Last updated: April 4, 2025

Article

The Untold Story of FDR's Valets

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

When the polio virus attacked FDR’s body at Campobello in August 1921, he lost use of his hands, arms, and legs, as well as control over vital functions. Eleanor, sometimes with the assistance of Louis Howe but often alone, moved him, bathed him, administered catheters and enemas, brushed his teeth, shaved him, and tended to every need day and night. She continued to perform these delicate tasks even after the arrival of Edna Rockey, a trained nurse who arrived from New York City. When FDR’s condition stabilized, he was taken from Campobello to New York Presbyterian Hospital. After nearly six weeks in the hospital, he was released and settled into the family’s very crowded 65th Street house, where Eleanor and the children made room for Miss Rockey and Louis Howe. A month later, he began a strict regimen of daily, often painful, exercise under the direction of physiotherapist Kathleen Lake. Though often cheerful, FDR struggled emotionally too. When he made some of his own suggestions for rehabilitating his muscles, Lake responded tactfully but stern. FDR resented her dismissal of his ideas.1 Secretly, he had Nurse Rockey give unauthorized leg massages every night but was later found out. “He has all sorts of new ideas about developing his muscles,” reported Lake, “& I have to discourage him periodically as tactfully as possible.”2

FDR’s hands and arms were only temporarily impaired. And after three months, he was attempting to walk again. Corrective walking was typically prescribed for polio patients to repair muscular weakness and minimize “habit limps” after the muscles regained strength. In many cases, even though the body was badly weakened, a patient could be taught to walk with leg braces and a crutch.3 The process was difficult, described by historian Geoff Ward: “Once the braces were on . . . it took Mrs. Lake, Miss Rockey, Dr. Draper, and the Roosevelt butler just to get him on his feet.”4 It was soon after that FDR hired Leroy Jones, the first of several valets he would rely on for the remainder of his life. After Jones left FDR’s employment in 1927, a series of valets shared the job—an arrangement FDR humorously referred to as "divided custody."5

A valet, as described in The Servants Practical Guide (published in 1880), is useful to an elderly man, who “renders any services that the state of his master’s health may require; such as sitting up at night, carrying him up and down stairs during the day, when required to do so, or sleeping in his room at night, &c.”6 More typically, the valet was a personal servant responsible for grooming and dressing a man of wealth and high social position. The occupation originated in the Middle Ages, primarily in service at royal households. Over a period of centuries, the valet became a common figure among genteel families of wealth and property. According to The Servants Practical Guide:

Valets are generally kept by single gentlemen and by elderly gentlemen, and seldom by married men, unless by noblemen or persons of considerable wealth. Single men require the services of a valet, unless they keep a butler and footman, when the butler acts as valet. Elderly gentlemen often require the services of a valet in addition to those of the men-servants of their establishments, as constant personal attendance cannot satisfactorily be given by a butler who has other duties to perform.7

In addition to maintaining his employer’s wardrobe, the valet was responsible for performing a range of personal and confidential services. They could be barbers, nurses, waiters, companions, and even public relations agents. For these reasons, valets have long served our presidents, whose demanding schedules and constant travel required such assistance.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

More than a decade before he became President of the United States, Roosevelt hired his first valet in 1922, not because he fit a social profile for men who kept servants, but because his paralysis compelled it. Franklin and Eleanor’s daughter, Anna, recalled, “somebody had to be at his beck and call all the time. It had to be a man. A woman couldn’t lift him or do anything of this sort.”8

There was seldom a time of day that FDR’s valets were free from the pressure of their duties.9 Elizabeth McDuffie, a White House maid and wife of FDR’s valet Irvin McDuffie, recalled how much the president relied on his valet in her unpublished memoir:

He traveled with him to Europe, to South America, to Hawaii. He was with him on campaign trains and vacation yachts. He nursed him through two cases of pneumonia. He cut his hair, helped him dress, rolled his wheel chair, ran his errands, put him to bed, and woke him up in the morning, whether at the White House, Hyde Park, or Albany.10

Photo courtesy of Melinda M. Dart, A Glimpse of Greatness: The Memoir of Irineo Esperancilla.

At all times, the valet had to be available and nearby to assist the president, and especially in case of emergency.11 The need to respond quickly suggests that it was necessary for the valet to sleep under the same roof, as was true for some house servants. But it is not entirely clear if Springwood represented an integrated household. At the White House, the valets—all of whom were of African-American, Puerto Rican, or Filipino descent—lived and worked among a domestic staff that was almost exclusively Black. White House butler Alonzo Fields was surprised by the segregated conditions he encountered at Hyde Park, remembering “whenever the colored help went there to serve the President, they were not permitted to eat in the dining room for the help. They had to eat in the kitchen. Of course at the White House, with Virginia so nearby, the separate dining rooms could be attributed to the influence of that State’s policy, but in New York you did not expect this.”12

Bedroom assignments at Hyde Park are not so clear. We know little about who occupied the ten second-floor bedrooms for the use of household servants. Two rooms on the third floor were for the nurse and governess when the Roosevelt children were young, but in later years, after the children had grown, they provided additional accommodation for a range of household or government employees. In a 1959 interview, Eleanor Roosevelt said that one of these third-floor rooms was used for a time by Irvin and Elizabeth McDuffie and the other by FDR’s security detail.13

NPS Photo.

The work of the valet typically required a dedicated room. Domestic manuals published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries describe the duties of servants and the arrangement of domestic spaces:

Finely planned modern houses have a room devoted to valet’s work. It is finished with conveniences for brushing and pressing clothes, as it is the valet’s business to keep his employer’s raiment above the suspicion of not having just arrived from the tailor. He is an expert at pressing. The fold of his own trousers, as well as that in his master’s, is always clearly defined—one mark of a well-groomed man. A speedy and accomplished packer, he can fold a coat as well as the tailor who made it. An array of boots and shoes of all styles and colors in vogue he must keep in shape over lasts molded after a model. . . . The valet carries away his employer’s laid off clothes at each change. They are not returned until they have been brushed and freshened—equal to the tailor’s latest efforts.14

At the White House, McDuffie had “a bed-room suite, a desk, comfortable rugs and excellent drapery. A telephone is in the room for his use and he has the privilege of living with his wife.”15 The valet’s room at Hyde Park is much more modest, a small workroom too narrow to serve also as a bedroom.16 But it is efficiently located at the door that divides the family rooms from the service wing. The location of the annunciator, directly across the hall from the valet’s room, would have facilitated quick response to FDR’s calls through the night.

FDR’s surviving checkbooks between 1924 and 1933, indicate that Jones and McDuffie earned from $900 to $1,200 per year ($75 to $100 per month). Check payments are inconsistent and irregular, and they were likely more often paid by cash. Checks drafted to McDuffie are difficult to assess because FDR is often paying several months backpay, reimbursing McDuffie for expenses, or adding and deducting salary advances. A valet’s wages were typically equal to that of a butler.17 In 1932, White House Butler Alonzo Fields earned $90 per month (annually $1,080 in 1933) after FDR fulfilled a campaign promise to slash government spending, including reducing salaries of White House staff by 25 percent.18 According to the 1940 U.S. census, a year before he became FDR’s valet, Cesar Carrera’s annual income as houseman was reported to be $1,120. That same year, also according to the census, Roosevelt’s valet, George Fields, earned $1,270 per year, and Lilian Rogers, a White House maid, earned $900 annually. By comparison, Sara Roosevelt’s butler in New York, George Kaln, earned $1,200 per year, and Clifford Smith, Eleanor Roosevelt’s caretaker at Val-Kill, earned $908 per year.

Prior to his terms as President of the United States, FDR paid his valets from his personal accounts. Thereafter, the valets were on the payroll of the United States Navy. Although the Navy adopted the most progressive racial policies of all military branches following World War II, it was not always the case. Black men had served in every war since the American Revolution, but following World War I, they were almost completely absent from the Navy. During the 1920s, Filipino recruits served in the menial roles that were previously held by Blacks, typically assigned to the messman branch and only a few to general service. The Navy only began recruiting African Americans again with the arrival of Philippine Independence. FDR actually played a key role in pressuring the Navy to recruit Blacks.19 But racial policies within persisted, as discrimination and segregation policies characterized the naval experience. When valet George Fields left President Roosevelt to join the Navy, he no doubt experienced the government-sanctioned discrimination described by one recruit, American baseball hall of famer Larry Dobby:

I enlisted and wore a US sailor’s uniform at Great Lakes Naval Training Station. For the first time I was conscious of discrimination and segregation as never before. It was a shock. If you’ve never been exposed to it from the outside and it suddenly hits you, you can’t take it. I didn’t crack up; I just went into my shell. . . . I thought: ‘This is a crying shame when I’m here to protect my country.’ But I couldn’t do anything about it—I was under Navy rules and regulations and had to abide by them or face the consequences.20

Racism was always in the shadows. FDR regularly faced the delicate matter of accommodations while traveling with a Black employee. When planning a three-week sailing excursion from New York to Buzzard’s Bay, FDR’s friend Livy Davis observed “I should think that Roy [Leroy Jones] would present a very difficult problem for he can hardly sleep in the forecastle, and the only place I can think of to stow him is on a mattress on top of a pile of rope in that lazarette.”21 Rental arrangements for an extended trip around the Florida Keys presented the same challenge. FDR asked Manhattan yacht broker J. Fred Tarn if a place could be found for his valet aboard the Weona II. Tarn thought Roy might fit in, if he could take orders from the crew and “had not been impregnated with present so-called ‘rights.’”22 Prejudice and segregation were equally systemic in the North. Arranging a follow-up examination with his doctor in Boston, FDR assured Dr. Lovett’s office “I have a colored boy who helps me get about. I suppose that I can perfectly well . . . have the colored boy come in every morning and get me up and help me about. He would, of course, sleep in a hotel.”23

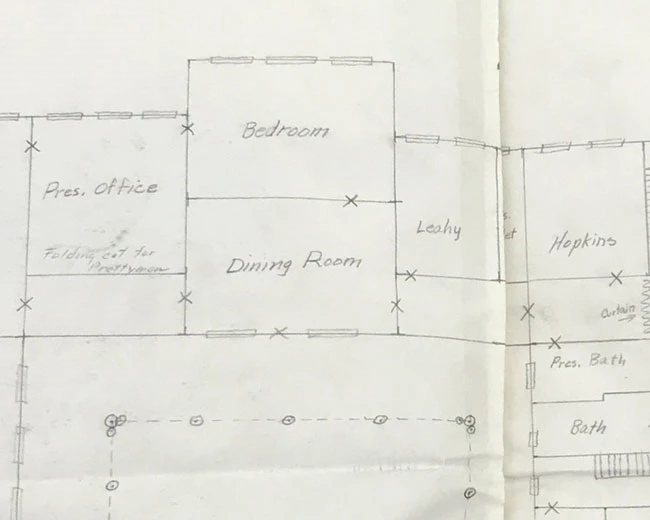

United States Secret Service Records, 6-1, Container 21, Trips of the President, Yalta, 1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

These moments surely provided FDR personal perspective on issues of race in America and how people really lived outside of his world. In rare cases, the valet could help others gain access to the president. Lillian Rogers Parks remembered that “FDR’s valet, McDuffie, and Gus Gennerich, his bodyguard, sneaked people into FDR’s Oval study to talk with him about breadlines and life on poverty row.”24 When Roosevelt’s secretary, Marvin McIntyre, refused NAACP leader Walter White an appointment with the president, “McDuffie, who sometimes leaves notes on the president’s pillow and tactfully gets unofficial callers in through the White House kitchen, was able to arrange a private meeting.”25Many associates closest to FDR have been the subject of their own history, recognizing the importance of these relationships with the president. Some, like Louis Howe, Grace Tully, Harry Hopkins, and Missy LeHand, are the subjects of single biographies. FDR employed at least six valets between 1922 and 1945, all of them men of color, but they have largely been forgotten or overlooked, occasionally warranting only a passing reference. Most of them left little record of their life and career, perhaps in respect to FDR’s privacy so soon after his death, or in deference to the confidential nature of their position as a trusted employee. The valets were essential to FDR’s life and so much a part of who he was. As Irvin McDuffie put it, “Next to his wife, I am around the President more than anyone else.”26 Through the service they rendered and the crucial role they played in FDR’s private and political life, their stories rightly belong at the forefront of history.

Frank Futral, Shelby Landmark, PhD, and Seth Frost

The authors thank historian Geoff Ward who shared information and insight for this article.

1 FDR’s correspondence with other polios, physicians, and therapists illustrates a vast understanding of popular and experimental treatments. As noted by historian Geoff Ward, “Franklin Roosevelt never enjoyed being told what to do by anyone.” See Geoffrey C. Ward, A First-Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt, 1905-1928, Vintage Books, 2014, p. 626. Years later, when FDR was elected governor of New York, his predecessor Al Smith sought to influence Roosevelt. FDR confided to Frances Perkins, “I mustn’t allow myself to be pushed around, because I might get into the habit. It would be easy because I haven’t got my full strength.” See Oral history interview with Frances Perkins, 1955, Columbia Center for Oral History. Copyright by The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York.

2 Quoted in Geoffrey C. Ward, A First-Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt, 1905-1928, Vintage Books, 2014, p. 625.

3 Alice Lou Plasteridge, “Corrective Walking,” The Polio Chronicle (October 1932)

4 Geoffrey C. Ward, A First-Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt, 1905-1928, Vintage Books, 2014, p. 624.

5 Lillian Rogers Parks and Frances Spatz Leighton, The Roosevelts: A Family in Turmoil (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall Inc.), 56.

6 Anon. The Servants Practical Guide: A Handbook of Duties and Rules. London: Frederick Warne and co., 1880, p. 173.

7 The Servants Practical Guide: A Handbook of Duties and Rules, 1880, 172.

8 Reminiscences of Anna Roosevelt Halsted, 1973, Columbia Center for Oral History, p. 7. Copyright by The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York.

9 Parks, 56.

10 McDuffie, Elizabeth S., Manuscript, The Back Door of the White House, circa 1960. Elizabeth and Irvin McDuffie Papers, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

11 Melinda M. Dart, ed. A Glimpse of Greatness: the Memoir of Irineo Esperancilla, 2022, p. 16.

12 Kevin M. Burke, Robert Heinrich, and Steven J. Niven, The Roosevelts and African American Civil Rights Leaders, Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University in association with the National Park Service, p. 74. Alonzo Fields, My 21 Years in the White House, 42.

13 “Transcript of Taped Tour of the Home, Carriage House, Etc. By Eleanor Roosevelt with Mr. Cotter of NPS,” November 21, 1959. “We will go upstairs to the third floor. These two little rooms on the landing were used for two servants from the White House—Lizzie McDuffie and her husband, who for many years was my husband’s valet. And she was one of the maids both in the White House and here. Now after he was Governor and later President, this room was always used for the State Police who had a bodyguard, or the City Police, as might be, and then for the Secret Service. There were two beds, and they used this room, but the rest of the floor was nursery.”

14 Mary Elizabeth Carter, Millionaire Households and their Domestic Economy: With Hints upon Fine Living, New York, D. Appleton & Company, 1903, 234-5.

15 Frederick Weaver, “President Roosevelt’s Valet,” The Enterprise, July 20, 1933.

16 The valet’s room is identified on a set of plans drafted in 1941 by the Historic American Buildings Survey. Eleanor also referred to this room when arranging to supplement the Springwood staff with staff from the White House for the 1939 royal visit: “Jennings will have to allow the maids to user her pressing room entirely alone whenever they wish, and the men will have to use the valeting room whenever they wish entirely alone.” Eleanor Roosevelt to Sara Roosevelt, May 19, 1939. (Letter reprinted in the Warm Springs Newsletter in my files).

17 According to Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), a valet’s wages were typically equal to a butler’s wages.

18 Kevin M. Burke, Robert Heinrich, and Steven J. Niven, The Roosevelts and African American Civil Rights Leaders, Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University in association with the National Park Service, p. 73.

19 The Negro in the Navy: United States Naval Administrative History of World War II #84. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/negro-navy-1947-adminhist84.html

20 Quoted in Jerry Malloy, “Black Bluejackets,” The National Pastime, Winter 1985, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 72-77.

21 Quoted in Ward, A First Class Temperament, p. 671.

22 Ward, A First Class Temperament, p. 660.

23 Ward, A First Class Temperament, pp. 664-5.

24 Lillian Rogers Parks and Frances Spatz Leighton, The Roosevelts: A Family in Turmoil (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall Inc.), 56.

25 The McDowell Times. April 01, 1938, Page 4.

26 Frederick Weaver, “The President’s Valet,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 15, 1933.