Last updated: July 6, 2024

Article

Their Full Share: Remembering the Revolution

“The people of Upton had paid their full share…”

The Blackstone Valley is known in the annals of United States history for its citizens’ role in launching the American Industrial Revolution. Yet few have paid much attention to the important events that directly preceded this revolution, and the ways that people in this area fought in the War for Independence. Local historians, of course, are exempt from this generalization.

There are numerous reasons why the American Revolution usually comprises a smaller chapter in the history books about this area. The people who lived between the port city of Providence, Rhode Island, and the villages near the headwaters of the Blackstone River during the Revolution were at a remove from many big events during the war. They did not experience the burning of ships, the destruction of tea, the threat of occupation, or the firing of cannons from their own yards. The calls to fight, and the signaling of alarms, came from a great distance in many cases. Yet military records and volumes about various small towns inform us that people throughout the Valley answered those distant calls, not just once, but with regularity.

While some historic sites will serve as magnets for American Revolution history, in other locales, the history we do not yet know will need to be pulled out, and forward, to better shape our understanding. In Upton, Massachusetts, a rural community in the Blackstone River Watershed, we find a history not just of service, but of ordinary people dedicated to considering the cost of the Revolution. For Upton residents, their own town anniversaries usually prompted deeper reflection. From the first generation of heirs to the Revolution, to the mid-20th century, community leaders have chronicled their ancestors’ and predecessors’ sacrifices, calculating what it meant for “the people of Upton” to have “paid their full share.”

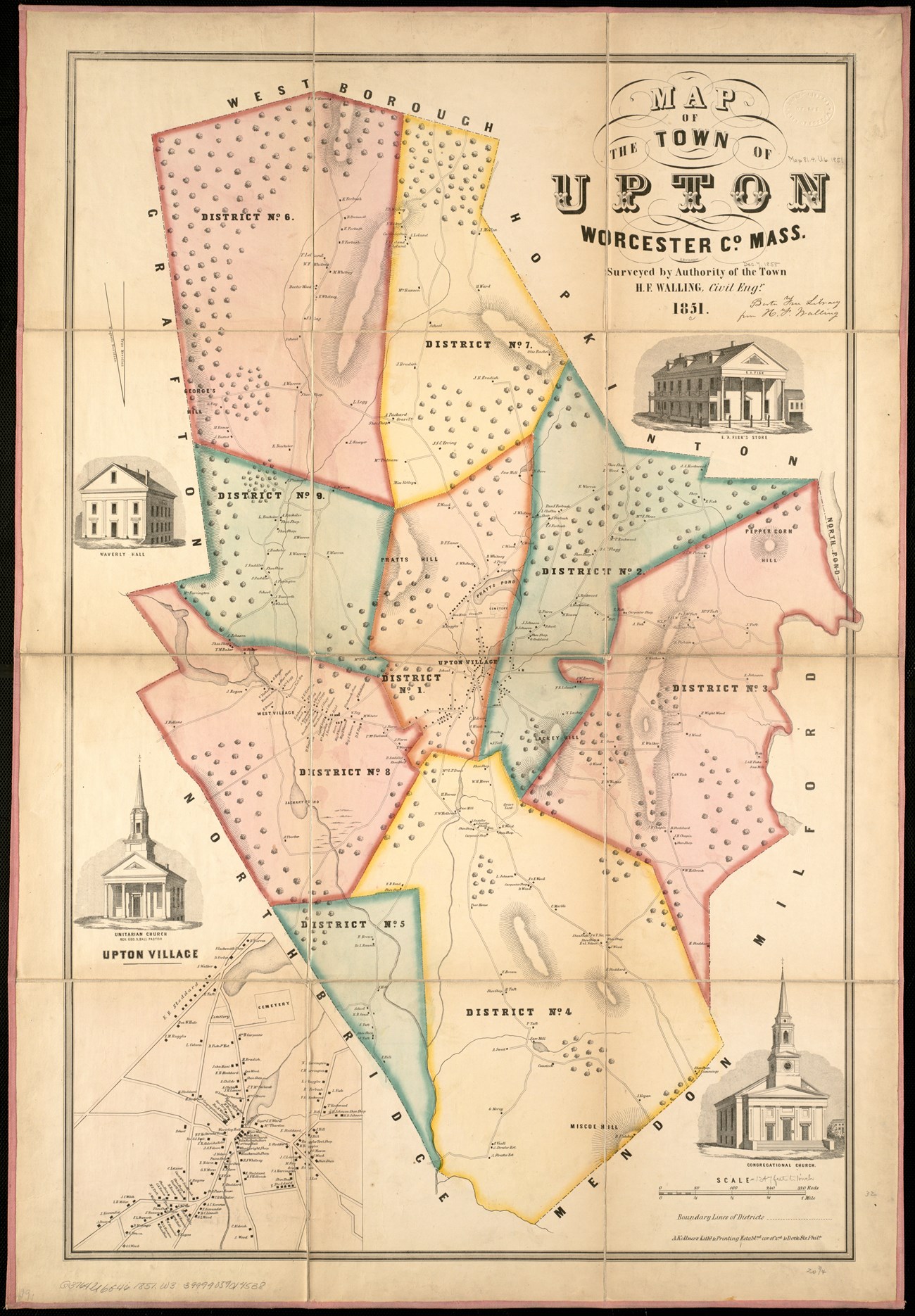

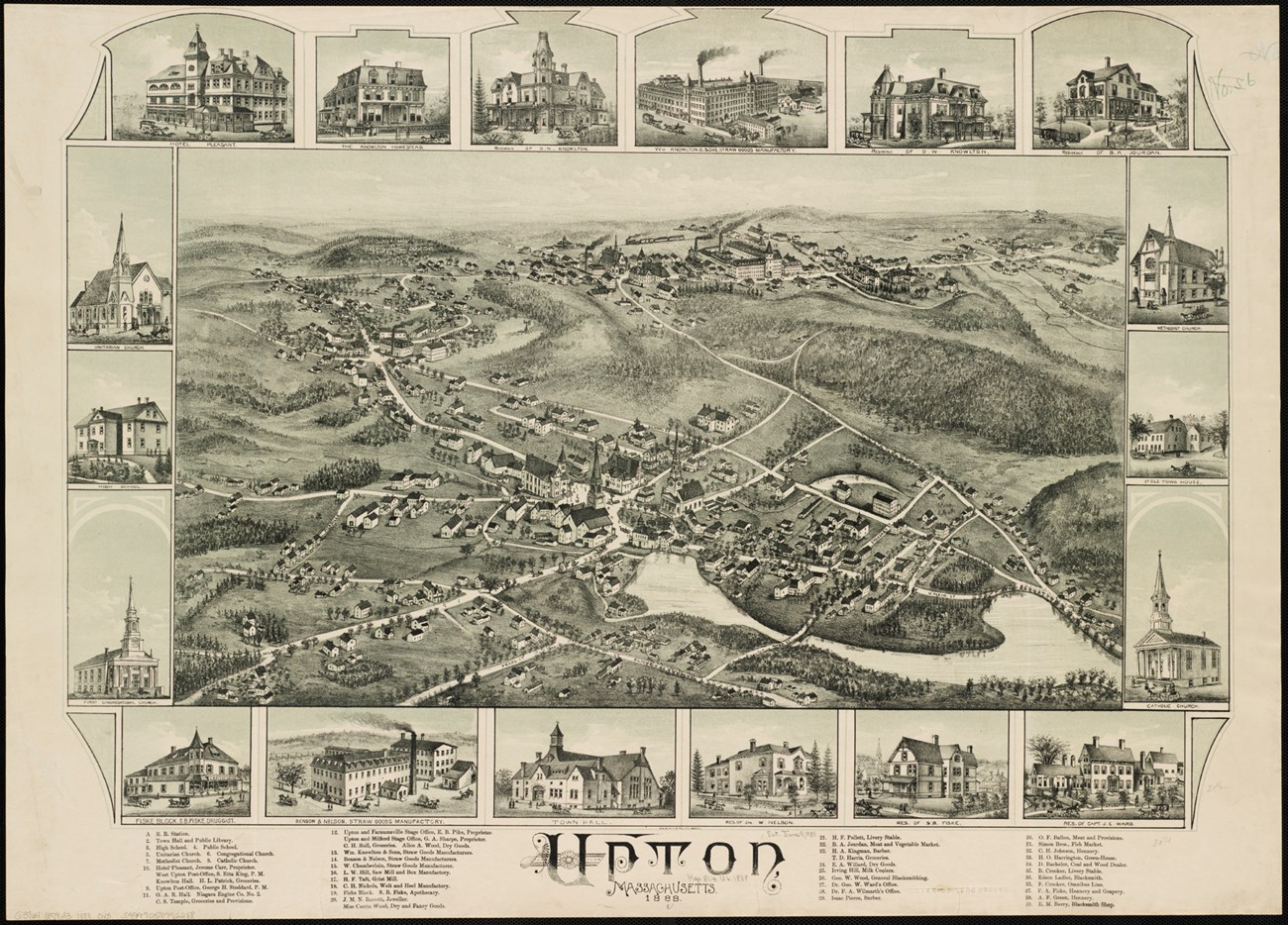

Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

Before the War

Many colonial towns in Massachusetts were cleaved and formed from other communities. Upton was created from land previously under the names of Hopkinton, Mendon, Sutton, and Uxbridge on the homeland of the Nipmuc. Early maps show strange outlines and a curious shape to Upton, which is bounded on one side by the Mill River. The town’s official establishment date, which has been celebrated for decades, is June 14, 1735.

The earliest English colonists who moved west to Upton came from Hopkinton, Westborough, and as far away as Boston. In the 1730s, there were about 50 families living nearby during incorporation. Only half owned their land. In the New England Gazetteer, John Hayward described Upton as full of “plain land” across a landscape that was “partly rough and hilly, with a strong soil capable of yielding good crops of grain and hay.” In the early years, a few hundred farmers tended to their soil and some freemen built up a number of mills.

For most people living in this area—at both the start and the end of the Revolutionary War—industry was a word describing hard work at home. Members of the Nelson family, for instance, did weaving and spinning inside their house; multiple generations worked alongside one another, planning their labors in tandem. Other folks in town took to making cloth with wool, or to spinning flax and even hemp. This was a relatively small, sprawled out community. Even after the Revolution, the population of Upton was still under 1,000. A significant increase in population did not come until the mid-1830s, with the expansion of some small-scale industries.

Signs of Dissent

The people of Upton were far from the great trading centers of their day in colonial North America. Yet they eagerly passed town resolutions showing their resistance to new policies forced on them in the 1770s.

RESOLVED: — That we will treat with contempt all those persons that do continue to import goods from Great Britain contrary to the non-importation agreement. And that we will look upon such men with detestation, who, for the sake of their own private interest, are willing to reduce their posterity and their country to a state of abject slavery.

RESOLVED: — That we will not purchase or drink any foreign teas until the revenues acts are repealed.

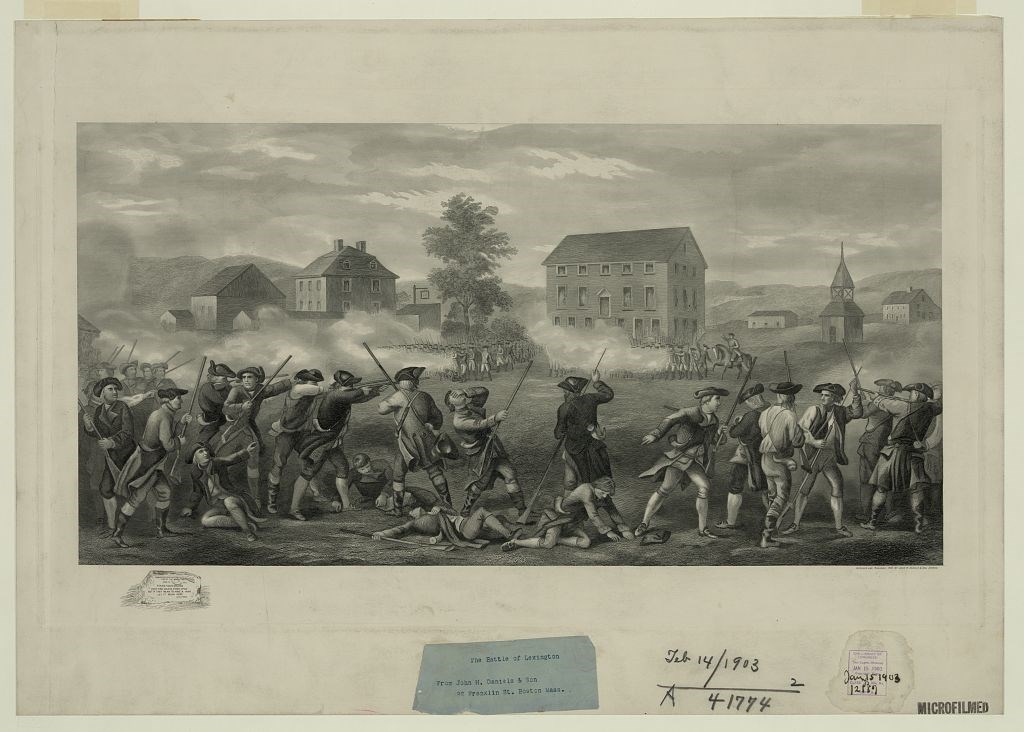

With these resolutions, Upton men made their position clear. From this point forward, what you wore and where you got your drink sent a message about your loyalty to your neighbor or the Crown. When the alarm rang on April 19, 1775, a number of Upton men marched to Roxbury, including Thomas Nelson and Benjamin Potter. On April 30, 1775, Nathan Nelson enlisted and served under Col. Joseph Read. This was his first of many periods of service over the next five years. In 1780, a paper from Captain B. Read explained that “Nelson and others belonging to the town of Upton had supplied themselves with firelocks, etc., while on three months of service.” Benjamin Palmer, a yeoman from Upton, also enlisted, and his service included three years with the Continental Army.

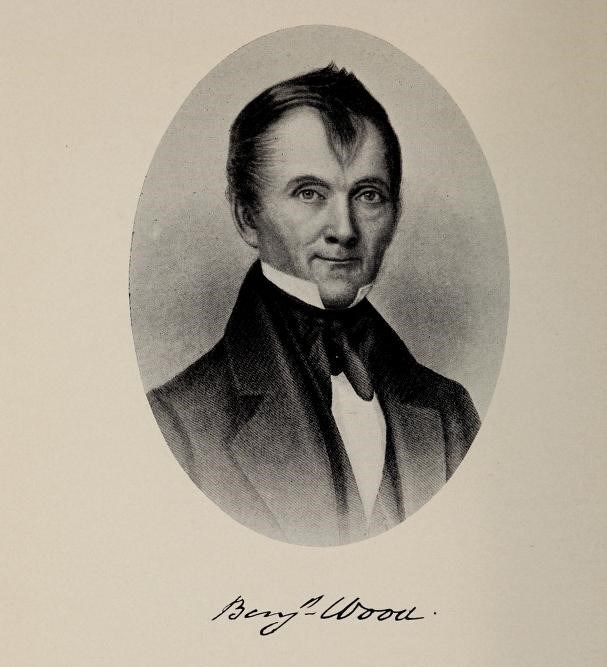

Reverend Wood – 1835

On June 25, 1835, Benjamin Wood, pastor of the Congregational Church in Upton, gave his “Centennial Address,” which was later published in Boston, MA. Wood was born in 1772 in New Hampshire. Wood knew Upton's history well, however, and spent his adult life ministering there. Wood was also the son of a soldier in the War for Independence. He may have been speaking for himself as well as the people of his community when he wrote: “at the expense of much blood and treasure of much and sorrow God gave to our fathers the glory and the happiness of leaving to their children the precious inheritance of liberty and independence.”

Overall, Wood portrayed the war as an event or great significance and part of a legacy of sacrifice. When tasked with reviewing the town’s past, Wood could “find nothing more than of ordinary importance, until I come to the American Revolution. Here are pages of deep interest—pages, written with tears and with blood [.]” When first called to fight, Wood believed that Upton men were reluctant to leave, for they had “an attachment to their rocky soil, to their families, to their firesides, and to their altars [.]” Still, after the alarms rang out from Lexington and other locales miles away, these men “were ready to march. And they did march. Hand in hand, shoulder to shoulder they went fathers and sons together through the Revolution. They suffered - they fought, they bled, and with others, they conquered.”

For Wood, those born after the Revolution (or in his case, just prior to the start of the war) ought to feel grateful for all who came before them to fight. Though some suffered from great financial losses after the war, this was a small price to pay for the legacy of freedom, for “[w]ho in possession of it does not feel himself rich.” Speaking as a man who ministered to the people of his town, he explained that the Revolution “will forever stand as an important era in the history of nations, it will be handed down from fathers to children, yes down until the trumpet of the archangel shall sound and awake the slumbers of the dead.” Wood interpreted the Revolution as something more than a matter of great local or national significance; it was a fight to be remembered for all time.

Reverend Poor – 1935

The Upton historians of the 1930s also stressed the sacrifice of their predecessors, but from more of a remove. Despite the promise of freedom that Rev. Wood and others imagined would be handed down generation to generation, many Americans in the 1930s were now battling with their banks and creditors. The promise of a life of liberty was greatly imperiled by the Depression, a stark reality that bleeds through the words of Rev. William George Poor in 1935.

Poor, who was also a town minister, took to writing a longer history of Upton for its 200th year. He wrote in more detail about the soldiers from Upton who went “supperless” to fight in the American Revolution. Poor’s book also provides important documentation about the men who served with Captain Robert Taft in their first march north in 1775. Poor’s essay on the Revolution also paid homage to the men who joined the Continental Army. This task was complicated by the fact that, in Poor’s words, “scanty records thwart our desire to enumerate the honors thus won for our town by their endurance and valor.” What Poor could find in more detail was Upton’s financial investment in its soldiers. For years, Poor explained, “expeditions called our men forth, and town meetings continued to require more and more assessments for carrying on the war [.]” Using town meeting records, Poor documented the cost of the war in stark terms.

Whereas Wood waxed poetically about the outcome of the war, Poor found a period of difficult readjustment. The men who were away, for days, weeks, and months at a time may have been “hand in hand,” but their burdens where their own at war’s end. In Massachusetts, Shays’ Rebellion presented an alarming possibility: that people fighting for independence may not be able to create a peaceable, or functional government. Poor described the “many hard months of bitterness” that came when “soldiers returned home to neglected farms, mortgages, demands by creditors and their lawyers, trying to deal with valueless money, and facing arrest and imprisonment for debt [.]” Although the citizens of Upton seem to have adjusted to peacetime without any significant unrest, they saw “Arrests for treason, and penalties adjudged therefor occurred in neighboring towns [.]” Poor surmised that local people “must have struggled hard to hold their poise and go back to fertile acres rank with weeds.” But they fought through their “backaches” and dug into newly fertilized lands. With George Washington as President, Upton farmers believed even the ground was “more fertile” and each step of hard work was part of a “long stride of progress on our hillsides as well as over the farm-lands.” For Poor, the lack of social discontent in the face of great hardship was to be applauded. If he took a lesson from this period, it was that fighting in a Revolution was noble, but resisting through a Rebellion such as Shays’ was not.

Her Full Share

In the end, both Rev. Poor and Rev. Wood agreed that the “people of Upton had paid their full share…during the long struggle for ‘liberty.’” The instability wrought by the war was not forgotten by later residents, but it would be overshadowed by later developments. Between Wood’s address and Poor’s history, Upton residents got to work covering Americans head to toe, with carefully crafted hats and shoes. The brogan industry blossomed in Upton, with craftspeople making 87,000 pairs of cheap brogans annually by 1832. These cheap shoes were marketed to Southern plantation owners and worn by enslaved people. Others in Upton entered into the straw braiding business, making a living out of covering the heads of ladies with beautiful hats. Their industries outfitted those who were enslaved as well as those who were free. This arrangement seemed to suit local residents, but nationally, a country so divided could no longer be held together. In 1861, some residents from this community were sent off to fight for the future of the Union.

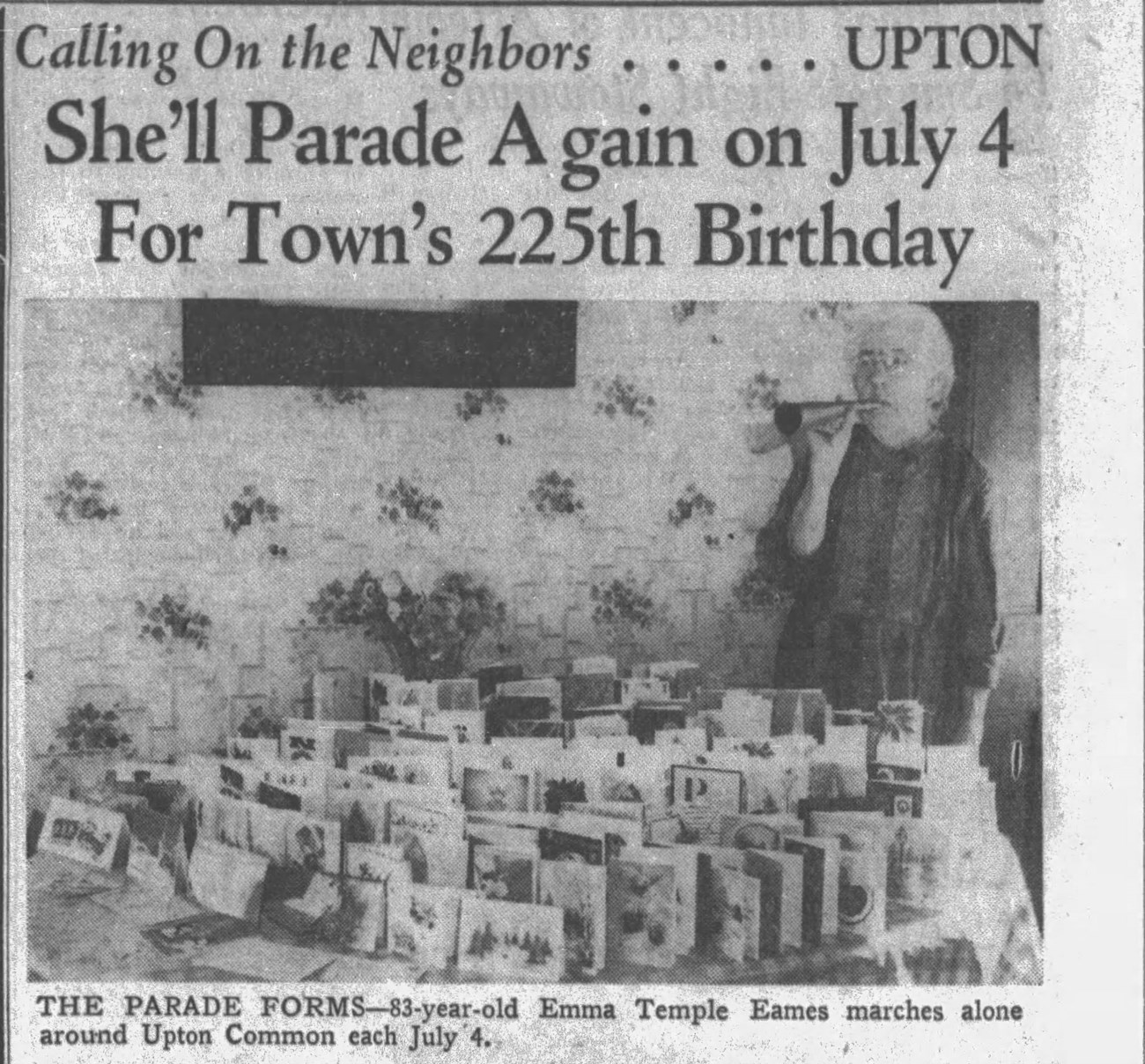

By the time of the country’s centennial in 1876, Upton residents had made considerable contributions to industry. In March that year, a woman named Emma Jane was born to the Temples in Upton, mere months before her country’s birthday. Later in life, Emma Eames would make headlines in 1959 for being a patriotic widow in town and hosting a “1-Woman Parade” on the Fourth of July. Her hometown had stopped hosting a Fourth of July celebration because (one man reported) “the young fellows don’t like to march” and there was a general “lack of interest.” Eames was keen to “toot a tin horn” to rally others, and even championed a large party for the town’s 225th in 1960. Eames knew that a 3-day commemoration “might be too much. People don’t have extra money nowadays.” In this case, Eames was proved wrong. Perhaps inspired by her example, more than 5,000 people turned up to a town parade on July 4, 1960, showing that once again, people were moved to march shoulder to shoulder. Even, or perhaps especially during times of difficulty, some were willing to weigh the cost of inheriting the American Revolution.