Last updated: October 25, 2020

Article

The Story of “Uncle Joe” Rudolph

Hiram College Archives

The small single engine plane flew low over Mentor, Ohio, allowing the 90-year-old passenger a good view of the scenery below. Uncle Joe waved to the children on the ground, thoroughly enjoying his first trip on an airplane. After landing he told his nephew, James R. Garfield, that he could now leave this world and meet up with his late wife and sister without embarrassment. Uncle Joe had been angry with himself for avoiding any trips on the newfangled machine.

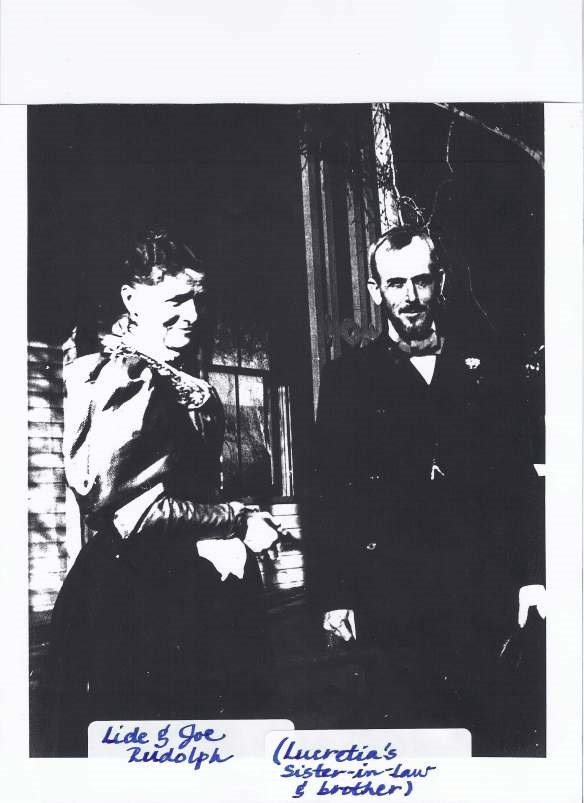

Joseph Rudolph was born September 13, 1841 in Garrretsville, Ohio, the third child of Zeb and Arabella. He had an older sister, Lucretia, who would marry future President James A. Garfield. Joe was raised on a farm, an ideal place for a young boy to get into trouble. One summer day the younger Rudolph and a friend came upon a mud hole with a collection of hogs wallowing in it. The boys decided to chase away the animals and dive into the mud hole. It was great fun until Joe walked home to the farmhouse, where his mother somehow did not approve of the mud hole playground.

Several years later the Rudolphs moved a short distance to Hiram, Ohio so Joe’s older brother John and Lucretia could attend a more modern school. Later Zeb would build a home in the center of town where the Rudolph family lived for nearly 30 years. Joe spent his formative years here, eventually attending the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (today’s Hiram College).

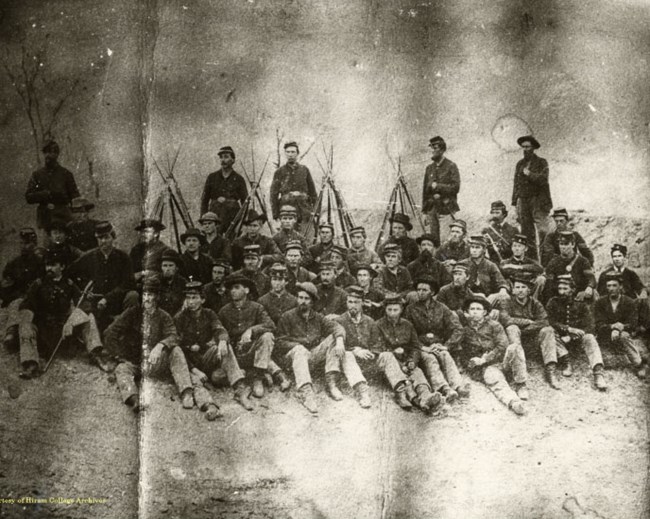

Though not a great scholar, Joe managed to handle the classwork at the Eclectic until April 1861 when the Civil War began. He and several other friends began sleeping on the floor and taking long walks before breakfast. This was done to prepare for enlistment in the Union Army. When the call for volunteers came, Joe, still shy of is twentieth birthday, joined the 19th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, a three-month enlistment. The regiment trained in Painesville where the town hotel served them meals and the Seminary girls showed them every kindness. When the 19th was transferred to Cleveland, Joe recalled the spirited farewell. He remarked, “At the station we had about the liveliest skirmish of our whole term of service. Each one of the hundred boys kissing two hundred Seminary girls goodbye, with the town girls thrown in, was a somewhat lengthy, but not tedious ceremony.”

Upon arrival in Cleveland Joe promptly deserted the 19th OVI and joined his friends in the 23rd regiment. They did their training at Camp Taylor until late June 1861, when the 23rd was ordered to Camp Chase in Columbus. A month later they left for Virginia, where the regiment saw little action until winter brought an end to the campaign. Joe camped with his friends from Hiram and survived a wave of camp fever that took the lives of a number of soldiers from the regiment.

Garfield family photo

In late February 1862 Joe applied for another transfer, this time to the 42nd OVI, commanded by his brother in law, James A. Garfield. Joe managed to get two weeks leave in the process, allowing him to take a leisurely trip home to Hiram. After some welcomed home cooking he left for Kentucky to join Company A of the 42nd, which was made up of Joe’s classmates from the Eclectic Institute. He took part in the end of the Sandy Valley Campaign, where several regiments of Confederates were chased all the way back to Virginia.

While on duty months later in Tennessee, Joe received his first and only wound of the war. The 42nd was on a raid of the town of Tazewell, where Company A stopped a local citizen and stole his saddlebags. Among the contents was a quart bottle of whiskey. On the march back to camp Joe and the boys took several side trips to the bushes and drained the bottle. A short distance later the wobbly soldier lost his balance and fell off the trail into a pile of stones. Joe‘s forefinger got wedged under his musket, causing a severe wound. After the war he would tell a fancy tale of the incident. Joe would say, “I noticed no damage until we were in camp, where I found that the finger joint was smashed. But I am not sorry, as I have ever since been able to show that I suffered for my country.” Days later on a similar raid, Joe would see hundreds of Confederate soldiers just yards in front of him cut to pieces by Union artillery.

There were more incidents in the area near Tazewell. Rumors spread that Confederates were gathering on top of a nearby ridge. The 42nd was ordered to charge the ridge and remove the enemy troops. Halfway up the hill the boys came upon a huge berry patch. They had not eaten since the previous day. The entire regiment came to a halt, including the officers, which lead to an all-out assault of the patch. Joe would later describe the carnage. He stated, “The officers’ mouths so full of berries that they could give no orders, leastwise none that we could or cared to understand. Having filled our stomachs, we proceeded to the top. Not a Johnnie in sight.”

Of course it was not all fun and games for Joe. The 42nd took part in the Vicksburg campaign and saw serious action at Chickasaw Bluffs, Thompson’s Hill, and the Black River Bridge. They attempted a frontal assault on the city of Vicksburg, which became a futile effort to dislodge the Confederates. Joe recalled making a charge and seeing an enemy artillery shell heading right for him. He froze while the shell exploded about 40 feet from where he was standing. Fragments flew by on either side but failed to touch him.

There were many casualties at Vicksburg, the Hiram boys included. Some of the soldiers were killed by friendly fire, when clouds of smoke obscured the difference between blue and gray. On July 4, 1863 the Confederate army surrendered to General Grant. The Vicksburg campaign came to an end. Joe had “seen the elephant” after two years of hard fighting. He received a promotion to sergeant of Company “A” for his conduct as a soldier on the field.

Despite the intense fighting at Vicksburg, Joe and the boys still found time for more mischief. The 42nd was being transported on a steamer when Company “A” noticed a large barrel of fresh apples being loaded on board. They found a long pole, tied a bayonet to the end and quietly speared all the apples they could eat. The next morning they stole the captain’s breakfast by maneuvering the pole through a stovepipe opening above his table. Though the 42nd were now seasoned combat veterans and had seen the horrors of war, they still were boys at heart.

Garfield family photo

After the Vicksburg campaign, Joe was sent to New Orleans along with the 42nd. There was little to do there except court the local ladies who grew fond of the boys in blue. There would be marches and counter marches, but very little action over the next year. Joe received another promotion to Captain and Assistant Quartermaster, which meant he would stay in the army after his enlistment expired in the fall of 1864. Joe saw duty in Louisiana and Texas, where he set up warehouses and supply depots for Union brigades. He returned to civilian life in December of 1865.

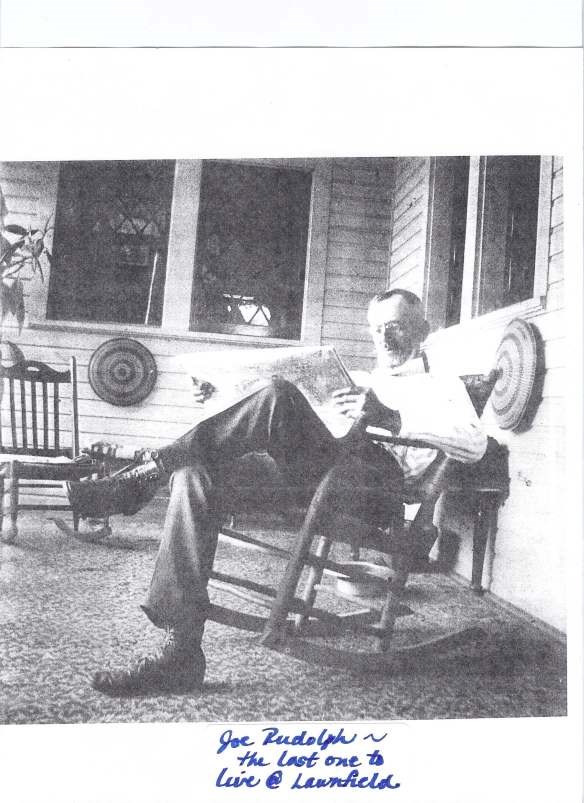

In the 1880’s Joe would move to Mentor to live with his older sister, Lucretia, and his niece and nephews. He settled in the third floor apartment with his wife and his two sons. Joe became the gentleman farmer, overseeing the workers at the Garfield farm. When the United States declared war with Spain in 1898, the fifty-seven-year-old Joe attempted to enlist. Years later he was on vacation in England where he met some English soldiers on their way to action in World War I. Joe called out to the boys, saying, “I know what you are experiencing and I wish I were able to go with you!” One has to think if the soldiers had an extra rifle a certain Civil War veteran would have been seen charging out of the trenches in the French countryside.

The rest of Joe’s ninety-three years were lived in quiet comfort at his sister’s home, where he was the last Garfield family member to live in the home that is now the main attraction at James A. Garfield National Historic Site. Quiet and comfort…except for the day when a young female pilot knocked on the Garfield front door. There was still one more great adventure for Uncle Joe.

All quotes attributed to Joseph Rudolph, Pickups from the American Way, Hiram Historical Society, 1941.

Written by Scott Longert,Retired Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, September 2012 for the Garfield Observer.