Last updated: January 28, 2025

Article

Thomas Young

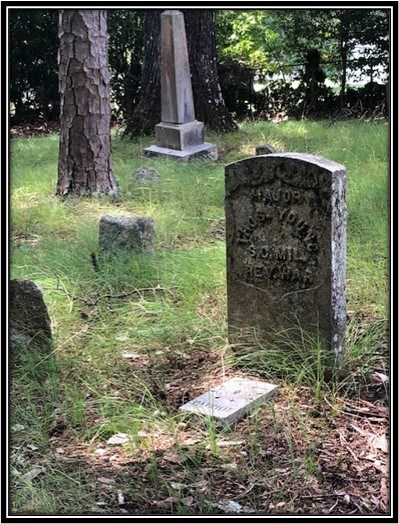

NPS Photo.

Major Thomas Young was born in Laurens District, South Carolina on January 17, 1764. His family relocated to Union District shortly after his birth. Major Young made his living as a farmer. He married twice and after the passing of his first wife, Lettie Hughes, he married Sarah Cunningham. According to one family genealogy, Thomas Young fathered eleven children (i).

Thomas Young was 15 years old when the violence of the American Revolution altered his life. In the wake of the British triumph at Charleston in May of 1780, the civil war amongst the citizens of South Carolina erupted into an appalling new level of violence. Trying to make sense of the violence, General Nathanael Greene wrote to Alexander Hamilton in 1781 saying "the Whigs and Tories persecute each other, with little less than savage fury. There is nothing but murder and devastations in every quarter (ii)." The repressed loyalist population in South Carolina rallied to the King's banners. Tory loyalist militias, backed by the power of the British army, began to reassert control by taking the war to patriot Whig sympathizers. South Carolina Militia Major Joseph McJunkin wrote that “The British are victorious and asserting their zeal for the royal cause; not a single corps of Whigs is known to be embodied in the State; the cause of liberty is desperate (iii)." Seizing the moment and seeking retaliation for the treatment endured during the first phase of the war, Tory militias and British Regulars struck deep into the interior of the South Carolina backcountry. As the civil war intensified, Whigs and Tories lashed out at their friends and neighbors, and the line between civilian and soldier quickly disappeared.

In early June of 1780, Colonel Thomas Brandon and other militia commanders mustered a force of patriots at Fairforest Creek, near present-day Union, South Carolina. Colonel Brandon's men captured a local loyalist informer named Adam Steedham. Major McJunkin referred to Steedham as "a pet Tory (iv)." Steedham either escaped custody or was released and quickly made his way to the camp of loyalist officer William "Bloody Bill" Cunningham where he disclosed the location of Brandon's camp. Cunningham raided Colonel Brandon's camp just after sunrise on June 8, 1780. Among the killed, wounded, and captured at Brandon's Defeat, was John Young (v). Thomas and John Young were brothers and very close in age. (vi) . Adam Steedham fled to Georgia after the Cunningham raid and returned to Union District several months later. Thomas Young was waiting for his return (vii).

In his memoir published in 1843, Thomas Young stated that the murder of his brother was his reason for joining the South Carolina militia. Major Young wrote, "I shall never forget my feeling when told of his death. I do not believe I had ever used an oath before that day, but then I tore open my bosom, and swore that I would never rest till I had avenged his death. Subsequently, a hundred tories felt the weight of my arm for the deed, and around Steedham's neck I fastened the rope as a reward for his cruelties (viii)." After the execution of Steedham, 15-year-old Thomas Young joined Colonel Thomas Brandon and left his youth behind.

Young’s first action was at Stallions' Plantation in 1780. He stayed in Colonel Brandon's company and was in battle at Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780. Young was in a division led by Colonel Benjamin Roebuck. Recalling the victory over British Major Patrick Ferguson and his loyalist army, Young wrote, "Awful indeed was the stench of the wounded, the dying, and the dead on the field, after the carnage of that dreadful day (ix)." Young guarded the prisoners on the march into North Carolina and witnessed the trial and hangings of loyalist prisoners at the Biggerstaff Plantation.

Young returned to South Carolina and joined General Daniel Morgan's Continental and militia army at Grindal Shoals. General Morgan dispatched the 3rd Continental Dragoons under Lieutenant Colonel William Washington, plus, South Carolina mounted troopers to track down and destroy a loyalist force known as the Georgia Horse Rangers (x). In December 1780, William Washington wrote to Nathanael Greene and described the devastation wrought by Thomas Water’s Horse Rangers saying that, “The distress of the Women and Children stripp’d [sic] of everything by plundering Villains cries aloud for redress (xi)." Washington found the group near Hammond’s Store and obliterated the whole of Lieutenant Thomas Water’s Georgia Horse Rangers (xii)." Thomas Young rode into the fight with Colonel Thomas Brandon, Major James McCall, and Major Benjamin Jolly. He emerged unscathed from the decisive victory over the Tories.

Not yet 17 years old, Thomas was a veteran soldier and hardened by the war. He wrote of this disturbing event during the Hammond’s Store campaign, “There was a boy of fourteen or fifteen, a mere lad, who in crossing the Tiger River was ducked [sic] by a blunder of his horse. The men laughed and jeered at him very much, at which he got very mad, and swore that boy or no boy, he would kill a man that day or die. He accomplished the former. I remember very well being highly amused at the little fellow charging round a crib after a Tory, cutting and slashing away with his puny arm, till he brought him down (xiii)." War is harsh and the first casualty is innocence.

On January 17, 1781, Thomas Young was with General Daniel Morgan's army on the battlefield at Cowpens, South Carolina. It was his 17th birthday. He was attached to Major Benjamin Jolly's South Carolina Mounted Militia. Bearing down on Morgan's Army was feared British commander Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton and 1100 of the best British troops in the Southern Colonies. General Morgan had around 1500 troops. At the height of the battle, British infantry charged the American battle line, and Major Jolly's force burst out of the woods. Young wrote "We made a most furious charge, and cutting through the British cavalry, wheeled and charged them in the rear (xiv)." The mounted militia smashed the advance of 50 British Legion Dragoons, drove them from the field, and turned to strike the charging 71st Highlanders in the rear. Caught in a textbook "Double Envelopment", Tarleton's army disintegrated.

The Battle of Cowpens lasted about one-half-hour. Tarleton fled the field with around 200 survivors. The American cavalry pursued the British for twenty miles, and Thomas Young joined in the pursuit. He encountered a British cavalry patrol and tried to outrun his foes, only to be overtaken when his horse gave out. Young wrote "It was a plain case now, and I drew my sword and made battle. I never fought so hard in my life. I knew it was death anyhow, and I resolved to sell my life as dearly as possible (xv)." Alone and outnumbered Young suffered saber wounds to his hand, arm, forehead, right shoulder, left shoulder, and a last slash on the back of the head. In captivity, Young was nearly murdered by a loyalist named Littlefield, who knew him, but was saved by twenty British Dragoons who "drew their swords, and cursing him for a d____d coward, for wanting to kill a boy without arms and a prisoner -- ran him off (xvi)." Young was brought before Banastre Tarleton who he described as a "very fine looking man, with rather a proud bearing, but very gentlemanly in his manners (xvii)." Tarleton questioned Young and asked about Washington's cavalry and mounted state militia at the Cowpens battle and said, " but you know how they won't fight." Tarleton replied "By G_d! They did to-day, though (xviii)!" Tarleton had Young's wounds tended to and promised to parole him when they reached General Cornwallis's camp. Young and another American prisoner escaped later that night when a redcoat, whom the two captives helped hide a stash of loot, looked the other way as they slipped into the darkness.

Hiding out on a farm for several weeks, Young recovered from his Cowpens wounds. He re-joined Colonel Brandon's militia company at the Siege of Fort Motte and the taking of Orangeburg, South Carolina. After those actions, Young joined Captain Boykin for a raid on British horse stables near Bacon's Bridge. Boykin's company disbanded after the raid and Young joined Colonel Brandon and Benjamin Jolly and rode to General Nathanael Greene’s ongoing siege of Ninety Six. After the siege at Ninety Six was lifted by British troops, Young returned to Union District and served as a scout for Colonel Brandon and Major Jolly.

While scouting in Union District, Major Young’s cousin, Tory William Young, offered one-hundred gold guineas for his capture and transport to Ninety Six. The bounty went unpaid.

Thomas Young was captured one final time by “a party of ‘Outliers’…the most notorious and abandoned plunders and murderers of that gloomy period (xix)." One of his captors was previously a prisoner of Major Young’s militia company and because Thomas had treated him well, the man released him unharmed. Young served with the South Carolina militia until the Treaty of Paris was signed in September 1783 and returned home to the family farm.

Major Young Thomas Young died on November 7, 1848, and was laid to rest in the Old Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Monarch, South Carolina (xx)."

i Brown, P. R. (2019, December 22). About Maj. Thomas Brandon Young Jr. Geni.com. Retrieved August 15, 2023, from https://www.geni.com/people/Maj-Thomas-Young-Jr/6000000079424226164 ii Greene, N., General (1994). The Papers of General Nathanael Greene Volume VII 26 December 1780 - March 1781 (p. 88). The University of North Carolina Press. iii Saye, J. H., Rev. (2014, March 14). Memoirs of Major Joseph McJunkin - 1848. Carolinamilitia.com. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from http://www.carolinamilitia.com/memoirs-of-major-joseph-mcjunkin/ iv Ibid, McJunkin. v Ibid, McJunkin. vi Ibid, Brown. vii Parker, Jr, J. C. (2013). Parker's Guide to the American Revolutionary War in South Carolina (2nd ed., p. 424). Infinity Publishing. viii Young, T., Major (2014, March 14). Memoir of Major Thomas Young. Carolinamilitia.com. Retrieved August 15, 2023, from http://www.carolinamilitia.com/memoir-of-major-thomas-young/ ix Ibid, Young. x Murphy, D. (2014). William Washington American Light Dragoon: A Continental Cavalry Leader in the War of Independence (pp. 73-75). Westholme Publishing, LLC. xi Greene, N., General (1991). The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Volume VI 1 June 1780 - December 1780 (p. 611). The University of North Carolina Press. xii Ibid, Murphy pp. 73-75. xiii Ibid, Young. xiv Ibid, Murphy. xv Ibid, Young. xvi Ibid, Young. xvii Ibid Young. xviii Ibid, Young. xix Ibid, Young. xx Ibid, Young

Tags

- cowpens national battlefield

- kings mountain national military park

- ninety six national historic site

- overmountain victory national historic trail

- cowpens

- cowpens national battlefield

- kings mountain national military park

- southern campaign nps

- southern campaign of american revolution

- america 250 nps

- american revolution

- american revolution 250

- american revolutionary war

- thomas young

- patriot

- south carolina

- south carolina history

- america 250