Last updated: October 28, 2020

Article

The Tragedy…and Triumph of President James A. Garfield and Alexander Graham Bell

Library of Congress

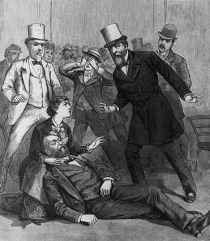

“I am a dead man…” said President James A. Garfield as he lay in a pool of blood on the floor of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station July 2, 1881. As onlookers stared in awe and wept, several men accompanying the President apprehended the shooter, Charles Guiteau, and the others quickly swept up the President and transported him to the White House.

The question of the bullet was a curious one. Exploratory surgery was not done in the 19th century and X-rays were not yet invented, so the doctors attending James Garfield used the most primitive instruments – their fingers – to probe the entry wound in his back and try to manually locate the bullet. Bedridden, stoic, and even conversational, Garfield endured this crude method of examination for three weeks with no firm conclusion. Then a glimmer of hope came from an unlikely source – the inventor of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell.

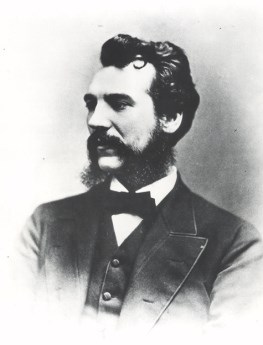

IEEE History Center

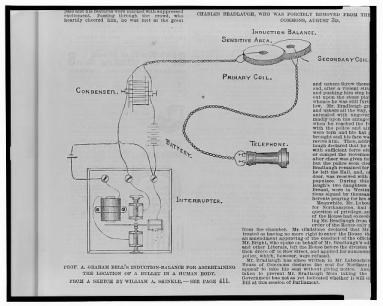

By 1881, Mr. Bell was at the height of his career. The telephone, patented in 1876, earned the Bell Telephone Company its first million, the first corporation to achieve that benchmark inside of one year. Bell constantly invented and improved his creations, and a week after the shooting Bell felt he could help the President’s case by applying his telephone technology to a machine developed by Simon Newcomb, called the induction balance machine. The idea was that the machine could create an electric current and by passing coils over a mass, in this case a human body, any trace of metal would be detected and create a sound by interrupting the current. The amplification device which allowed telephone users to hear a voice from the other end of a phone line would be used to magnify the sound of the interruption on the induction balance machine, thus allowing Bell to pinpoint the location of the bullet.

From the time he arrived in Washington on July 26, 1881 Bell worked tirelessly with his assistant, William Taintor. The pair scrounged for parts to connect the amplifier to Newcomb’s apparatus, and experimented with lengths and locations of the coils which would be used to scan the President’s body. When the machine was in working order, they conducted several trial runs to test the ability of the coils to pick up the presence of lead. Both men hid bullets in their cheeks, in sacks of cotton, in corpses the approximate size of the President, and finally inside of raw beef. Met with success every time, the professors brought the contraption to the Army War Hospital and used it on Civil War veterans with spent bullets in their bodies. All trials were successful, and with some minor tweaking an anxious Bell was ready to try it on his most famous patient: the President of the United States.

Library of Congress

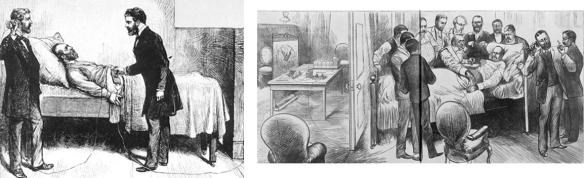

A confident Bell and Taintor arrived at the White House with high hopes the morning of July 26. Those hopes were replaced by shock as Bell caught his first glimpse of the sleeping President. “His face is very pale – or rather it is of an ashen grey colour which makes one feel for a moment that you are not looking upon a living man,” Bell observed. Feeling the sense of urgency, the anxious orchestrator immediately began setting up the equipment.

When Garfield awoke, his attending physicians prepared him for the experiment. His dressing gown was pulled to one side, and with support from an attendant, Garfield slowly rotated his body to expose the wound and surrounding areas. “A calm peaceful expression” came across Garfield’s face, and he closed his eyes as the testing began. Dr. Willard Bliss, the doctor in charge of Garfield’s case, took the coils from the induction balance machine and scanned the President’s body near the bullet hole in his back. This puzzled Bell, since Bliss predicted the bullet was near Garfield’s abdomen in the front of his body. Nonetheless, Bell took his place behind the President, listening in anticipation of that magic sound coming through the telephone earpiece.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 20, 1881. Library of Congress.

“THE PATIENT STILL MAKING GOOD PROGRESS – SUCCESSFUL EXPERIMENTS WITH THE INDUCTION BALANCE—THE BULLET IN THE PLACE FIRST DECIDED UPON BY THE SURGEONS” was the morning headline on August 1, 1881. The New York Times printed a report given by Alexander Graham Bell on his attempt to locate the bullet: “…on July 26, a feeble tone was perceived…but too feeble to be entirely satisfactory.” Based on Bell’s earlier attempts at concealing bullets in meat, corpses, etc, he expected a louder sound when the coils were placed near the bullet in Garfield’s body. Bell took the machine back to his lab, made some further modifications, conducted some more bullet-in-flesh experiments, and returned confidently to the White House on August 1 for a second try. The Times reported after this attempt that “it is now unanimously agreed that the location of the ball has been ascertained with reasonable certainty…” in Garfield’s abdominal wall toward the front of his body below and to the right of his belly button.

Bell was guardedly pleased at the positive response from the doctors, although he himself knew the truth. The induction balance machine did not record a significant difference in sound when waved over different parts of Garfield’s body on August 1. Bell was not satisfied, but the medical professionals had closure and the matter was laid to rest.

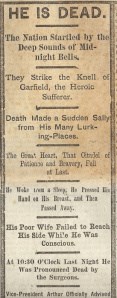

On the morning of September 20, 1881 the newspapers, which for 80 days had religiously detailed the President’s medical condition, had a new headline: “He is Dead.” Upon autopsy of the President’s body, the bullet was found to the right of Garfield’s spinal cord, rendered harmless by a layer of scar tissue that formed around it. Bell was understandably upset by these results, which showed the bullet was nowhere near where the doctors thought it was. Had he been permitted to scan Garfield’s body thoroughly during his examination, Bell quite possibly could have located the bullet. Despite the successes of his earlier experiments, Bell returned home a defeated man, fearing his reputation was soiled and the lifesaving potential of his machine’s lost on this bad news.

After mentally healing from the death of President Garfield, Alexander Graham Bell rose above tragedy to triumph. He mended whatever reputation he believed damaged from his failure to save the President and went on to perfect the induction balance machine, known today simply as a metal detector. These machines are commonly available and affordable. People use them as a form of recreation to find coins, old nails, and perhaps treasure, but very few hobbyists realize the contraption they are holding was first conceived to save a wounded and dying President.

Written by Allison Powell, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, August 2012 for the Garfield Observer.