Last updated: January 24, 2025

Article

The Saylesville Massacre and American Tradition

Introduction:

"The Inhabitants are greatly enraged and not without Reason...Most all the Town [was] in Uproar & Confusion."

- Entry from the diary of John Rowe, March 5, 1770 about the Boston Massacre

“And it was just like a war, it was at Saylesville… You couldn’t even breathe, they had bombs…tear bombs and you couldn’t breathe…it looke just like a war.”

- Kathryn McGovern, Central Falls, in interview about 1934 Strike at Saylesville.

“They’ve been killing us forever – hundreds of years. They wanted a war, they got one.”

- Statement recorded in a TV interview, June, 2020 during a Black Lives Matter protest in Washington D.C.

“We are representing 74 million people who got disenfranchised… We are a force to be reckoned with.”

- Statement of a participant in the January, 2021 storming of the U.S. Capital in protest of the 2020 Presidential Election

Right: Headstone in Moshassuck Cemetery with two bullet holes

Left: Boston National Historical Park

Right: J. Hendrickson

Protest is, perhaps, fundamentally American. People have expressed dissent through protests from the early years of the American Revolution. A legacy of American protest is still alive and well today. But how do we reckon with a protest that ends in violence?

At Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park, rangers have worked with community members to explore the complex legacies of violence that haunt local landscapes. This essay by Ranger Mark Mello takes a closer look at a 1934 massacre in the Blackstone Valley. It asks us to consider how the event aligns with other moments of violence, starting with the American Revolution and coming closer to the present with more recent episodes of national unrest.

The Walk

On a pleasant mid-June evening in 2022, a group of around 50 people congregated in the Moshassuck Cemetery in Saylesville, Rhode Island. In this peaceful final resting place for hundreds of souls, our intrepid group of Walkabouters (my unofficial name for folks who join us for our summer Ranger Walkabout series) gathered to discuss a traumatic moment in labor history. Over several days in September 1934, this serene resting place for the dead became a turbulent battleground for the living. When the smoke cleared from the violence and chaos, two people were dead. This event would later be dubbed the Saylesville Massacre.

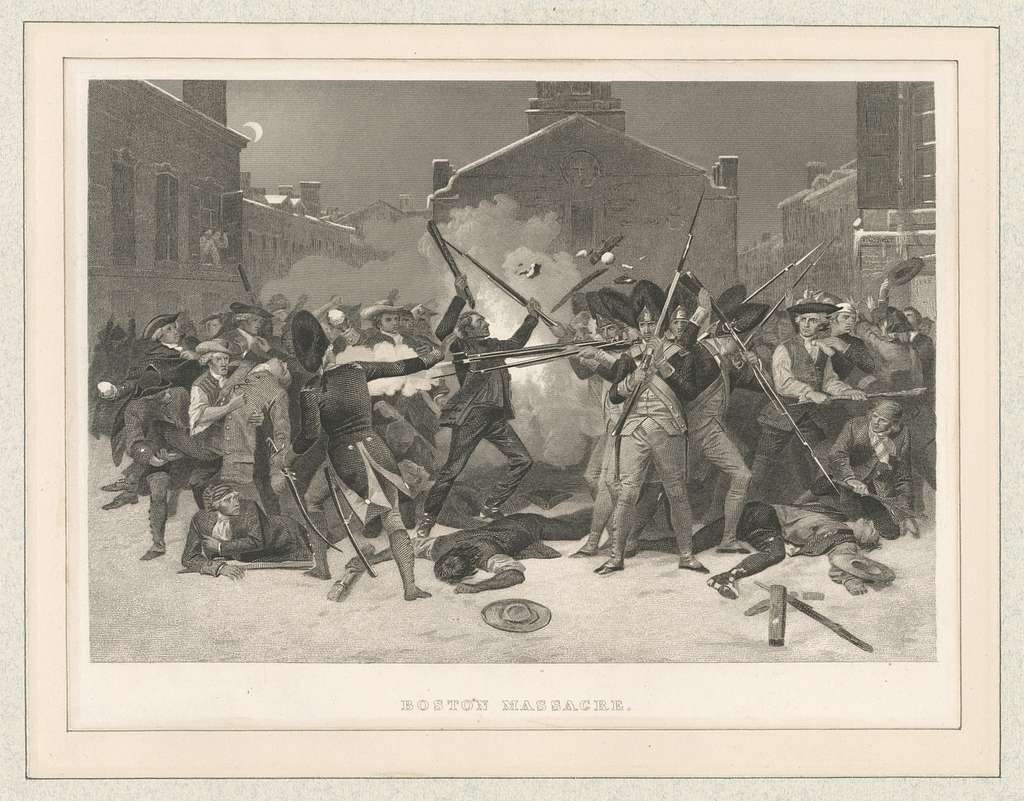

Massacre. This word has often been used across United States history. Perhaps one of the most well-known is the Boston Massacre. On a cold evening in March 1770, a group of colonial protestors assaulted a group of British Regulars in the shadow of the Old State House. The troops stood their ground amid the hail of snowballs, rocks, and insults. Panic ensued with the soldiers indiscriminately firing into the crowd. When the smoke cleared, five individuals lay dead and numerous wounded. This event, labeled a “Bloody Massacre” by Paul Revere and other members of the Sons of Liberty, became a rallying cry against English rule in the colonies. It was a turning point on the long road to independence.

But this is an article about the Saylesville Massacre. Why invoke an event that happened 164 years before? There are many parallels between these two events, but perhaps the most pertinent of these, is a tradition as old as the country itself: Protest. Protesting injustice might be as American as baseball or apple pie. Whether protesting colonial rule, racial injustice, or labor inequities, the annals of U.S. history are filled with stories of civil and sometimes uncivil disobedience. As we commemorate America250, it is necessary to understand these circumstances and what sometimes drives Americans to start throwing stones.

The Place

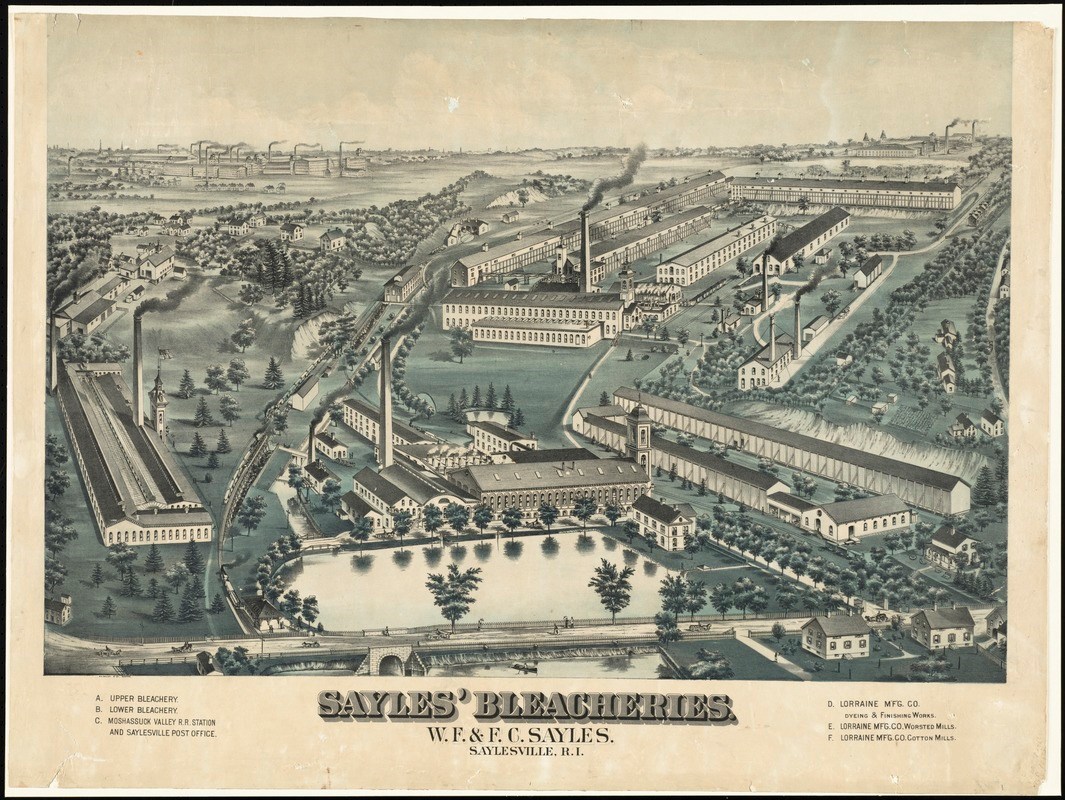

Hanging directly over my desk, within a large and faded bronze-colored frame is an aerial view of the Sayles’ Bleacheries as it would have appeared in the late nineteenth century. Established as the Sayles Finishing Plant in 1847, the company reflected a meticulous and well-organized administrative and management structure over a century of operation. Proponents of Scientific Management, or Taylorism, Sayles’ Bleacheries were noted for their efficiency. This strict management led to labor unrest in 1905 and 1922. The bucolic scene hanging over my desk makes no allusion to this. Well-trimmed buildings with American flags flapping in the breeze sit within what appears to be a rural setting. Although massive industrial complexes loom in the distance, the Bleachery’s buildings stand amongst shrubs and trees. The quaint mill pond and Moshassuck River, with well-dressed locals walking along its banks or riding in their horse-drawn carriages, paint a blissful scene. An adventurous individual is even riding a bicycle. Besides the smokestacks billowing a black cloud, Saylesville looks like a place one would want to take their family for picnic.

As I stare at this image and admire its details and intricacies, I am struck by what is not depicted. The mill houses, the places of rest for the many employees of the Bleachery, are largely missing, replaced by trees and green space. These compact mill houses were the home of the numerous families all in some way connected to the mill or one of its surrounding counterparts. There is something else this illustration cannot capture. No reference is made to the pungent smell emanating from the complex. Bleaching throughout human history has been a heavily chemical process. A key step in bleaching cotton to make it that vibrant white color most would associate with cotton is called “souring.” The process entailed treating boiled cotton in chemic (a chlorin-based mixture). The resulting smell was like burnt vegetables mixed with sugar and chlorine. The noxious smell seared the nostrils of all who walked by. Also missing is any indication of industrial waste disposal. The idyllic mill pond and river would have been filled with literal trash and runoff associated with the bleachery’s operations.

These factors, when combined, created a very different reality than what is depicted. Finally, and perhaps most notable for our story, on a knoll just to the left of the main bleachery buildings, trees replace headstones. Missing entirely from the painting is the Moshassuck Cemetery.

The Moment in Time

The year 1934 was a time of labor unrest. There were over 1,800 strikes involving more than 1.5 million workers in the United States. During the Great Depression, the textile industry was particularly hard hit. Layoffs led to “stretch outs,” or fewer workers being expected to do more work for no additional pay. The United Textile Workers (UTW), an upstart union, saw a surge in membership from 15,000 in 1933 to nearly 250,000 members the next year. The National Industrial Recovery Act or NIRA, legislated in 1933, legalized union organizations for the first time in U.S. history. NIRA and the Great Depression served as catalysts for the meteoric rise in membership experienced by the UTW in 1934. At their annual convention that August, the membership’s rhetoric became increasingly vitriolic. Layoffs, “stretch outs,” and the general decline of working conditions during the Great Depression were taking their toll. The convention voted 561 to 10 in favor of a national strike.

The reverberations of this decision were felt across the nation. Massive walkouts and strikes occurred in textile operations across the country. It was acutely felt here in Rhode Island. On the day after Labor Day, Tuesday, September 4, 1934, picketing began across the state. At first, the strike was remarkably peaceful. Many textile mills ceased operations because of the strike with only a few remaining open. The Sayles’ Bleacheries remained in operation, and although very few working at the bleacheries were members of the UTW, it began to attract a lot of attention. As Governor Theodore Francis Green noted, “At such a time it is easy for passions to be aroused and when passions are aroused acts of violence are apt to occur.” Occur it would.

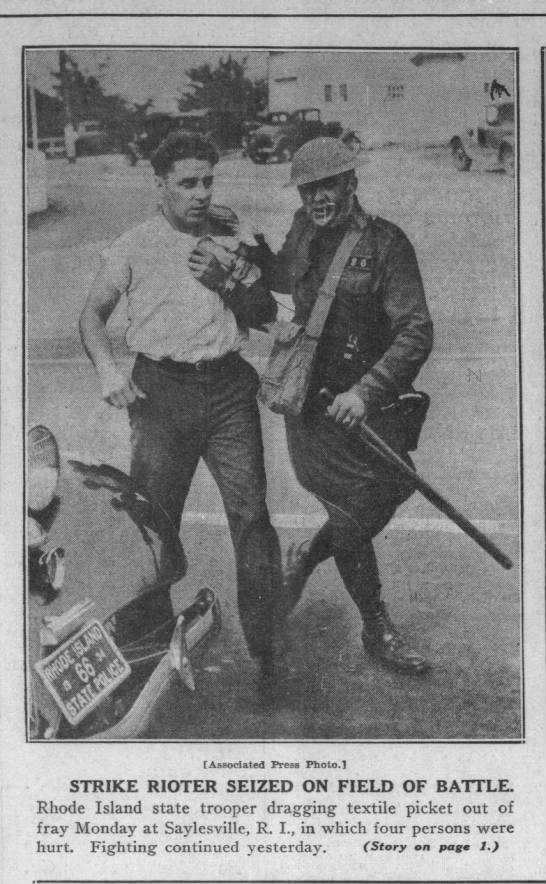

On Friday, September 7, things took a violent turn. The “Deputy Sheriffs” and security forces, whom had little to no law enforcement training, guarded the bleacheries as workers for the night shift changed. Strikers, often referred to in newspaper articles as “boys,” began to hurl rocks and stones at the bleachery-hired security forces. The leader of the security forces, Herman Paster, brandishing a revolver, admonished, “You’ll get this [revolver] if you don’t stop that.” A lone voice from crowd proclaimed, “We can take it.” Chaos erupted into a mangled mess of stone throwing, swinging riot sticks, and water shot from a fire hose at 200 pounds of pressure. Four were left injured from the melee.

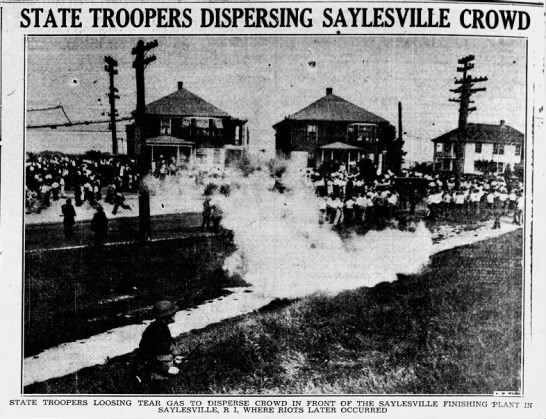

Tensions worsened as the State Police arrived and established a defensive line along Walker and Lonsdale Streets. With barbed wire strung and machine gun mounts in place, Saylesville resembled a World War I battlefield. This was only exacerbated by the arrival of the National Guard.

Around 10:00 P.M. on the evening of September 11th, tensions came to a head once again. Some of the protestors were pushed by the National Guardsmen from the grounds of St. Mathieu’s Church (today, Holy Ghost) and into the Moshassuck Cemetery. By 2:00 A.M., 300 picketers, mostly described as women and youths, stood their ground in this place meant for peaceful repose, but the scene was anything but peaceful. One woman, described in newspaper accounts, as the “woman in green,” was particularly noted for her incendiary shouts and actions. She was later identified as Rita Brouillette.

The Girl

Rita Brouillette captured my imagination immediately as I was researching for this tour. Who was she? Why was Rita, a 16-year-old girl, getting arrested as part of a textile worker strike? And what made her stand out in a crowd of hundreds of fellow protestors? As I came to learn, Rita’s life was troubling at best, but I believe her story is emblematic of the issue at hand.1

The youngest of eight living children, Rita lived with her family at 16 Aetna Street (just a few blocks away from the Sayles’ Bleacheries). In census records she is listed as unemployed. Her father worked at the Sayles’ Bleacheries and few of her older siblings held jobs in nearby textile facilities. At the time of her arrest, her soon-to-be husband, Louis Mona, ten years her senior, bailed her out. The two would be married the following month after the incident in the Moshassuck Cemetery. It is noteworthy that Louis was also a textile worker in a nearby mill. Their marriage seemed turbulent, and they separated a few years later. Rita would be buried under her maiden name.

Rita’s life was not easy. Constantly moving across the country in the years after 1934, she never seemed to have settled long in one place. By the time of her death, she was back in Rhode Island with family. As a youth, living in the shadow of the bleachery would have taken its toll. The smell, the chemicals, and the drone of the mill and its machinery would have worn on the body and soul. Her family and her boyfriend worked in the textile industry. There is no doubt her family and lover were feeling the pinch of the Great Depression and the difficulties associated with the textile industry at that time.

When interviewed by a local paper, Rita claimed she did it because “She was just having fun.” I tend to think there was much more to it than that. Maybe Rita, moved by youthful altruism, joined the ranks of her neighbors who endured similar experiences to her own family. Maybe these “kids” saw the pain in their parent’s eyes as they worried about keeping food on the table amidst the Depression. Maybe they saw the stress in older sibling’s or friend’s eyes when they were informed they were being let go. Maybe, like an 18-year-old Charles Goroynski, who would tragically die as a result of these events, they felt the weight of supporting a family and younger siblings. Goroynski, of Central Falls, was listed as the sole breadwinner for eight siblings and his mother. Maybe they were just kids looking for fun. Or, maybe, they were fighting back against the aloofness and corruption of the people who signed their paychecks. Maybe that’s what led Rita Brouillette to throw that stone.

In dawn’s early light, the situation only worsened. As Saylesville and the Moshassuck Cemetery became more of a war zone, things took a deadly turn. Nervous Guardsmen, amid a hail of rocks, bricks, and other objects intended to inflict harm, let a lethal volley rip through the headstones of the cemetery. One Guardsman, William Castaldi, was struck in the head with a flowerpot launched from a makeshift slingshot. Several Guardsmen opened fire indiscriminately. The protestors began to dive behind headstones for cover. Three were seriously wounded; Nicholas Gravello was shot in the arm (22 years old from Pawtucket), Charles Goroynski was shot in the stomach (18 years old from Central Falls), and William Blackwood was shot in the head (44 years old from Pawtucket). Goroynski and Blackwood would die of their wounds.

Immediately, leadership at the Sayles’ Bleacheries and Governor Green tried to cite “outside agitators” as causing these events. The communist party in Rhode Island was also blamed. All three of those wounded and the dozens arrested during the protest were locals, living in the surrounding communities, and all were employed or formerly employed in textiles (Blackwood was an unemployed weaver at the time of his death). True, very few of the strikers worked at the Sayles’ Bleacheries, but most were textile workers who lived within the general vicinity and surrounding communities of the bleacheries. They may not have worked at the Bleacheries, but they were people who suffered at the hands of the textile industry of which Sayles’ Bleacheries was a part.

During an interview conducted 39 years later, Kathryn McGovern of Central Falls described the events this way: “It was just like a war, it was at Saylesville… You couldn’t even breathe, they [the National Guard] had bombs… tear bombs and you couldn’t breathe… it looked just like a war.” It might not have been a war, but the sleepy cemetery and its surroundings had certainly become a battleground.

J. Hendrickson

The Stone

A headstone with an unusual story stands amid the Jewish plot of the Moshassuck Cemetery. In the 1870s, the Congregation of the Sons of David purchased the land as a place for the mortal remains of their families. This particular headstone marks the grave of Yosef Shaul Rabinowit, a Rabbi and educator. Two bullet holes are visible in the stone: a tangible reminder of the violence within the cemetery in September 1934.

The engraving on the stone starts with a simple line from the Torah, “Stone shall cry from a wall!”2 This most likely comes from a passage from the book of Habakkuk, which references the forced labor the Babylonians inflicted on the Jewish people in constructing buildings in their cities. Written millennia before the Saylesville massacre, this line offers a prophet’s damning criticism of a different political system. Across time, workers have cried out in pain when pushed too far. The lines in this stone, etched for posterity, bring these cries to life. The poetic, haunting line takes on new meaning with knowledge of the massacre.

When considering the conditions experienced by Jewish people across the world in the 1930s and what was to come in the 1940s, two bullet holes piercing this already painful plea is ironic. Also, when considering the plight of those protestors, many of whom were laborers in the textile industry, as they dove behind the stones evading messengers of death, is chilling. Perhaps this stone does wail not just in memory of Rabbi Yosef and the plight of the Jewish people through the ages, but also to the memory of Goroynski and Blackwood whose lives were lost during the Saylesville Massacre.

Back to a cold March evening in 1770, with a group of colonial protestors hurling snowballs, rocks, and insults at their own military forces. Five individuals died that evening, and this nation took another bloody step towards independence. The Boston Massacre is held up as an important event and moment of protest.

What is the place of protest in a civil society? What happens when protests turn violent, or protestors attack the very institutions we hold dear? As we commemorate America250, we as a nation must continue to investigate what a government deriving its authority from the consent of the governed even means.

Language is important when we consider memories of violence. We call things by particular names: the Boston Massacre, the Saylesville Massacre. But these events are far more complex than just words on a page. Individuals like Crispus Attucks, a self-liberated person and first casualty of the Boston Massacre, or Rita Brouillette of Saylesville notoriety, attest to that. Brouillette and other local youths experienced first-hand the stress and worry of working in the textile industry during the Great Depression. Were they communists or were they just fighting to survive? Was this a massacre or a fight?

Memories can be used to vilify or glorify; to incite or to pacify. Memories of critical events, like what happened in Saylesville in September 1934, paint a very different picture than the one that hangs on the wall of my office. These memories are a pivotal piece to helping us understand our own lives. The events in Saylesville beg a larger question: what do you care so deeply about you would be willing to risk your job, freedom, your possessions, or even your own life for? What would lead you to throw a stone?

“Stone shall cry from a wall!”

1) I would like to especially thank my colleague, Allison Horrocks. When Rita's story first caught my imagination, Allison willing jumped head first into census records, newspaper clippings, and other materials. Without her diligence and researching prowess, this largely unknown story of Rita Brouillette would have remained uncovered. Thank you, Allison, for bringing Rita's story to life, and for providing us with new knowledge on a long misinterpreted individual.

2) Special thanks to Dr. Samantha Vinokor-Meinrath who is a Jewish Educator, and graciously translated the inscription of Rabbi Yosef Rabinowit's headstone. This translation provided a poignant reminder of the pain suffered by the Jewish people through the millenia and a fitting reminder of the plight of working class peoples here in the United States. I'm deeply indebted to Dr. Vinokor-Meinrath's skills as an interpreter. The translation provided a new layer to the story which has been unknown, and that new layer of discovery has allowed for a more complete story.