Part of a series of articles titled The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963.

Article

Chapter 1: And You Wonder Why We Get Called the Weird Watsons

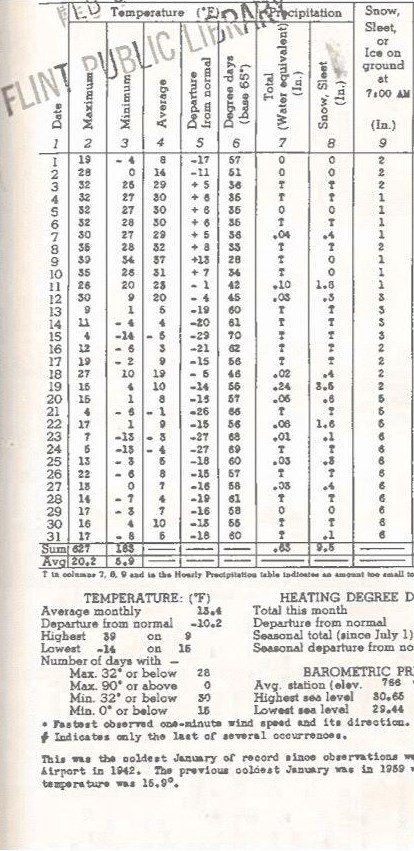

U.S Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau.

It's the winter of 1963, and a terrible cold front has brought frigid temperatures to Flint, Michigan.

Kenny Watson's older brother, Byron, and his kid sister, Joetta (aka Joey), are huddled together with their parents on the couch. It's not just icy cold outside; their heater is broken, so it's freezing inside their house too! The TV newscaster says Flint is in for record-breaking cold temperatures over the next few days, and meanwhile, the weather in Atlanta is in the mid-seventies. Mrs. Watson, who the family calls Momma, hates the cold, and she teases Dad for bringing her to frigid Flint from the warm South. Dad says if Momma had stayed in her hometown of Birmingham, Alabama, she would have married Moses "Hambone" Henderson, and the kids would have had lumpy heads. Dad continues hamming it up, impersonating "Hambone" Henderson by talking in an over-the-top southern accent and foolishly claiming that Nanook of the North (a famous movie about the Arctic) is set in Flint.

The family finally decides that they should stay with Aunt Cydney until their heater is fixed. Kenny and Byron are put in charge of clearing the ice off the family car, a 1948 Plymouth they've nicknamed "The Brown Bomber." Kenny cleans his side but Byron instead gazes at himself in the car mirror and ends up so pleased with what he sees that he goes in for a kiss. His lips freeze to the glass! Dad cracks up when he sees Byron's mouth frozen to the car, but Momma and Joey are worried and fetch hot water. Kenny pours the water on to the glass, but it only makes things worse, and Byron punches Kenny, hard. Eventually, the family detaches Byron from the mirror and Kenny is left clearing the rest of the snow on his own. On the drive to Aunt Cydney's house, Kenny gets payback at Byron, saying he inspired a whole new comic book character: "the Lipless Wonder."

Fact Check: Was Flint especially cold?

Was it especially cold in Flint during the winter of 1963? What was the weather like in Atlanta, Georgia at the same time?

What do we know?

On a typical January day in Flint, the temperature's low point is 16° F, which is below freezing. The January of 1963 was even colder. In fact, 1963 still holds the record for the coldest January 23rd and 24th in Flint's recorded history: temperatures fell to -13° F. Flint wasn't the only place experiencing bitter temperatures that year, however. The cold front stretched across most of the United States, including Atlanta, where it was not 70° F but instead hit lows well below zero.

What is the evidence?

Primary Source:

"Flint had its coldest weather in almost 34 years during the night and early today. The mercury hit 17 degrees below zero downtown and 13 below at Bishop Airport. The 17-below reading shattered Flint records of 11 below for Jan. 23, set in 1926 and tied in 1948, and 7 below for Jan. 24, set in 1961. Journal records, based on downtown readings, go back to 1916."

Secondary Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, "Climatological data for Flint area, MI (ThreadEx) - January 1963," distributed by NOWData.

Secondary Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, "Climatological data for Atlanta area, GA (ThreadEx) - January 1963," distributed by NOWData.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is a government bureau. It provides weather forecasts and data to help communities prepare for weather events. Compare the temperatures between the Flint, MI and Atlanta, GA vicinities in January 1963 using the data below.

| Date | Temperature | HDD | CDD | Precipitation | New Snow | Snow Depth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | Minimum | Average | Departure | ||||||

| 1963-01-01 | 19 | -4 | 7.5 | -17.4 | 57 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 2 |

| 1963-01-02 | 28 | 0 | 14.0 | -10.7 | 51 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 2 |

| 1963-01-03 | 32 | 25 | 28.5 | 4.0 | 36 | 0 | T | T | 2 |

| 1963-01-04 | 32 | 27 | 29.5 | 5.2 | 35 | 0 | T | T | 1 |

| 1963-01-05 | 32 | 27 | 29.5 | 5.3 | 35 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 1 |

| 1963-01-06 | 32 | 28 | 30.0 | 6.0 | 35 | 0 | T | T | 1 |

| 1963-01-07 | 30 | 27 | 28.5 | 4.7 | 36 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 1 |

| 1963-01-08 | 35 | 28 | 31.5 | 7.8 | 33 | 0 | T | T | 2 |

| 1963-01-09 | 39 | 34 | 36.5 | 13.0 | 28 | 0 | T | 0.0 | 1 |

| 1963-01-10 | 35 | 26 | 30.5 | 7.1 | 34 | 0 | T | 0.0 | 1 |

| 1963-01-11 | 26 | 20 | 23.0 | -0.2 | 42 | 0 | 0.10 | 1.8 | 1 |

| 1963-01-12 | 30 | 9 | 19.5 | -3.6 | 45 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 3 |

| 1963-01-13 | 9 | 1 | 5.0 | -18.0 | 60 | 0 | T | T | 3 |

| 1963-01-14 | 11 | -4 | 3.5 | -19.3 | 61 | 0 | T | T | 3 |

| 1963-01-15 | 4 | -14 | -5.0 | -27.7 | 70 | 0 | T | T | 3 |

| 1963-01-16 | 12 | -6 | 3.0 | -19.6 | 62 | 0 | T | T | 2 |

| 1963-01-17 | 19 | -2 | 8.5 | -14.0 | 56 | 0 | T | T | 2 |

| 1963-01-18 | 27 | 10 | 18.5 | -3.9 | 46 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 2 |

| 1963-01-19 | 15 | 4 | 9.5 | -12.8 | 55 | 0 | 0.24 | 3.5 | 2 |

| 1963-01-20 | 15 | 1 | 8.0 | -14.3 | 57 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.6 | 5 |

| 1963-01-21 | 4 | -6 | -1.0 | -23.2 | 66 | 0 | T | T | 5 |

| 1963-01-22 | 17 | 1 | 9.0 | -13.2 | 56 | 0 | 0.08 | 1.6 | 5 |

| 1963-01-23 | 7 | -13 | -3.0 | -25.1 | 68 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 6 |

| 1963-01-24 | 5 | -13 | -4.0 | -26.1 | 69 | 0 | T | T | 6 |

| 1963-01-25 | 13 | -3 | 5.0 | -17.1 | 60 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 6 |

| 1963-01-26 | 22 | -6 | 8.0 | -14.1 | 57 | 0 | T | T | 6 |

| 1963-01-27 | 13 | 0 | 6.5 | -15.6 | 58 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 6 |

| 1963-01-28 | 14 | -7 | 3.5 | -18.6 | 61 | 0 | T | T | 6 |

| 1963-01-29 | 17 | -3 | 7.0 | -15.1 | 58 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 1963-01-30 | 16 | 4 | 10.0 | -12.2 | 55 | 0 | T | T | 6 |

| 1963-01-31 | 17 | -8 | 4.5 | -17.7 | 60 | 0 | T | 0.1 | 6 |

| Sum | 627 | 183 | - | - | 1602 | 0 | 0.63 | 9.5 | - |

| Average | 20.2 | 5.9 | 13.1 | -9.9 | - | - | - | - | 3.4 |

| Normal | 29.9 | 16.0 | 23.0 | - | 1303 | 0 | 1.99 | 15.1 | - |

| Date | Temperature | HDD | CDD | Precipitation | New Snow | Snow Depth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | Minimum | Average | Departure | ||||||

| 1963-01-01 | 47 | 27 | 37.0 | -8.1 | 28 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-02 | 50 | 26 | 38.0 | -7.0 | 27 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-03 | 55 | 30 | 42.5 | -2.4 | 22 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-04 | 54 | 30 | 42.0 | -2.8 | 23 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-05 | 51 | 37 | 44.0 | -0.7 | 21 | 0 | T | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-06 | 49 | 35 | 42.0 | -2.7 | 23 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-07 | 51 | 33 | 42.0 | -2.6 | 23 | 0 | T | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-08 | 43 | 30 | 36.5 | -8.1 | 28 | 0 | T | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-09 | 61 | 28 | 44.5 | 0.0 | 20 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-10 | 62 | 43 | 52.5 | 8.0 | 12 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-11 | 60 | 54 | 57.0 | 12.5 | 8 | 0 | 1.20 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-12 | 66 | 46 | 56.0 | 11.5 | 9 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-13 | 46 | 22 | 34.0 | -10.5 | 31 | 0 | 0.12 | T | 0 |

| 1963-01-14 | 28 | 15 | 21.5 | -23.0 | 43 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-15 | 42 | 20 | 31.0 | -13.5 | 34 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-16 | 48 | 23 | 35.5 | -9.0 | 29 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-17 | 42 | 26 | 34.0 | -10.5 | 31 | 0 | T | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-18 | 47 | 35 | 41.0 | -3.5 | 24 | 0 | 1.64 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-19 | 48 | 44 | 46.0 | 1.4 | 19 | 0 | 0.71 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-20 | 55 | 34 | 44.5 | -0.1 | 20 | 0 | 0.62 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-21 | 34 | 19 | 26.5 | -18.2 | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-22 | 51 | 22 | 36.5 | -8.2 | 28 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-23 | 56 | 8 | 32.0 | -12.8 | 33 | 0 | 0.14 | T | 0 |

| 1963-01-24 | 23 | -3 | 10.0 | -34.9 | 55 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-25 | 41 | 11 | 26.0 | -19.0 | 39 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-26 | 47 | 27 | 37.0 | -8.1 | 28 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-27 | 42 | 17 | 29.5 | -15.7 | 35 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-28 | 36 | 10 | 23.0 | -22.3 | 42 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-29 | 34 | 22 | 28.0 | -17.4 | 37 | 0 | T | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1963-01-30 | 50 | 28 | 39.0 | -6.6 | 26 | 0 | 0.46 | 0.0 | T |

| 1963-01-31 | 52 | 35 | 43.5 | -2.2 | 21 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Sum | 1471 | 834 | - | - | 857 | 0 | 5.10 | T | - |

| Average | 47.5 | 26.9 | 37.2 | -7.6 | - | - | - | - | 0.0 |

| Normal | 54.0 | 35.6 | 44.8 | - | 627 | 1 | 4.59 | 1.0 | - |

Fact Check: Did people name their cars?

Is the fact that the Watsons name their 1948 Plymouth the "Brown Bomber" an example of how they are "weird"?

What do we know?

People often give names to things that are important to them, including cars. And cars were very important to many Americans in the 1960. In fact, the 1960s was the height of "car culture."

The Watsons' car is old, but they chose a name for their vehicle that playfully emphasizes its strength and power: the "Brown Bomber." The name reflects the car’s light brown color—Plymouth called it "Battalion Beige"—but more significantly, the "Brown Bomber" was the nickname journalists gave to the 1937 World Heavyweight Champion boxer Joe Louis. Louis was the second Black boxer to earn that title, and he held it until 1949. He retired from boxing in 1948, the same year the Watsons' Plymouth was manufactured. Joe Louis was a national sports hero but the Watsons might have felt special ties to him since he lived in nearby Detroit.

What is the evidence?

Primary Source: Jan Harold Brunvand, "A note on names for cars," Names 10, no. 4 (1962): 279-84. https://doi.org/10.1179/nam.1962.10.4.279.

University of Idaho professor and folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand compiled a list of more than 180 unique car names he saw while driving in Michigan, Indiana, and other parts of the United States in the early 1960s. Among the names were Bob's Sled, Little Bo Jeep, and Snow Cone.

"Recently the painting of names in English directly on automobiles has become a teen-age fad. Early in 1960 when I became aware of this practice, I began to jot down names as I spotted them. …The names I saw originally were in Indiana and southern Michigan, but through travel and wide correspondence I have found the trend to be national. The duplication of a few names over a broad area suggests that the fad has some commercial circulation now, perhaps as decals, but most names still seem to be hand painted, often in ornate script, on both rear fins of the cars in lettering two to three inches high."

Primary Source:

"Joe Louis will retire as one of the greatest of champions. He wore the heavyweight crown longer than any other man in history—11 years and three days. He defended it often, against all comers. Twenty-five times the Brown Bomber crawled through the ropes in defense of his title. … Joe Louis has been a true champion—in and out of the ring. …Frequently, during the last decade, Joe Louis has been called a 'credit to his race.' That description is not comprehensive enough. He is a credit to the human race. If more of us showed the same idealism, the same rigid adherence to a code of ethics, and an equal amount of modesty and common sense, the world would be a better place to live."

Fact Check: Is Nanook of the North set in Flint?

Is the movie Nanook of the North set in Flint? Are the film's characters Chinese?

What do we know?

Nanook of the North is a 1922 silent film by Robert Flaherty. It is set in the Canadian arctic village of Inukjuak, which is more than 1000 miles north of Flint, Michigan. It features local Inuit people cast in the role of Inuit characters. There are no Chinese characters.

Nanook of the North was a huge commercial success when it was first released and today is recognized as an important contribution to cinematic history: it helped to create the full-length documentary. While the film documented important details about life in the arctic, it also invented scenes that suggested the Inuit of the 1920s were simple, primitive people stuck in the past. The film's perpetuation of stereotypes had a long life: forty-one years after the film’s release, the fictional Mr. Watson—pretending he is Momma's rejected suitor—compared the bitter cold of Flint to that of the Inuit village. It’s a put down that implies that the people of Michigan are not just cold but also simple and primitive.

The racism doesn't stop there. While impersonating Momma's old boyfriend, Mr. Watson calls the people in the movie Chinese. This portrayal highlights the anti-Asian—and more specifically anti-Chinese—prejudice long common in the United States. Just as Inuit were portrayed as "primitive" in Nanook of the North, Asians were often portrayed as "uncivilized" in American popular culture of the time. Lumping Inuit and Chinese people together is a way of 'othering,' or making them seem completely different from other people, especially white people, who were the typical faces of movie and television at the time. Anti-Chinese racism was especially strong in the 1960s because of a popular fear that Chinese Americans were spies for the Communist Party.

What is the evidence?

Primary Source:

Robert Joseph Flaherty and Pathé Frères (U.S.)

Secondary Source: Michelle H. Raheja, "Reading Nanook's smile: visual sovereignty, Indigenous revisions of ethnography, and 'Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner),'" American Quarterly 59, no. 4 (2007): 1159–85, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2007.0083.

"While Nanook is portrayed as heroic and master of his physical environment in other scenes … when he is compared with the world of the [white] trader, he is depicted as awkward and lacking intelligence, an anachronistic [out-of-date] and irrelevant, if quaint, figure in the early twentieth century context of his original audience."

Voices from the Field

"Joe Louis" by Dr. Theresa Runstedtler, a scholar of African American history whose research examines Black popular culture, with a particular focus on the intersection of race, masculinity, labor, and sport.

Runstedtler, Theresa. Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner. University of California Press, 2012.

Writing Prompts

Opinion

State your opinion of the Watson family after reading Chapter 1. Provide reasons for your point of view that are supported by facts and details from the text. Provide a concluding statement related to the opinion presented.

Informative/explanatory

The Watson family lives in Flint, Michigan, and when the novel opens, they are experiencing an extremely cold winter. Locate your current local forecast by consulting a newspaper, app, website, or other technology. (For example, you could use www.noaa.gov, the website of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency, to find your town or city’s current weather forecast. Describe the weather forecast using facts and concrete details. Include charts or formatting that illustrate what you find.

Narrative

Describe a real or imagined experience with extreme heat or cold. Organize your story with an event sequence that unfolds naturally. Use transitional phrases and sensory details to convey the experience precisely. Prove a conclusion that follows from the narrated experience.

Note: Wording in italics is from the Common Core Writing Standards, Grade 5. Sometimes paraphrased.

Last updated: February 4, 2025