Last updated: March 6, 2023

Article

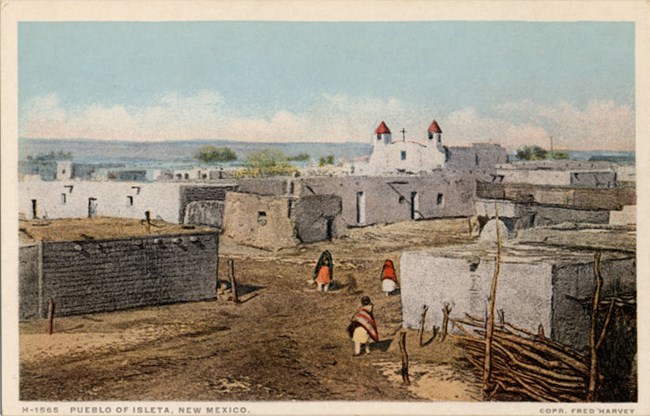

The Tiwa of the Isleta Pueblo Mission

Early Spanish travelers frequently followed an extensive network of Pueblo foot trails that entered mountain passes, followed river valleys, or crossed desert plains to life-supporting water sources. The Spanish Empire colonized New Mexico in 1598, incorporating many ancient Pueblo trails into the Spanish system of wagon roads to colonize the northern frontier. El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, or the Royal Road to the Interior Land, is the oldest and one of the longest wagon routes in North America.

The Camino Real provided a lifeline between the Spanish colonies of northern Mexico and New Mexico. Travelers ventured in caravans, flying flags like sea going vessels, laden with goods, water, and supplies. Camino Real means “Royal Road” or “King’s Highway,” terms applied to official government roads in both Spain and the New World colonies. Archeologists have found many traces of the Camino Real, adding to our understanding of life on the road and cultures during the period.

Tsugwevaga, or the Isleta Pueblo

Pottery fragments dating from the early through mid-1600s show that imports of ceramics to Isleta from other pueblos declined in these years. Archeologists suggest this trend may reflect abandonment of ceramic production centers and disruption of traditional trade among the pueblos under Spanish rule, as well as increasing warfare with neighboring nomadic tribes. Archeological deposits at the Pueblo dating to this period also yield artifacts of Spanish and Mexican influence or origin, along with the bones of farm animals (sheep, goats, pigs, chickens) brought in by the Spanish. Archeologists see in these layers evidence of a “major and rapid collision” of cultures resulting from Spanish exploration and settlement of the region.

On August 10, 1680, the Camino Real turned into an escape route for Spanish settlers and Indigenous allies. Nearly two dozen independent pueblos rose in coordinated rebellion to cast out the Spaniards, marking the beginning of the Pueblo-Spanish War, a desperate struggle for independence that would characterize much of the next two decades in New Mexico. The revolt was a stunning, if temporary, reverse of colonization, but just one of many eruptions of Indigenous discontent during this period.

The Pueblo people overran the Spanish settlements in northern New Mexico quickly. The Lt. Gov. of New Mexico, Alonso Garcia, and 1,500 Spanish survivors gathered at Isleta. Believing that settlers at Santa Fe had been wiped out, Garcia marched his people toward El Paso del Norte, 250 miles down the Rio Grande, and left Isleta to its Puebloan victors.

The original Isleta Pueblo, destroyed by Spanish troops, remained abandoned for over 25 years. Meanwhile, in 1692-1694, the Spanish government regained control over the northern pueblos, successfully employing a mix of military pressure, diplomacy, and in-migration of settlers. Soldiers entering the abandoned Isleta Pueblo during the “Reconquista” noted that the partially burned church and many of the houses were still in good condition. Archeological testing in 2012 revealed a 40-centimeter-thick band of clean sand, blown into the mission compound by wind during the period of abandonment.

Resettling the Isleta Pueblo

Pottery recovered from archeological deposits of the resettlement period reflects a northern frontier Mestizo ceramic tradition, likely brought to Isleta by Tiwa potters from Ysleta del Sur. Tiwas from other areas, along with Hopi and Zuni immigrants, also settled at Isleta and introduced their own preferences in pottery form and decoration. This mix of ceramic traditions is distinctive to Isleta, arising from the pueblo’s multi-cultural resettlement history.

As the southernmost pueblo in New Mexico, Isleta became known as the “Southern Gateway Pueblo” and was frequently mentioned by travelers along the Camino Real. Well into the nineteenth century, travelers moving between Albuquerque and Santa Fe to the north and Mexico City and present-day Ciudad Juárez to the south frequently camped opposite Isleta Pueblo at the West Cat Hills campsite, visiting and trading with the nearby Tiwa.

Fragments of bottle glass were also found in this area, including brown glass, aqua glass, and the older olive-black specimens. Spanish traders or missionaries stopped to camp here, leaving behind the pieces of any bowls, jars, or cooking pots that broke during the journey. Those goods that survived the trip were probably traded with the Tiwa at Isleta for food or other supplies the Spanish needed once they hit the road in the morning.

The Spanish, probably the Franciscan priests operating the missions, introduced the practice to the Pueblos. It it became commonplace throughout the Southwest due to the availability of the raw materials. Isleta Pueblo also traded selenite to the Rio Grande settlements for use in settlers’ windows, and a supply was ordered for the windows of the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe.

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro remained a Spanish colonial trade route until 1821, when Mexico gained its independence from Spain. In that same year, the newly opened Santa Fe Trail began supplying American goods to New Mexico, and often US and Mexican merchants would continue south into Mexico along the old camino. Long distance travel along the Camino ceased in the 1880s when railroads began providing a faster means of transportation.

El Camino Real Today

The Puebloans who resettled Isleta Pueblo reconnected to the ancestral Isleta landscape and traditional culture, and the community today retains a long ancestral memory and oral history of local land use. As passersby come across small bits of ceramics in the dust along the side of the Camino Real, they are reminded that this road once linked these ancient pueblos of New Mexico to a vast global transportation corridor and international trade network.

Sources

Knaut, Andrew L.

1995 The Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Conquest and Resistance in Seventeenth-Century New Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Marshall, Michael P.

2015 Isleta Pueblo and El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail. Cibola Research Consultants Report No. 567. National Trail Intermountain Region, National Park Service.

Marshall, Michael P., Michael Bletzer, and Henry Walt

2017 The Isleta Pueblo: El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail. Crossroads Investigation Project. Isleta Pueblo, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the National Park Service.

Palmer, Gabrielle G.

1993 El Camino Real de Tierro Adentro: The Camino Real Project. Bureau of Land Management. New Mexico State Office. Cultural Resources Series No. 11. Sante Fe, New Mexico.

Staski, Edward

2004 "An Archaeological Survey of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, Las Cruces—El Paso." International Journal of Historical Archaeology, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 231-245.