Last updated: July 14, 2025

Article

To Honor Him is to Honor Ourselves: How St. Louis Became the First City to Memorialize Ulysses S. Grant

Campbell House Museum.

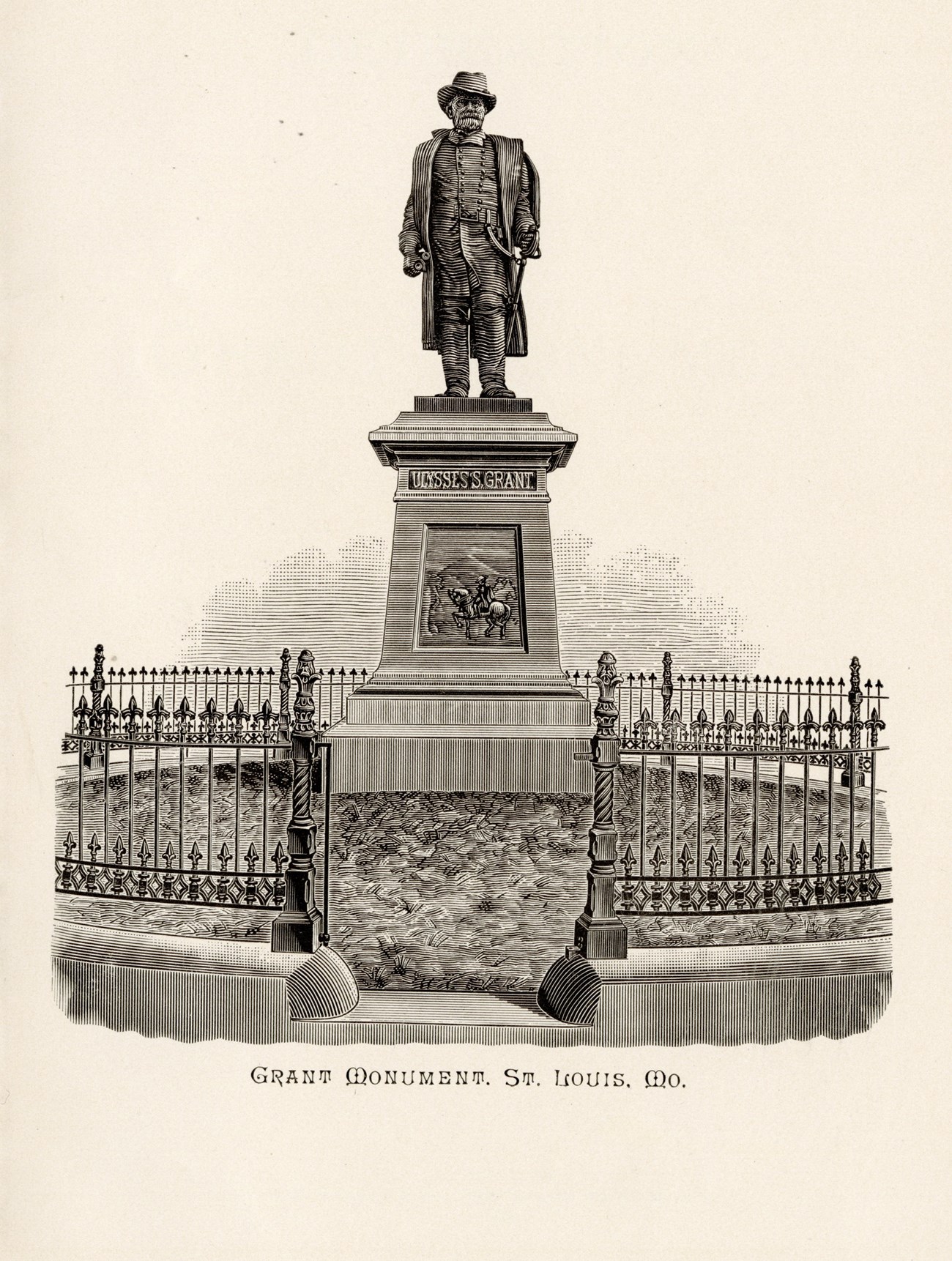

At the southwest corner of Market and Tucker in downtown St. Louis stands one of the city's oldest surviving public monuments, a bronze statue of General Ulysses S. Grant. Sculpted by Robert Porter Bringhurst, the first professional sculptor to reside in St. Louis, the statue was dedicated in 1888 and remains a testament to the city’s desire to lay claim to Grant’s memory. Long before New York or Washington D.C. took formal steps to honor the Civil War general and former president, St. Louis launched a swift and vocal campaign to preserve his legacy. This is the story of how, and why, St. Louis became the first city to build a monument for Grant.

Though Grant was born in Ohio and was living in Galena, Illinois, at the start of the Civil War, many in St. Louis regarded him as one of their own. He began his military career at Jefferson Barracks, just south of the city, in 1843. After resigning from the army in 1854, he lived in the area for six years with his wife, Julia Dent Grant, and her family. During that time, he worked various jobs and struggled financially, farming land near St. Louis at White Haven, which was owned by his wife's family, and hauling firewood into the city. Residents saw him not only as a national figure but as someone whose formative struggles and family life were tied to their own streets and neighborhoods.

This belief that "Grant belonged to St. Louis more than to any other city in the Union" became a local refrain after his death in 1885. Newspapers and residents alike saw Grant as a man who had carried the spirit of the region onto the national stage. As the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted, Grant's character, marked by modesty, discipline, and resolve, reflected Missouri’s self-image in the postbellum era.

One reason St. Louisans felt so connected to Grant was the widely held belief that his greatness extended far beyond military skill. Grant was seen as a man of humility and compassion. An interview with Mary Robinson, a formerly enslaved woman who had worked in the Dent household and knew Grant personally, offered a powerful testimony to this side of his character. Robinson described Grant not only as kind and respectful but as someone who treated her and other enslaved people with basic human dignity, an unusual stance for a white man in Missouri during that time. When asked what she thought of Grant, she said simply, “He was a good man, always.”

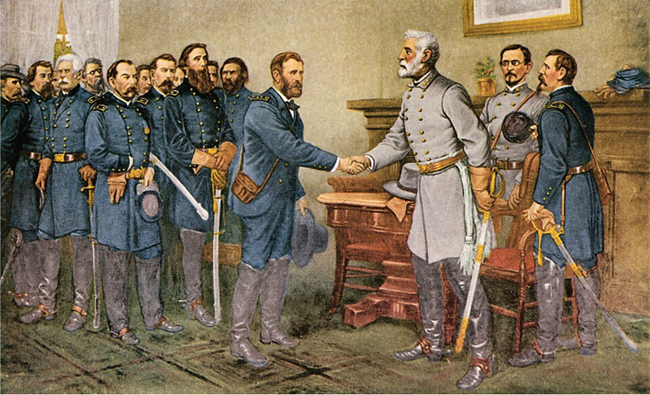

Her words resemble broader national memories of Grant’s conduct, particularly at the surrender at Appomattox. In a historic act of generosity, Grant allowed Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s officers to keep their sidearms, and all soldiers were permitted to retain their horses and personal property. Rather than sending them to prison camps, he arranged for parole and issued rations to the starving troops. This act of kindness stunned many on both sides and helped lay the groundwork for national reconciliation. As one St. Louis resident remarked at the time, "Grant’s one predominant idea was to help the suffering… it was always expressed by actions thereafter."

Galena Public Library

The city’s admiration turned into public action after Grant’s death. In July 1885, St. Louis held a massive funeral pageant, with General William T. Sherman recording in his journal that between 25,000 and 35,000 men marched in line. The parade route started on Broadway, moved west on Gratiot to 4th Street, turned north, and eventually continued south to pass a temporary residence in Soulard on Barton Street where Grant lived in late 1859 and early 1860 while working in Saint Louis. The outpouring of grief and public participation signaled a collective investment in Grant's legacy. Shortly afterward, the funeral committee reconstituted itself as the Grant Monument Association of Missouri and launched an ambitious campaign to fund and construct a statue.

The original members of the committee numbered 13, though deaths and absences later reduced active participation to nine. The fundraising campaign initially drew support from all corners of society. Businesses, civic leaders, war veterans, and ordinary citizens contributed to the effort, which ultimately raised $26,000, well short of the estimated $60,000 budget. However, within a few years the total checks and pledges eventually added up to about $70,000. This would be roughly $1,750,000 today when adjusted for inflation. St. Louis, thriving economically at the time, had the financial momentum and civic pride to sustain such a large commemorative effort. Fundraising was conducted through appeals in newspapers, civic meetings, and public events. Competition with New York and Washington, D.C., added urgency. Many in St. Louis believed that a tribute to Grant would be more meaningful in the city where he had lived and struggled. One local, Joe Carr, declared, "No monument in New York City for me. St. Louis is entitled to the honor more than any other city."

Prominent figures spearheaded the campaign, including Mayor David R. Francis, businessman George D. Reynolds, and General Sherman, who had a deep personal connection to Grant, having served with him throughout the war. He endorsed the selection of Bringhurst, writing: "I promptly ratify the bargain made with the artist Bringhurst... The only suggestion I have is not to make it too stiff."

Sherman advocated for placing the statue at the entrance to Forest Park, opposite Frank Blair’s statue, to create a symbolic gateway. He noted that statues in the city center suffered from smoke and grime, making parks more suitable for public art. Ultimately, five committee members voted for a central location at 12th and Olive Streets, while four favored Sherman’s preferred park setting. The statue was erected at 12th and Olive in Washington Park and unveiled in May 1888. Though Sherman supported the project, he could not attend the unveiling due to prior obligations. He later wrote, "You would not reproach me for not coming to St. Louis for the unveiling... you had plenty of good men to do the work without my traveling a thousand miles and back."

Robert Porter Bringhurst, the sculptor commissioned for the monument, was a fitting choice for the project. His interest in sculpture began in childhood, when he took a job in the marble industry to support his family. He quickly became a skilled carver and later studied and taught at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts, now part of Washington University. Bringhurst also trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he refined a classical style rooted in poetic realism and modeling from life. He returned to St. Louis as the city’s first professional sculptor and went on to leave a lasting impact on its public art. In addition to the Grant monument, his works include the bas-relief "The Coming of St. Louis" and a striking sculpture of Joan of Arc. Bringhurst’s attention to lifelike detail, and his emotional subtlety, helped shape how Grant would be remembered for generations.

Saint Louis Art Museum

The Grant Monument cast in bronze and mounted on a granite pedestal, portrays Ulysses S. Grant standing in full military uniform, holding a sword in one hand and binoculars in the other, his gaze fixed in a moment of calm resolve. Measuring almost ten feet tall, the figure emphasizes Grant’s composed leadership rather than battlefield aggression. A bronze relief on the pedestal depicts the Battle of Lookout Mountain, further rooting the monument in Grant’s Civil War legacy. Bringhurst’s careful attention to realism and historical detail shaped how generations of St. Louisans would come to remember Grant, not just as a general, but as a figure of humble strength and national unity.

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site Collections

The statue was first placed in Lafayette Park, symbolizing Grant’s known presence in local public spaces like Market Square, where he had once sold firewood. In 1898, the monument was moved to the south entrance of City Hall, which some considered a slight. Members of the Grand Army of the Republic quickly objected. They argued that the south entrance was essentially “the back door” of the building and therefore not a place of honor. After lobbying city officials, they successfully pushed for its relocation in 1915 to the southwest corner of Market and Tucker, a more visible and symbolically central location. That move cost $1,500, a substantial sum at the time. In 1921, the statue was moved a second time to its current location, which is in the same general location but adjusted for better public visibility. Today, the statue endures as a marker of local history, civic identity, and political memory. While less nationally prominent than the U.S. Capitol statue in Washington, D.C., the St. Louis monument was the first large-scale tribute to Grant erected in the country.

Regional Arts Commission

In commemorating Grant, the citizens of St. Louis were also celebrating themselves, their values, their sense of place, and their commitment to a democratic vision of the past. This local commemorative culture reflected broader national debates about memory, identity, and race in post-Civil War America. While Grant was honored for his leadership and perceived compassion, other monuments in the city celebrated Confederate-aligned figures, revealing Missouri’s complicated identity as a border state. One example is the former Confederate Memorial at Forest Park, entitled "Memorial to the Confederate Dead": a granite shaft featuring a high-relief bronze of a Southern family sending a young man to war, topped by the Angel of the Spirit of the Confederacy. The back bears a quote from Robert E. Lee: “We had sacred principles to maintain and rights to defend for which we were duty bound to do our best, even if we perished in the endeavor.” This monument was removed in 2017, highlighting the significance of monuments in reflecting the values cities choose to highlight. The inclusion of Mary Robinson’s testimony in the story of Grant’s monument set it apart in a cultural landscape where the legacy of slavery and the Civil War was often erased. In choosing to honor Grant, St. Louis made a deliberate statement about the values it stood for, and the version of history it sought to preserve.

Further Reading

Grant Monument Association of Missouri Records, Missouri History Museum Archives, St. Louis

1885-08-12 How the Promptness of the Grant Pageant Committee in Forming a Monument Association is Regarded by the People - St. Louis Post-Dispatch

1885-07-24 Grief of the American People Over the Death of the Old Commander - St. Louis Globe Democrat

1885-08-07 Arrangements for the Funeral - St. Louis Globe Democrat

1885-08-12 The Grant Monument - St. Louis Post-Dispatch

1885-08-13 The Grant Monument - St. Louis Post-Dispatch