Last updated: November 28, 2022

Article

To Forever Set Free: The Manumission of Robert Green

NPS

During the Ulysses S. Grant Bicentennial in 2022, a resident from New York contacted Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site about a document from her family records. The resident stated that this document was related to slavery at the White Haven estate. Further research determined that this person’s document is a copy of a historic record, but it was still donated to the park for preservation while work is done to locate the original copy. Previously unknown to park staff, this fascinating document raises more questions than answers about slavery’s operation at White Haven.

On December 28, 1838, “Colonel” Frederick F. Dent, the future father-in-law of Ulysses S. Grant, went to the St. Louis County Courthouse and wrote a manumission paper freeing an enslaved man named Robert Green. Aged twenty-eight years old, Green was to be emancipated and “forever set free” with the stroke of a pen. Like other manumissions from the time, no clear reason for freeing Green was stated in the document. The only possible clue emerges from Colonel Dent, who mentioned that Green, for reasons unknown, was entitled to his freedom “upon arriving at the age of twenty-eight.” To ensure Green’s freedom permanently, Colonel Dent went a step further. He wrote on the back of the document that if Green would “be so unfortunate as to be placed in any situation” where his status as a free person was to be challenged, he would “gratefully oblige” and confirm Green’s freedom to anyone who questioned it.

The motivations for freeing an enslaved person were varied. Some enslavers freed enslaved people for good work and/or a personal belief that the enslaved person was deserving of their freedom. Occasionally, an enslaver would grant freedom through terms written in their will. However, manumissions were sometimes granted for less charitable reasons. Elderly enslaved people with health problems were sometimes manumitted because the enslaver could not or did not want to care for them any longer. State governments discouraged this practice because it meant that “taxpayers [who] were responsible for the needy among the free population” would now care for people who were believed to be the responsibility of the enslaver, according to historian Benjamin Joseph Klebaner.

Enslaved people could not count on manumissions to set them free at a future date. During the 1850 calendar year, only one-twentieth of one percent of the entire enslaved population in the United States was manumitted. Ten Southern slave states required a manumitted person to leave the state, and many free Northern states banned free Black Americans from settling within their borders. Going a step further to promote Black colonization to Africa, Louisiana passed a law in 1852 requiring any manumitted person to leave the United States entirely. Between 1857 and 1860, five states banned manumissions altogether, while four other states only allowed manumissions through an act of the state legislature. These steps were taken as a means of strengthening slavery in the South and cementing Black Americans’ status as chattel property under state law.

Manumissions were more common in Missouri, where there were no laws outlawing manumissions and no requirements for a freed person to leave the state (although they were required to purchase a freedom license that was to be on their person at all times). Slavery continued to grow, however. From 1840 to 1860, Missouri’s enslaved population doubled from 57,000 to 114,000 persons. Only three percent of Missouri’s Black population was free by the time the American Civil War broke out in 1861.

Likewise, Colonel Dent’s freeing of Robert Green did not prevent him from continuing to rely on enslaved laborers to generate wealth and personal comfort for his family. Two years after Green’s manumission, the census recorded Dent as enslaving eighteen individuals. By 1850, that number increased to thirty.

NPS

Other mysteries with this manumission document exist. Charles Ellet, the man from whom Colonel Dent received Robert Green, does not appear in any census records from St. Louis. A separate census record suggests Thomas A. Stanton, one of the witnesses of the manumission, may have been born in Ireland in 1784. While he was not an enslaver himself, he lived in St. Louis and may have known Colonel Dent because he lived in political Ward 1, the same ward where Colonel Dent owned a city residence. And Lewis Dent, another witness, may be in reference to Colonel Dent’s youngest son, who would have been only fifteen years old when this manumission document was signed.

A full transcription of this manumission paper can be seen below. This webpage will be updated if new information comes to light about the individuals connected to this document.

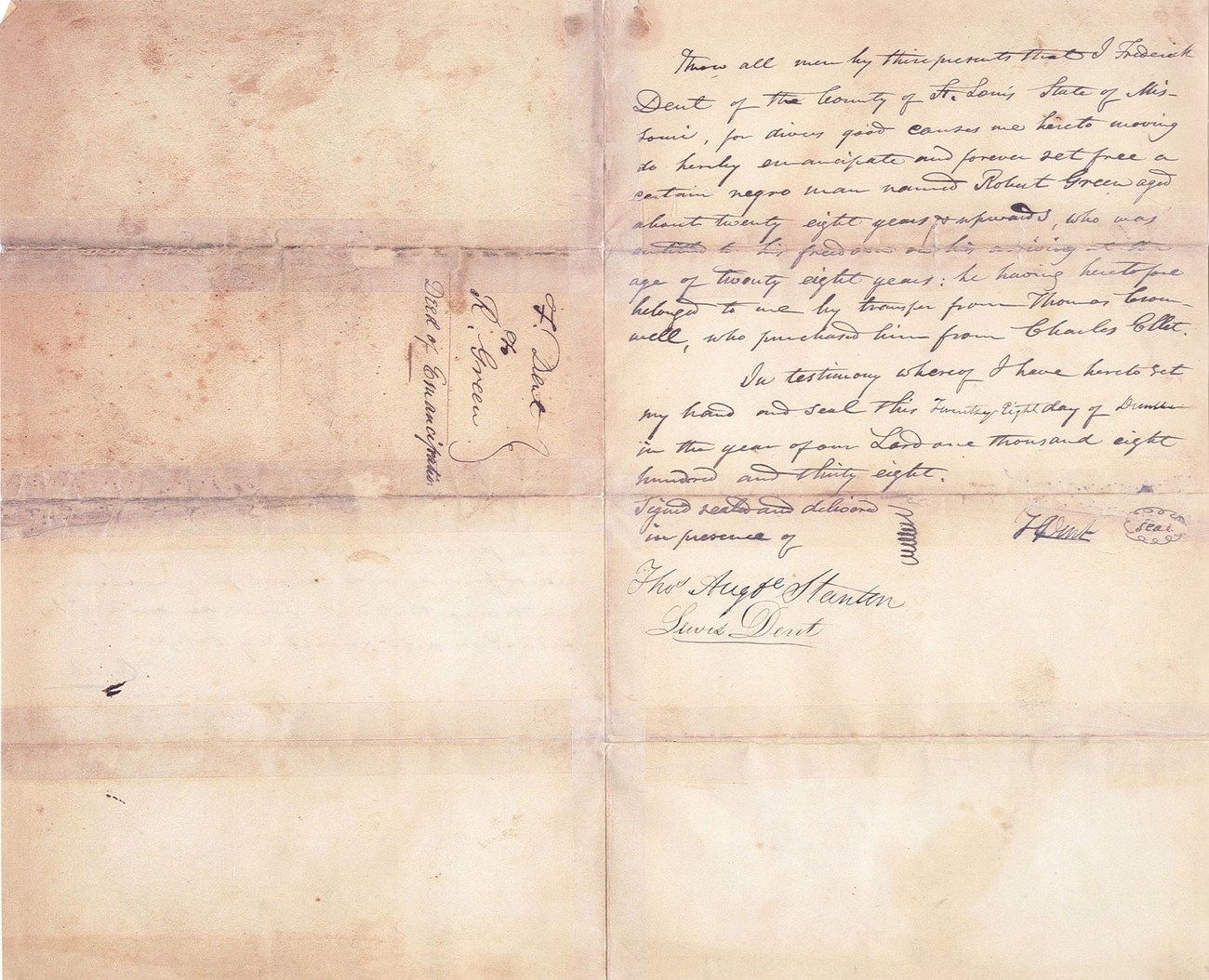

F. Dent

To R. Green

Deed of Emancipation

Know all men by their presence that I Frederick Dent of the County of St. Louis State of Missouri, for diverse good causes me hereto moving do hereby emancipate and forever set free a certain negro man named Robert Green aged about twenty eight years & upwards, who was entitled to his freedom his arriving at the age of twenty-eight years: he, having heretofore belonged to me by transfer from Charles Ellet.

In testimony whereof I have hereto set by my hand and seal this twenty eighth day of December in the year of our Lord one thousand and eight hundred and thirty eight.

Signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of

F. Dent (seal)

Thos. A Stanton

Lewis Dent

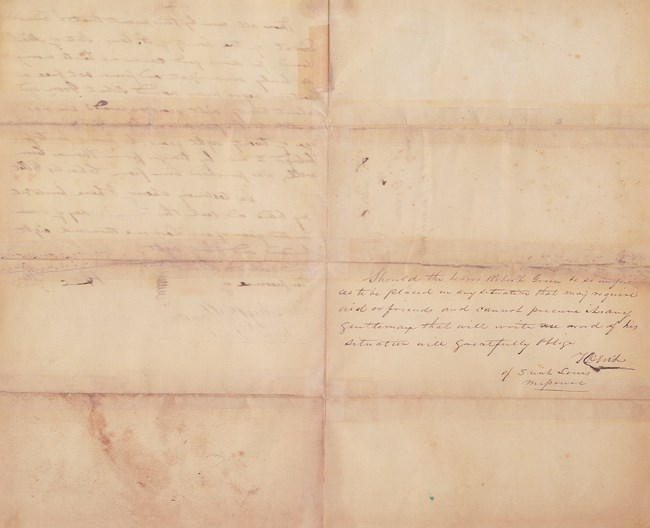

Should the bearer Robert Green be so unfortunate as to be placed in any situation that may require aid or friends and cannot procure any gentleman that will write any word of his situation will gratefully oblige.

F. Dent

of St. Louis Missouri