation merged with nostalgia in attractions produced by Walt Disney. Early versions of “It’s a Small World,” sponsored by Pepsi-Cola, and a lifelike, speaking Abraham Lincoln for the State of Illinois pavilion helped Disney perfect his “animatronic” technology.[5]

Juxtaposed against the science of the future was a science about the past: paleontology. Situated in the Fair’s “Transportation Area,” sandwiched between the Lowenbrau Beer Garden and the U.S. Rubber/Royal Tires Ferris Wheel,[6] was one of the fair’s most popular attractions: Sinclair Oil’s Dinoland. Inspired by the company’s recognizable brontosaurus logo, this life-size display of ancient reptiles in antediluvian settings captured the imaginations of kids and adults alike. Fair-goers came face-to-face with ferocious beasts of the past! They learned the difference between carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs, the location in the United States where these prehistoric reptiles once roamed, and the meaning behind their Latin names. The exhibit also allowed Sinclair to tout its geological expertise and multi-million dollar research facilities, which, the company hoped, would make visitors of driving age more inclined to purchase Sinclair Oil products for their cars.

The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair was not the first to display life-size dinosaurs. London’s 1852 Crystal Palace Exposition featured a reconstructed dinosaur model. Sinclair’s reptiles debuted at the Chicago’s World Fair of 1933-1934, travelled to Dallas for the 1936 Texas Centennial, and were a popular attraction at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair. A new, updated set was desired for the 1964 event, better reflective of the latest in paleontological research, with some models incorporating moving elements for added believability.[7] Crafting one life-size dinosaur would be a challenging commission for any sculptor, but Sinclair ordered nine for its exhibit—a Tyrannosaurs rex, Brontosaurus, Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Corythosaurus, Anklylosaurus, Struthiomimus, Trachodon, and Ornitholestes. The company turned to a seasoned sculptor to ensure its primordial creatures would impress the general public and professional scientists.

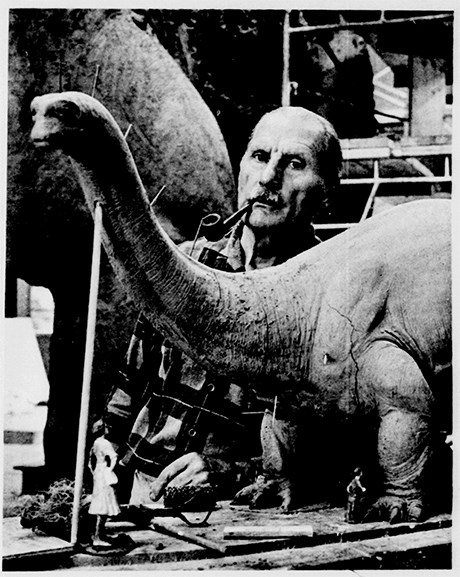

Louis Paul Jonas, Master Wildlife Sculptor

Dinoland featured the work of Louis Paul Jonas, a Hungarian-born taxidermist and sculptor who was known for his meticulous attention to scientifically-correct detail. Jonas immigrated to the United States in 1906 to work with his brothers in a Colorado taxidermy shop. At age 18, while on a trip to New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, he met famed taxidermist, sculptor, biologist, and conservationist Carl Akeley, and became his assistant.[8] Jonas later launched his own business, mounting trophies for big game hunters, but he continued to use his skills for educational purposes. From an abandoned-railroad-station-turned-studio in Mahopac, New York, Jonas built large-scale habitat groups and wildlife displays for museums, as well as small animal figurines. It mattered little whether Jonas had actually seen the animal in the wild. A 1942 magazine article marveled at his ability to learn: “Jonas had never seen a panda, got it up entirely from books, bones, and skin.”[9] Jonas similarly tackled large subjects, such as elephants, with gusto.

Berkshire Eagle, August 18, 1962

By the time of the World’s Fair, Jonas’s decades of experience made him the top choice for the Sinclair Oil assignment. True to form, Jonas wanted to get it right, working with renowned paleontologists Barnum Brown, credited with discovering the Tyrannosaurus rex, and John Ostrom, curator of vertebrate paleontology at Yale University’s Peabody Museum. “No task is too large for the Jonas crew to handle,” proclaimed The Rotarian magazine in 1960,[10] but it took three years and 15+ assistants to complete this prehistoric commission.[11]

Sinclair Oil website, www.sinclairoil.com/dino-history

Working out of a bigger studio in Claverack, N.Y., the Jonas team sketched each dinosaur before crafting 1/10th scale clay models. Transparencies of the models were then projected to actual size on a wall. A plywood frame came next, which was wrapped with wire mesh and filled out with burlap and plaster. This basic form was covered with modeling clay to give the dinosaurs their skin and face detail. The clay was cut into large pieces after it dried, and a plaster mold created for each section. A polyester and fiberglass resin was sprayed and painted into the molds to create “shell” pieces, which, once dry, were bolted onto a lightweight steel frame. Seams were smoothed and sanded, followed by a thorough paint job. Jonas’s dinosaurs were more lifelike than their concrete predecessors, as new materials such as fiberglass allowed for subtle touches like skin texture. Still, the sheer size of the sculpted beasts was amazing: Jonas estimated that his Brontosaurus weighed 5,000 pounds.[12]

The Exciting World of Dinosaurs: Sinclair Dinoland, New York World’s Fair, 1964-65

“Everything is guaranteed authentic,” declared an article in The Daily News-Telegram of Sulphur Springs, Texas, “except for one detail—color. Both the Ford [13] and Sinclair dinosaurs are colored according to what scientists believe they actually were, but a Jonas spokesman admitted it’s really guesswork.”[14] Questions over accurate coloring did not dampen enthusiasm for the project. Once Jonas’s team completed its work, 30,000 locals showed up to give the larger-than-life sculptures a proper send-off. From Claverack, the dinosaurs floated 125 miles down the Hudson River on barges, arriving in the New York City harbor to equal fanfare in October 1963.[15] The Dinoland sculptures ranged in size, from the 6-foot-long Orintholestes to the 70-foot-long Brontosaurus. Each was carefully installed in a Mesozoic Era-landscape featuring lush greenery, water features, and a raging volcano. Dinoland merged education and entertainment, using Sinclair’s interest in dinosaurs to demonstrate the company’s commitment to scientific research and to create brand loyalty, both motivated in large part by profit. Architecture and culture critics openly questioned the heavy influence of corporate money at the New York World’s Fair, but to the event’s 50-plus million visitors, the memories created outweighed the commercialism.[16]

At Dinoland, men, women, and children transported themselves back in time, marveled at the scale of a pre-human world, and perhaps, even took a small plastic “Bronto” of their own home as a souvenir.[17] Those who visited the fair as children can still recall their excitement watching their mini Bronto take shape:

My most visceral memory, and it is very strong, is that of the Sinclair dinosaur machine, where you put coins in—I think it was 50 cents—and the green goop came down the pipes and was pressed between two halves of a dinosaur mold, through the glass, right in front of you. Then it came out the bottom like in any vending machine, still slightly warm. The green plastic smell was fabulous. I kept the dinosaur for years, mostly hoping to capture that smell, a cross between “new car” and gasoline.

Anne Yeager, 57, Bronxville, NY [18]

Could there have been any better souvenir from a petroleum company?

Fossilized Footprints: Discovery at Glen Rose

In its “Exciting World of Dinosaurs” Dinoland booklet, Sinclair asserted its scientific and industrial aptitude: “Even before dinosaurs lived, petroleum was forming in the earth during the Paleozoic Era some 230-million or more years ago. Today Sinclair geologists never cease to explore the world in search of long-hidden and precious petroleum crudes. Some Sinclair oil wells are drilled 3 miles deep, or more, to tap these ancient reserves.”[19] Only the latest technology was deployed upon extraction: “Today, Sinclair uses ultra-modern refining techniques to refine and transform these age-old crudes into top-quality Sinclair gasolines, Motor Oils, and other Petroleum Products…”[20]

The company also funded scientific research in the field of paleontology, further reinforcing the link between Sinclair Oil and dinosaurs. Excavations in Wyoming and Colorado in 1934 and 1937 received Sinclair money,[21] but it was one such-funded study in the small agricultural community of Glen Rose, Texas, that helped Roland T. Bird capture the discovery of a lifetime. A field explorer for the American Museum of Natural History and assistant to Barnum Brown, Bird travelled the country looking for fossils and bones for the institution. Acting on a tip he received from a clerk selling dinosaur tracks at store in New Mexico, Bird pointed his car east and arrived in Glen Rose in November 1938. Much to his delight, right in front of the courthouse was a perfectly preserved theropod track:

…my eyes caught sight of something that made me want to shout for joy. There, inserted in a bit of masonry not far from the door, was a large, three-toed dinosaur footprint. Its surface had been turned away from me, and I’d thought for an instant it was the usual fossilised [sic] log or stump one sometimes finds exhibited in places where fossils abound. But as I swung the Buick in to the curb it presented in all its outlines a faithful picture of such a track.It was a beauty, and there was no doubt that it was genuine. It was all of twenty inches of footprint perfection, made by a three-toed carnivore in mud which had faithfully preserved every minute detail. The satisfaction of seeing it was worth my extra miles; it clarified the worst half of an embarrassing problem, and gave promise of other things. A slab of such prints alone would be a fine addition to any museum collection. [22]

Bird inquired as to the track’s origin and learned such things were “long taken for granted in the community.” Glen Rose’s tracks date to the Cretaceous Period, 113 million years ago, when roaming dinosaurs left footprints in calcium-rich mud. The mud hardened and preserved the shape of their feet and claws. Layers of dirt and sediment covered up the tracks, which were slowly revealed by area rivers through millennia of erosion. Though the courthouse track had been extracted in 1933, local boy George Adams discovered tracks in a Paluxy River tributary in 1909. In 1917, Ellis Shuler of Southern Methodist University published “Dinosaur Tracks in the Glen Rose Limestone near Glen Rose, Texas,” in The American Journal of Science. Track hunting was a popular recreational activity, but it required some effort. Texan newlyweds Joe and Laurie Sanders road-tripped from New Braunfels to Glen Rose on their 1929 honeymoon, climbing through barbed wire and wading through tall weeds to snap photos of the gigantic fossilized footprints.[23]

Good Roads for Glen Rose

Glen Rose, county seat of Somervell County forty miles southwest of Fort Worth, is one of the state’s smallest counties at 188 square miles. The area counts two rivers, the Brazos and Paluxy, and three streams among its waterways.[24] Primarily an agricultural community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the town became a health resort in the 1920s thanks to the discovery of artesian mineral wells. Hoping to capitalize on a tourism boom, and in sync with the national Good Roads Movement, the county began to improve its roads and water crossings. Highway 68 received a concrete and steel bridge in 1923. By the time Roland T. Bird arrived, area thoroughfares were “above average” and easily navigable in his trusty Buick.[25]

Paluxy Valley Archives and Genealogy Society and Somervell County Heritage Center

After meeting local farmer and landowner Jim Ryals, Bird asked to see track locations on his property. Ryals did not share Bird’s enthusiasm for Glen Rose’s dinosaurs. Previously, the farmer had cut a few tracks out of the dried riverbed, hoping to sell them for profit, but the amount of work involved did not bear the expected returns. Ryals described to Bird the types of tracks he had over the years, the number and location of which varied depending on what the river decided to expose. Most had been three-toed theropod tracks, like the specimen Bird encountered at the county courthouse. However, Ryals claimed to have seen tracks of a different shape, now buried under deep silt and gravel. As Bird began to investigate, he came across two trails of three-toed tracks, which he hoped to excavate for his museum’s new Jurassic Hall display. But, after digging into a nearby “pothole,” Bird uncovered something even he could not believe: sauropod tracks. These tracks were larger, rounder, and had four toes instead of three. He was beside himself:

It was like uncovering a place where one of the pillars of Hercules might have stood. My emotions could not have been more stirred over a find of dinosaur eggs. It seemed like an hour, but it must have been less than a minute before my shovel grated bottom, and with a little careful sweeping out the thing was clean enough to be defined.[26]

Finding sauropod tracks was a hugely significant event. At the time, paleontologists debated whether such an animal could even move on land, hypothesizing such creatures instead lived in the ocean.[27] Local resident Charlie Moss had uncovered sauropod tracks in 1934, but, since he was not a trained paleontologist, he mistakenly believed they were elephant footprints. Bird’s experience paid off. He quickly made plaster casts of as many prints as he could, shipped them back east, and shared the news with his American Museum of Natural History colleague Barnum Brown and the local media. Word spread quickly through Glen Rose and reached major cities. The Dallas Morning News published an article on the discovery on November 30, 1938.[28]

Bird returned to Texas for additional work in the spring of 1940. This time funded partially by Texas’s State-wide Paleontological Survey, a Work Projects Administration (WPA) project, and partially by Sinclair Oil, he hired a crew of young male workers to build coffer dams and clean mud and silt from exposed tracks. The project generated a lot of interest, with many residents visiting the site to watch the action. For three months, the men exposed more and more dinosaur footprints, experiencing minor setbacks whenever the spring rains washed away days’ worth of excavation. Bird had promised a tracks to a number of institutions: the University of Texas at Austin, Southern Methodist University, Brooklyn College, and the Smithsonian. The slab delivered to Bird’s own museum measured 28 feet long. Satisfied he had secured some of the best fossilized footprints he had ever seen, Bird wrapped up the project in July, though the slab he unearthed for the American Museum of Natural History was not installed for several years.[29]

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

“What will Glen Rose do with its Dinosaur Valley?”

As big city outsiders and professional paleontologists showed up in Glen Rose in search of tracks, locals began to reassess the value of their taken-for-granted resource. Ryals had not charged Bird access to his property, recognizing the scientific information garnered from the work benefited the public good, but other landowners capitalized on the opportunity, charging access to view tracks on their parcels. Some sold fossils they had unearthed to supplement their incomes, at times out of necessity. Vandalism became a concern, too, as word spread about the area’s prehistoric relics. Still, the community wished to promote its dinosaur discoveries by developing track sites into tourist destinations. Such a move would help boost the local economy and reap the benefits of a post-World War II America that now had the time and money to road trip.

Bird’s excavations brought Glen Rose to the American public through magazine articles, museum displays, and paleontological collections. By 1963, travel writer Ed Syers desired the American public come to Glen Rose, for there was nothing else like seeing the tracks in situ:

I’ve seen both Austin’s and New York’s excellent exhibits. At both, you are quite aware that is what they are—exhibits. Not so with these footsteps. You need pretend nothing. You know where you stand and where they walked. It is that knowing and looking that shakes your earth and turns your sky old. What will Glen Rose do with its Dinosaur Valley?[30]

The Somervell County Historical Society and Chamber of Commerce developed a “Dinosaur Trail” for motoring tourists. U.S. Congressman W.R. “Bob” Poage of Waco proposed a national scenic parkway. Such interventions would bring travelers, but they did little to protect the track sites themselves. In May 1966, the Whitaker family took the first step, offering the Chamber of Commerce a purchase option on their 347 acres, with the intent the land be bought by a private entity and donated to the state. The Texas Legislature created Dinosaur Valley State Park the following spring, though it came with no funding. As time on the purchase option nearly ran out, everything fell into place. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) signed a contract for the land on September 27, 1968.[31]

A Dinosaur-sized Donation

By the time Dinosaur Valley State Park became a reality, the New York World’s Fair was four years in the past. Few of its structures were intended to last beyond the extravaganza, though some pavilions and attractions were reassembled in new locations. Dinoland’s exposition neighbor, the U.S. Royal Tire-shaped Ferris wheel, found a new home along a Detroit, Michigan, highway.[32] Hoping to prolong the popularity of its display (and to continue advertising its products), Sinclair took its reptiles on the road. Tyrannosaurus rex, brontosaurs, and their pals toured the nation, setting up in mall parking lots. Families unable to visit the Fair got the chance to witness at least one of its captivating displays. An estimated thirty-five million people in 100 cities welcomed the Sinclair dinosaur exhibit over 1966, 1967, and 1968. [33]

The Sinclair dinosaur tour stopped in San Antonio and Fort Worth, Texas. At the latter event at the Seminary South shopping center in September 1966, the Glen Rose Chamber of Commerce set up an information booth and handed out “Dinosaur Hunting Licenses,” eager to increase visitation to their town and garner support for its proposed state park. Seeing the large lizards in person, Chamber representatives wished to secure them at the end of their national tour, believing they would be a valuable addition to the site. Texas Governor Preston Smith echoed this petition, in written form and on a radio program in February and March 1970, respectively. Smith’s timing proved better. The spring before, a merger between Sinclair Oil and the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) forced the green brontosaurus logo into retirement. Sinclair no longer needed its life-size dinosaurs, and the Governor’s request for the popular prehistoric statues, along with several others, filled ARCO company mailboxes.

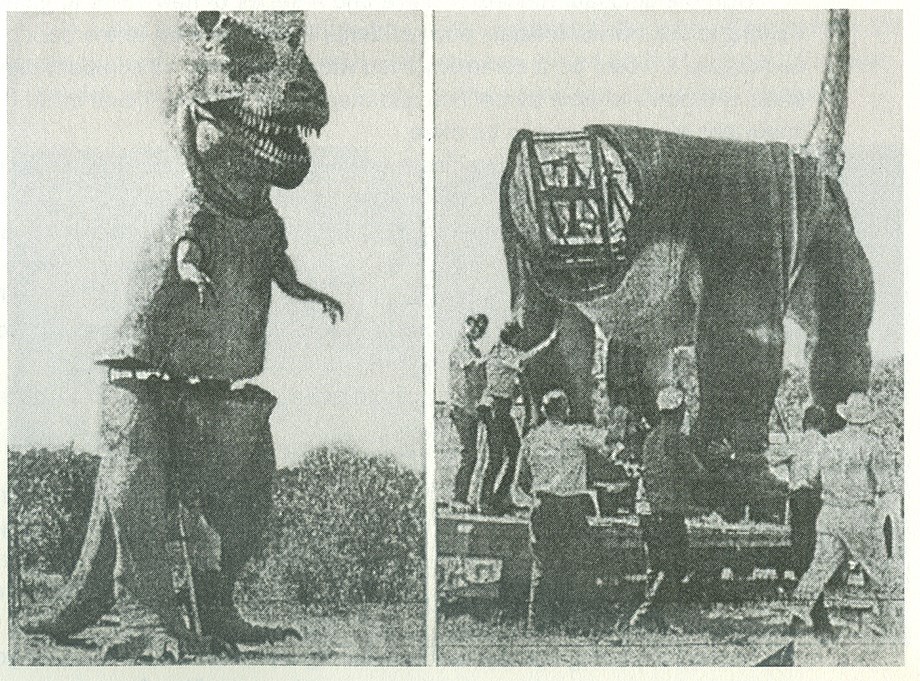

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department officials met with the Governor’s Office in May, where they learned the agency, thanks to Smith’s efforts, would indeed receive two ARCO/Sinclair dinosaurs for its still-in-development park in Glen Rose. Supposedly the oil company promised the entire Dinoland cast to TPWD, but following the deluge of requests, could only promise a partial set. Details came later that summer: “2 full-scale dinosaurs (one Brontosaurus and one Tyrannosaurs rex), one bird, one or two specimens of baby Brontosaurs, and one or two eggs” would arrive at Dinosaur Valley State Park on three tractor trailers. The statues had been mounted to the trailers during their touring days and would need to be cut free. TPWD would also need to supply a hydraulic crane to life them into place.[34]

Eugene Connally Collection, Somervell County Historical Commission Archives

Tuesday, July 14, 1970, marked one of the more interesting days in TPWD history, for it was the day dinosaurs returned to Glen Rose. Dinosaur Valley State Park superintendent Lester Galbreath and staff, having no experience installing such large sculptures, did their best to safely welcome the creatures, but unfortunately, T. rex’s tail cracked when the sculpture’s lower half took an unexpected tumble. Brontosaurus was installed without issue. Sculptor Louis Paul Jonas flew to Glen Rose the next month to repair the tail, surely happy his most-recognized pieces would not go unseen in storage after all.[35] ARCO company representatives were pleased, too. The donation made for a good press release. Frank Sorgorka, the appointed “Father of the Sinclair Dinosaur collection,” wrote:

Our company is very happy to have made the Dinosaurs available to the people of Texas for inclusion in your very fine Dinosaur State Park which is now in the process of completion. We hope that the school children of your great State and the surrounding area will derive educational value and enjoyment out of the exhibit.[36]

Educational, and financially-beneficial, as ARCO could write-off the gift on its tax returns, the company requested from TPWD a formal receipt totaling $94,344.[37]

Dinosaur Valley State Park opened to the public on October 2, 1970. Governor Smith arrived via helicopter to formally accept the ARCO/Sinclair dinosaur models. Roland T. Bird returned to Glen Rose for first time since his dig, the discovery that set everything into motion thirty years earlier. He spent several hours walking along the Paluxy Riverbed reminiscing. The ribbon cutting brought together a diverse group of stakeholders—state officials, oil company executives, paleontologists, local boosters—who gathered with a crowd of 500 in the shadow of park’s two new prehistoric beasts. As for the additional cargo (one baby Bronto, egg, and “bird” (Archaeopteryx)), the park had no place to house them, so the little Bronto went to Oakdale Park in Glen Rose. The egg appears to have been in the possession of TPWD’s Exhibit Shop before becoming part of an exhibit at the University of Wisconsin at Madison’s Geology Museum in November 1976.[38] As of this writing, Archeopteryx’s whereabouts remain unknown. The remainder of Sinclair Oil’s Dinoland figures found new homes in parks, zoos, and other cultural institutions.[39]

During the early days of Dinosaur Valley State Park, its life-size statues, named Rex and Bronto, were the only features greeting visitors on their way to the tracks. Decidedly the most unusual residents of the Texas State Parks system, the pair tested park staff from the beginning with their special maintenance needs. After initially fixing an installation mishap, Louis Paul Jonas Studios returned to Glen Rose in 1974 to complete $10,000 worth of general repairs, including joint realignment and exterior refinishing. Two years later, T. rex’s troublesome tail once again needed work. TPWD staff used “Bondo,” a fiberglass automotive product to repair the damage, but had to guess at the correct paint colors to use, as Jonas Studios had not shared any specifications. By 1984, the brontosaurus tail showed significant deterioration and was missing its tip. Rex had 18 fewer teeth, and both dinos had warping seams and cracks in their skin. This more extensive work totaled $19,150. [40] More recently, Rex received a new coat of paint in 2015, but Bronto’s circa 2010 color has faded, a job estimated to cost $30,000.[41]

Dino-tourism and Creationism

Rex and Bronto are a big draw for the area’s dinosaur-based tourism industry, which in 2012 brought in $23 million. According to Bill Huckaby, former director of the Glen Rose Convention and Visitors Bureau, “The dinosaurs are what drive us. You can’t develop a town of 2,000 into this kind of tourism revenue unless you’ve got something really special to promote.” [42] Mirroring a long-standing public fascination with dinosaurs, the duo are one of countless roadside attractions featuring dinosaurs throughout the United States. Some seek to recreate the thrill of discovery on a paleontological dig. Dinosaur World, also located in Glen Rose, is home to 150 life-size ancient reptiles in outdoor displays. Select ticket prices include an “excavation pass,” a chance for younger visitors to hunt for “dino gems” and fossils, an activity that is not allowed at the state park, in a controlled, pre-stocked pit.[43]

Eric Carpenter

Other dinosaur-themed parks capitalize on a certain kitsch. Virginia’s Dinosaur Land beasts, created around the same time as the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, at times appear weathered, but these dated models delight visitors with fantastic scenes of “dino-on-dino violence.” Bonus displays of other enormous beasts, including a 70-foot-long purple octopus and King Kong, introduce an element of fantasy. [44] Dinosaur Kingdom II, also in Virginia, is even more imaginative. Its outdoor exhibits pit the reptiles against Civil War soldiers in a goofy tale of time travel, mad science, and buried treasure. [45] At Cascade Caverns outside Boerne, Texas, a green T. rex (donated by Walt Disney studios following a movie filming in the area)[46] greets visitors for seemingly little reason other than its novelty. In Texas and beyond, life-size dinosaurs remain an undeniably popular roadside attraction. Even Dinosaur Valley State Park’s beasts share in this appeal, the figures themselves a unique combination of art, advertising, entertainment, education, and nostalgia.

As ready-made photo ops, Rex and Bronto add an element of fun to the park, but scientific analysis of the site’s world-class, priceless prehistoric resources remains an interpretive priority. Static exhibits and ranger-led tours of the tracks teach basic paleontological concepts and emphasize the educational value of the site. Such explanations do not always satisfy visitors’ curiosity, however, as the tracks regularly prompt questions from those whose religious faith offers a different viewpoint. Some proponents of creationism, or intelligent design, assert that dinosaurs and humans lived contemporaneously. Oddly-shaped depressions in local river and creek beds can appear to lend support to such claims, though scientists dispute the idea. The area’s cache of dinosaur tracks attracted Carl Edward Baugh, a self-proclaimed dinosaur “discoverer” and televangelist, who in 1984 founded the Creation Evidence Museum of Texas, located two miles from the state park. [47] The town is also home to “The Promise,” an award-winning outdoor play detailing the life of Jesus Christ in the state’s largest permanent amphitheater. In Glen Rose, entertainment and education, science and religion, two pairs of seemingly contradictory interests, literally exist side-by-side.

No matter your persuasion regarding geological time and the prehistoric era, public perceptions of dinosaurs are derived from figures like Rex and Bronto, who help young and old alike picture a long-ago world. Admittedly, the duo is at best a well-researched and –intentioned projection, but Dinosaur Valley’s unofficial park hosts are more than an Instagram-worthy selfie backdrop. Now over 50 years of age, the dinosaurs are eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Vitally important to the local economy, they attract millions of visitors (and their dollars) to a relatively small-but-growing Texas community and frame discussions about science and faith. It is fitting that two dinosaurs purchased with Sinclair Oil money continue to welcome motoring tourists to Dinosaur Valley State Park, just as they greeted World’s Fair-goers in New York City several decades earlier. Yet Rex and Bronto, Texas State Parks’ most anomalous “residents,” pose significant preservation and interpretive challenges: the maintenance of life-size ancient beasts now historic in their own right, the juxtaposition of roadside kitsch along scientific inquiry, and the continuing debate between evolution and creationism.

Endnotes

- Paleontologists today use the name Apatosaurus instead of Brontosaurus. To avoid confusing the reader when discussing historical events, this paper will use the latter. “Dino, An American Icon,” Sinclair Oil, accessed February 6, 2018, https://www.sinclairoil.com/dino-history

- Lawrence Samuel, The End of Innocence: The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 174.

- The Exciting World of Dinosaurs: Sinclair Dinoland, NewYork World’s Fair, 1964-65. (Sinclair Refining Co., 1964).

- Ibid.

- Samuel, The End of Innocence, 106-110, 169, 179-179, 180-183.

- Liz Robbins, “Recalling a Vision of the Future,” New York Times, April 18, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/interac-tive/2014/04/20/nyregion/worlds-fair-1964-memories. html.

- Three of the nine Dinoland figures (Tyrannosaurus rex, Brontosaurus, and Stegosaurus) had mechanized parts. Brontosaurus had two interchangeable necks, one moving and one static, which were swapped during the winter and summer. All animatronic features were removed from the Bronto and Rex before the pair arrived in Glen Rose, Texas. “Dinosaur Fever – Sinclair’s Icon.” American Oil and Gas Historical Society, accessed January 30, 2018, https://aoghs. org/oil-almanac/sinclair-dinosaur/; “Dino: The Sinclair Oil Dinosaur Fact Sheet,” Sinclair Oil, April 21, 2016, https://www.sinclairoil.com/sites/default/files/Sinclair-Oil-DI-NO-Fact-Sheet.pdf; “Dinosaurs ‘Live Again’ in World’s Fair Show,” The San Antonio Light, April 25, 1965; “Sinclair at nywf64.com, 1964 & 1965 Official Guidebook Entries,” accessed January 15, 2018, http://nywf64.com/sinclair01.shtml.

- Elliott McCleary, “Louis Paul Jonas: He Makes Them Look Alive,” The Rotarian, October 1960, 36-39.

- “Abandoned Railroad Station Is Sculptor Louis Jonas’ Studio,” Life, March 23, 1942, 86-90.

- McCleary, “Louis Paul Jonas: He Makes Them Look Alive,” 36-39.

- Exactly how much Paul earned for his dinosaur models is unclear from available print publications, which state the artist either received a $250,000 commission or secured a $1 million contract. Henry B. Comstock, “Getting There Is Half the Fun,” Popular Science, September 1963, 50-53; John G. Rogers, “Watch Out for Brontosaurus When Driving in Catskills,” The Citizen-Advertiser, August 26, 1963; “Travel Back in Time with Dino - 1960,” Sinclair Oil, accessed January 16, 2018, https://www.sinclairoil.com/history/1960. html; Sinclair Oil, “Dino: The Sinclair Oil Dinosaur Fact Sheet.”

- “Building Dinosaurs for Mammoth Show,” The Berkshire Eagle, August 18, 1962, 8A-9A; Morgan Bulkeley, “Dinosaur Parade,” The Berkshire Eagle, October 10, 1963; Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO), “Louis Paul Jonas, noted wildlife sculptor, created dinosaur group,” July 10, 1970.

- Ford Motor Company’s Walt Disney-designed “Wonder Rotunda” exhibit and “Magic Skyway” ride also featured animatronic dinosaur figures, though visitors viewed them from self-propelled Ford, Mercury, Falcon, Thunderbird, Comet and Lincoln Continental convertibles. The ride drove passengers through time and into “The City of Tomorrow” before releasing them to view the Ford’s latest cre-ations, most notably, the Mustang. “Ford at nywf64, 1964 & 1965 Official Guidebook Entry,” accessed January 15, 2018, http://www.nywf64.com/ford01.shtml; Evan McCausland, “Today in History: 1964 Ford Mustang Debuts,” Automobile, April 17, 2013, http://www.automobilemag.com/news/today-in-history-1964-ford-mustang-debuts-218319/.

- Dick Kleiner, “Dinosaurs, Long Extinct, Make Comeback at Fair,” The Daily News-Telegram, May 12, 1964.

- David W. Dunlap, “World’s Fair Showed a Different Side of the Port Authority.” New York Times, April 16, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/17/nyregion/worlds-fair-brought-out-port-authoritys-whimsical-side.html; “Dinosaurs ‘Live Again’ in World’s Fair Show,” The San Antonio Light; Comstock, “Getting There is Half the Fun;” Bulkeley, “Dinosaur Parade;” Sinclair Oil, “Dino: The Sin-clair Oil Dinosaur Fact Sheet.”

- Joseph Tirella. Tomorrow-Land: The 1964-1965 World’s Fair and the Transformation of America. (Guilford: Lyons Press, 2014), 265, 328; Samuel, The End of Innocence, 88, 123, 198-199.

- “Dinos Popular,” Kannapolis Daily Independent, June, 17, 1965.

- Robbins, “Recalling a Vision of the Future.”

- Sinclair Refining Co., The Exciting World of Dinosaurs.

- Ibid.

- “Dinosaurs ‘Live Again’ in World’s Fair Show,” The San Antonio Light; ARCO, “Louis Paul Jonas, noted wildlife sculptor, created dinosaur group.”

- Roland T. Bird. “Thunder in His Footsteps,” Natural History, May 1939, http://www.naturalhistor ymag.com/picks-from-the-past/241755/thunder-in-his-footsteps.

- Laurie E. Jasinski. Trackways and Memories: A History of Dinosaur Valley State Park. Austin, TX: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, August 2005, 49-50, 56-58, 60.

- Richard Elam, “Somervell County,” Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, modified on February 17, 2016, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/arti-cles/hcs12

- Jasinski, Trackways and Memories, 73-74; Bird, “Thunder in His Footsteps.”

- Bird, “Thunder in His Footsteps.”

- Roland T. Bird. “We Captured a ‘Live’ Brontosaur,” National Geographic, May 1954, 707-721.

- Jasinski, 107-108.

- Ibid., 109, 112-124, 131-132.

- Ibid., 142-143.

- Ibid., 143-144, 146, 157-159.

- “A Royal Legacy,” New York World’s Fair 1964-1965, accessed February 5, 2018, http://nywf64.com/usrub08.sht-ml; Mark Brush, “Here’s what it’s like inside and on top of the Giant Uniroyal Tire,” Michigan Radio, May 22, 2015, http://michiganradio.org/post/heres-what-its-inside-and-top-giant-uniroyal-tire.

- Sinclair Oil, “Travel Back in Time with Dino – 1960;” ARCO, “Louis Paul Jonas, noted wildlife sculptor, created dinosaur group.”

- Memo, Paul Schlimper to Steward Lambert and Johnny Buck, May 15, 1970. Austin: TPWD administrative files; Memo, Jonny Buck to Paul Schlimper, July 7, 1970. Austin: TPWD administrative files.

- Memo, Johnny Buck to W.M. Gosdin, July, 31, 1970. Austin: TPWD administrative files.

- Letter, Frank Sogorka to Otice Green, August 6, 1970. Austin: TPWD administrative files.

- The dinosaur sculptures were valued as follows: Brontosaurs, including one baby and simulated egg, $61,072; T. rex, $32,500; Archaeopteryx $772.

- Letter, Dr. Klaus W. Westphal to Dwight Williford, November 1976. Austin: TPWD administrative files.

- As of this writing, Sinclair’s Dinoland figures reside at the following locations: Triceratops at Museum of Science & Industry in Louisville, Kentucky; Stegosaurus at Dinosaur National Monument in Jensen, Utah; Corythosaurus in Independence, Kansas; Ankylosaurus at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, Texas; Struthiomimus at the Milwaukee Public Museum, Wisconsin; Trachodon at the Brookfield Zoo in Brookfield, Illinois. The Ornitholestes was stolen and never recovered. However, copies from the original mold have been displayed in New Jersey and Calgary, Alberta. Sinclair Oil, “Travel Back in Time with Dino – 1960.”

- Agreement Document for Project Number 354-438, March 20, 1974, Austin: TPWD administrative files; Memo, Billy J. Smith to Robert Hauser, November 4, 1976, Austin: TPWD administrative files; RFQ, “Background and Condition of Dinosaur Models,” and Project Scope Proposal, 1984, Austin: TPWD administrative files.

- Kelby Bridwell, Dinosaur Valley State Park Superintendent, to author via email, February 27, 2018.

- Robyn Ross, “Tracking Creation in Glen Rose,” Texas Observer, April 4, 2012.

- “Pricing Information & Packages,” Dinosaur World, accessed February 5, 2018, https://dinosaurworld.com/texas/ticket-prices.

- “Dinosaur Land,” accessed February 5, 2018, http://dino saurland.com/; “Dinosaur Land,” accessed February 5, 2018, https://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/2234.

- “Dinosaur Kingdom II,” accessed February 5, 2018, https://www.dinosaurkingdomii.com/.

- “Cascade Cavern, Boerne,” published March 13, 2015, https://havingfuninthetexassun.com/2015/03/13/cas-cade-caverns-boerne/.

- “Director’s Bio,” Creation Evidence Museum of Texas, accessed February 5, 2018, http://www.creationevidence.org/about_us/directors_bio.php.