Last updated: January 21, 2022

Article

The Unique Management Challenges of the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River

Content submitted by: Steve Lantz, Big Bend National Park and Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River

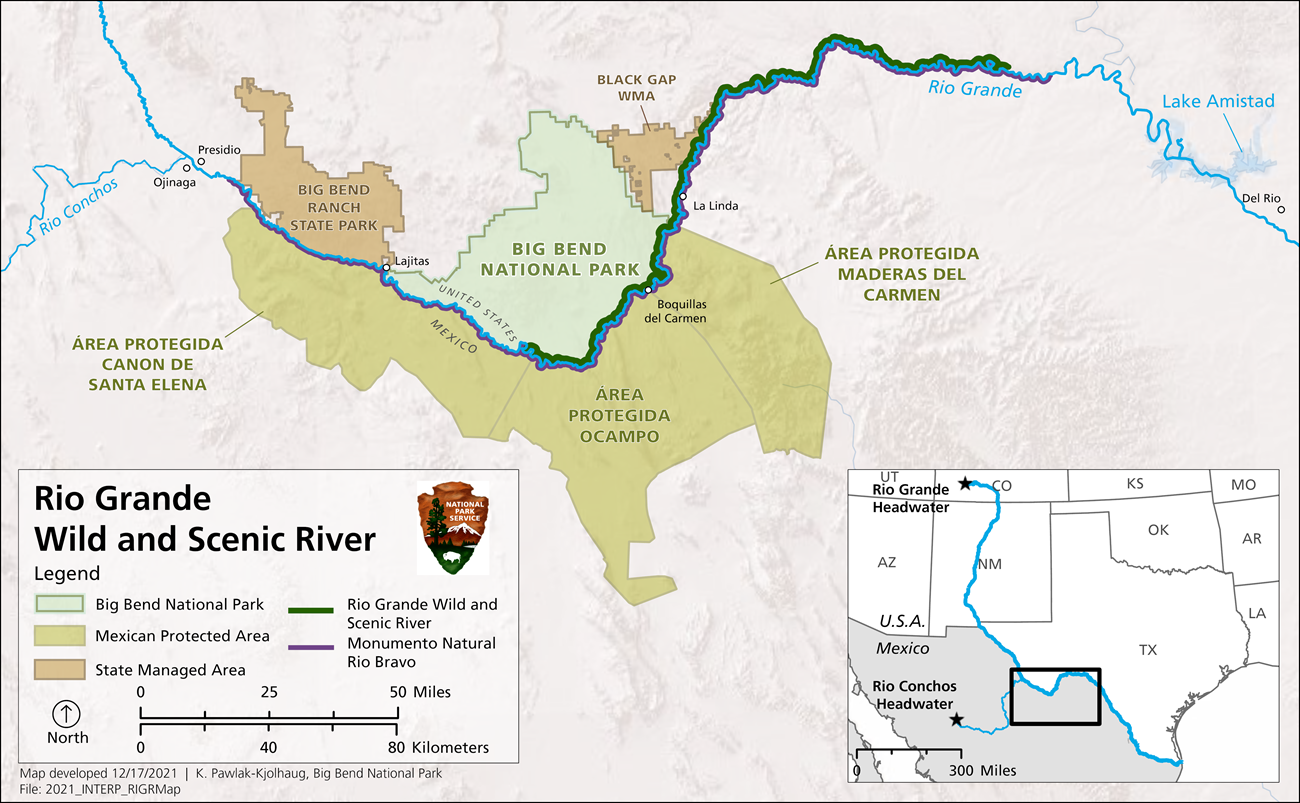

On most maps, the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River simply defines a length of the geopolitical boundary between the United States and Mexico. On the ground, the 199.2 mile Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River lies within a stunning binational Chihuahuan desert ecosystem accompanied by rich history and abundant natural and cultural resources. Most maps also show the Rio Grande flowing from the basin headwaters in Colorado through New Mexico, into Texas, and along the United States/Mexico border to the Gulf of Mexico. However, most surface water that flows into the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River no longer originates from upstream in the Rio Grande, but from the Luis Leon Reservoir in Mexico via the Rio Conchos River with sporadic and often high intensity supplemental water provided from local rainfall events. This source water alteration has reshaped the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River corridor.

The Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River alternates between wide floodplains and narrow towering limestone canyons. Numerous wildlife, botanical, geological, paleontological, and archaeological resources are nestled in the banks. Rural communities rely on the river and the springs that flow from the limestone cliffs as a water source. Historically, the river meandered through the wide floodplains. The main channel was periodically repositioned by flood pulses in a laterally unstable riverbed. The magnitude of river flow is now substantially reduced from historic levels by a series of upstream dams prescribed by a binational treaty to support municipal and agricultural water needs of the United States and Mexico. The flood pulses that would maintain the channel or the larger flood events that would clear the channel of sediment and debris are now fewer and reduced in magnitude. The lower reaches of the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River benefit from groundwater influx via springs and seeps and the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River in the river corridor downstream of the Big Bend National Park boundary has become a largely groundwater dependent ecosystem. The region still experiences regular high intensity rain events that transport sediment out of ephemeral streams and arroyos into the Rio Grande channel. The combination of sediment load and lack of channel maintaining and clearing floods has created habitat where invasive riparian vegetation has taken hold. The cumulative result is a channelized riverbed resistant to natural geomorphologic changes under today’s flow conditions.

The future of the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River depends on binational partnership. The binational importance of the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River resource is reinforced by the presence of Big Bend National Park (36 percent land ownership) and State of Texas Black Gap Wildlife Management Area (13 percent land ownership) along the United States riverbank (remaining downstream United States land is privately owned) and the Santa Elena, Ocampo, and Maderas Del Carmen Protected Areas along the Mexico riverbank. The current condition of the river was influenced largely by a binational effort to protect municipal and agricultural water resources. A similar collaboration focused on environmental flows – with full consideration of environmental impact, flood conveyance, municipal and agricultural water needs – might do the same for the ecosystem and rural communities supported by the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River.

Scott Taylor, NPS BIBE Pilot