Last updated: August 30, 2021

Article

Tomah Joseph—Passamaquoddy Elder Who Mentored a President

In June of 1934, the 32nd President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, signed the Indian Reorganization Act. This important piece of legislation, which came to be known as the Indian New Deal, set a new precedent for US federal policies that directly impacted Native Americans. Under FDR, the Dawes Act of 1887 was rebuked and abolished, reflecting the administration’s efforts to rectify the ill-treatment and exploitation of tribal communities in previous centuries. During his tenure as the nation’s president, FDR defined himself as an advocate and ally to Native communities and other minority groups and was committed to establishing programs and policies that would seek to benefit tribal governments in their goals for sovereignty and self-determination.

As a national leader, FDR carried with him the relationships and life experiences, particularly in his youth, that informed and inspired his perspectives on human rights. Among the most impactful experiences were those he acquired during his summers at Campobello Island. Like many wealthy families at the turn of the century, the Roosevelts spent summers at seaside resorts. These places provided an escape from city life to destinations with cooler weather and recreational activities. At Campobello, FDR learned to navigate the ocean waters and changing tides taught to him by Tomah Joseph (1837-1914), a Passamaquoddy Tribal Citizen and Native leader. At that time, Joseph was the elected Governor for the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Peter Dana Point (Motahkomikuk). He was renowned as a skilled craftsman and fishing guide, and it was his kindness and expertise that left a huge impact on a young FDR.

FDR's administrative policies were inspired by the Roosevelts and their relationships with local Native communities during their summer getaways. Each summer, in parallel to the migration of the Roosevelts and other wealthy Euro-Americans to Campobello Island, Tomah Joseph would travel down the St. Croix River from his winter home at Motahkomikuk (the Indian Township reservation in eastern Maine) to a summer camp along the Passamaquoddy Bay. This seasonal pilgrimage was one of necessity and tradition. In these wooded areas near Welshpool, Tomah Joseph and his family would collect blueberries, medicinal plants, and sweetgrass for basket-making. For thousands of years, his ancestors had navigated these waterways, following the same routes that had connected them to their traditional homelands throughout what is present-day Maine and New Brunswick Canada. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Passamaquoddy people were treated as wards of the state, many of them subjected to a dependence on government allocations of payments for their timber to survive economically. These government provisions and appropriations were severely inadequate, especially considering how the state continued to benefit from reservation resources, such as land and timber leases, that too often failed to benefit the tribe. To sustain their way of life, Tomah Joseph, like many Native peoples at that time, adopted trademark crafts that honored their history and traditions, while marketing to the wealthy families that vacationed on their traditional homelands.

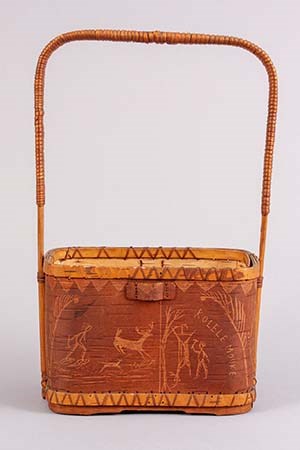

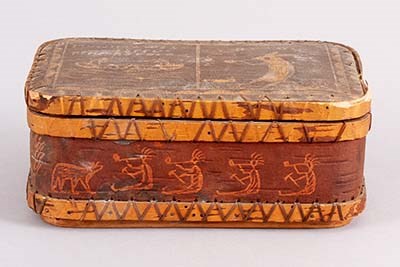

Although their relationship began as an apprenticeship of sorts, Tomah Joseph shared not only his expertise as a master canoeist with young Franklin, but he also shared tales and traditions of his Passamaquoddy heritage. Through the stories of his ancestors, being retold through oral histories and the traditions of wikhegan (picture-writing on birchbark), Tomah Joseph maintained the connection he and his community had to the land and its resources for generations. His skill as a craftsman, through the birchbark baskets and canoes he constructed and decorated, preserved the collective memory of the Passamaquoddy. These illustrations, which included human, animal, and geometric motifs, paid homage to the tribe’s origin stories and lineage. Working with birchbark was a way to remember the Old Time, when the familial Bear, Wolf, Eagle, Raven, and Frog clans emerged.

When the summers ended, the Roosevelts would return to Hyde Park. When the fields began to brown and the grasses died, Tomah Joseph would return to his home in Peter Data Point (Motahkomikuk). The stories and lessons Tomah Joseph shared as he and Franklin paddled around Campobello and the surrounding Islands, however, would have a lasting impact on the future president. After rising to the role of the nation’s leader, FDR enacted governmental policies that restored millions of acres of land to the descendants of the nation’s first peoples. While the Indian New Deal may have been limited in its success in land reparations that would support Native communities in achieving autonomy from the federal government, FDR’s administrative actions were an important step in changing government policies that impacted Native American government, education, employment, property ownership, and self-determination.

Today, the Passamaquoddy community is comprised of over 3,700 citizens that reside between three distinct self-governing units in Pleasant Point (Sipayik), Indian Township (Motahkomikuk), and St. Andrews (Qonasqamkuk) in New Brunswick. They are resilient and persistent peoples who continue to rise above the centuries of institutional genocidal practices by the federal governments of Canada and the United States to assimilate and erase their millennial ties to the land.

Today, we can celebrate the unique relationship between Tomah Joseph, the Passamaquoddy communities, and the Roosevelt family—and the impact that a Native leader, fishing guide, and craftsman—had on one of our nation’s most important leaders. When you visit the home of FDR, you will see the craftsmanship of Tomah Joseph illustrating the traditions of the Passamaquoddy people. These baskets, which combine the tradition of birchbark basket-making with adapted designs inspired by Victorian styles, are testaments to the resilience and survivance of our country’s Native peoples.

This article was prepared by Lexie Lowe, Community Volunteer Ambassador, Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site.

Learn More

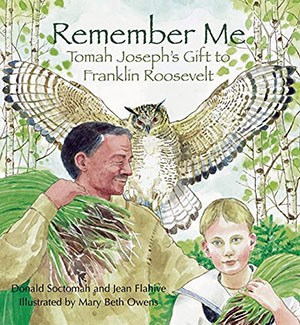

In Remember Me, by Donald Soctomah and Jean Flahive, readers learn how Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the man who would become the thirty-second president of the United States, joyfully spent his boyhood summers on Campobello Island. There he met Tomah Joseph, a Passamaquoddy elder and former chief who made his living as a guide, birchbark canoe builder, and basket-maker. Authors Soctomah and Flahive imagine the relationship that developed between these two as Tomah Joseph taught young Franklin how to canoe and shared some of the stories and culture of his people.

Available wherever books are sold.