Last updated: March 14, 2025

Article

The Westmoreland Slave Plot of 1687

Encyclopedia Virginia

On June 8, 1680, the Virginia General Assembly passed a law entitled, “An act for preventing Negroes Insurrections.” The law began by noting “the frequent meeting of considerable numbers of negroe slaves under pretence of feasts and burials,” thinking that these meetings were “of dangerous consequence.” It also worried about slaves who “lye hid and lurking in obscure places,” and prohibited any slave from arming themselves “with any club, staffe, gunn, sword or any other weapon of defense or offence.” Slaves were also prohibited from leaving his master’s property without a pass and could not “presume to lift up his hand in opposition against any Christian.”

As planters remained concerned even after the law was passed, in November 1682, the General Assembly created an amendment that prohibited enslaved persons from gathering at plantations not owned by their masters for fours at a time. Due to their isolation far from the more densely populated areas of coastal Virginia, Westmoreland County had long worried about their vulnerability to slave uprisings. Even though the county did possess a small militia force, with Lawrence Washington, George Washington’s grandfather, as one of its captains, it did not use them to for anything except defense of the county. It also did not use patrols to mitigate the planters’ risk of an enslaved person escaping from their plantations. Scores of enslaved men and women successfully escaped, and the authorities were concerned that others might be planning revolt. The county’s population of enslaved persons had risen in the years since Bacon’s Rebellion, with most of the enslaved being brought directly from Africa. It is estimated that by the time of the 1687 plot, that the counties comprising the Northern Neck had equal numbers of white farmers and planters and black, almost entirely enslaved, inhabitants.

The plot began in late 1687 when Nicholas Spencer, a member of the Governor’s Council, Secretary of State and a resident of Westmoreland County informed Virginia’s governor Francis Howard, baron Howard of Effingham of a suspected slave conspiracy in his home county. The Council’s writings of the meeting stated that Spencer had “provided Intelligence of the Discovery of a Negro Plott, formed in the Northern Neck for the Distroying and killing his Majesty’s Subjects the Inhabitants thereof, with a designe of Carrying it through the whole Colony of Virginia…” The Council also reported that Spencer “by his Care Secured some of the Prinicipall Actors & Contrivers,” and that only “by God’s Providence” were they captured “before any part of the designes were put in Execution.”On the same day that word was received, Governor Effingham created a special commission to try the suspected conspirators. The commission, including Spencer, Colonel Richard Lee II, and Colonel Isaac Allerton, participated in what was possibly the first oyer and terminer court inpaneled in British North America. These courts, used in times of extraordinary events, would become the main judicial method to try and sentence suspected slave rebels in Virginia for the next 150 years.

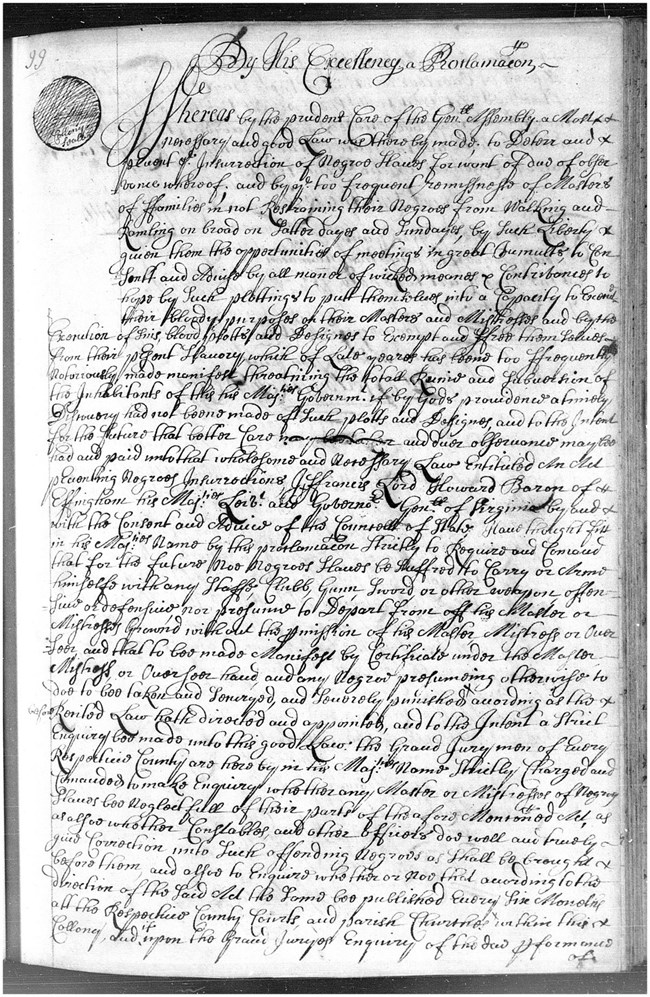

The trial would be known mostly for its brevity. Governor Effingham wanted a speedy trial for the “present Safety” of Westmoreland County and the Virginia colony. With the belief that the court proceedings would more than likely result in the public executions of the suspected rebels, Effingham hoped to “deter other Negroes from plotting or Contriveing” to kill or harm whites. Although the outcome of the trial has been lost to history, it is assumed that the rebels were found guilty and executed. Within days of the verdict, Governor Effingham issued a proclamation that reminded planters of the prohibitions against slaves found in the 1680 act. He chastised them for “not restraining their Negroes from walking and rambling on broad on Satterdayes and Sundayes,” and reminded them that slaves were not to be armed, nor could they leave their masters’ plantations without written permission from a master, a mistress or an overseer. Violators would be met with severe punishment, and owners who were neglectful in their duties could face fines or imprisonment. As a final show of displeasure, the Governor had the 1680 act published every six months at the “respective county courts and parish churches within this colony.”

Although white slaveholders were less apprehensive after the uncovering of the plot, a few other incidents occurred in the following years to keep the tension high in the colony. A slave belonging to a master in Warwick County was briefly arrested on the charge of conspiring with other slaves in Charles City and New Kent counties. In late April of 1688, a slave named Sam, who belonged to a prominent planter in Westmoreland County, was found guilty in a trial held in James City County of having “several times endeavoured to promote a Negro insurreccon in this Colony.” Sam and a handful of followers were severely whipped by the James City sheriff and then were transported back to Westmoreland County, where they were whipped again. As the leader of the group, Sam was forced to wear a heavy iron collar affixed to his neck for the rest of his life, and if he “shall goe off his said master or masters plantacon or get off his collar then [he is] to be hanged.”

The Westmoreland Slave Plot led lawmakers to create a series of restrictions in order to prevent further conspiracies. In April 1691, the General Assembly passed “An act for suppressing outlying slaves,” granting county sheriffs, their deputies, and any other “lawfull authority” the ability to kill any slaves resisting, running away, or refusing to surrender themselves when ordered to do so. If a slave was killed under this act, the slaveowner was entitled to 4,000 pounds of tobacco from the colony government. The act further sought to prevent the “abominable mixture and spurious issue” of mixed-race unions by prohibiting English men or women from marrying any “negroe, mulatto, or Indian man or woman bond or free.”

The Westmoreland plot confirmed long-held fears among the planter class while also provoking new fears. Servitude in Virginia had become largely dictated by race and the 1687 plot was the first conspiracy that did not involve white supporters or participants and would remain that way until John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859. The clear and present danger of slave insurrection remained a constant theme in Virginia society until the Civil War.

(Thanks to Walter Rucker, associate professor of African American studies at Ohio State University for his initial article on this topic)