Last updated: July 18, 2025

Article

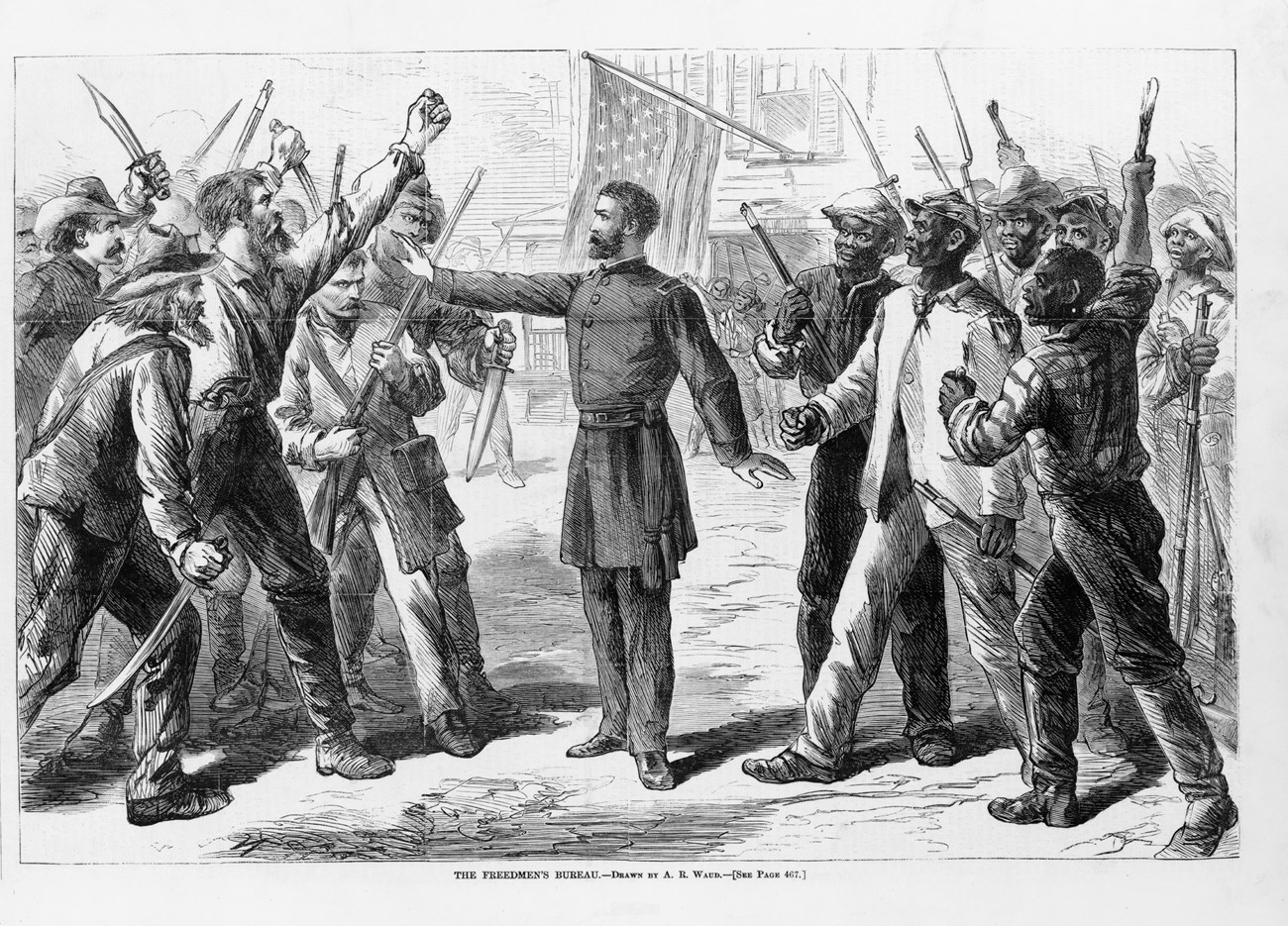

The Rise and Fall of the Freedmen's Bureau

“No sooner had Northern armies touched Southern soil than this old question, newly guised, sprang from the earth, — What shall be done with slaves?”

Library of Congress

With the outbreak of the US Civil War, the need to aid the formerly enslaved individuals that made their way to the Union lines became apparent to the US Government. “No sooner had the armies, east and west, penetrated Virginia and Tennessee than fugitive slaves appeared within their lines. They came at night, when the flickering camp fires of the blue hosts shone like vast unsteady stars along the black horizon…”1 While President Abraham Lincoln gave the authority to military commanders to render aid, and abolitionist aid societies sprang up in assistance to these needs, it was apparent that a more structured and efficient process to offer aid to the formerly enslaved was needed.

With the declaration of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Congressman Thomas D. Elliot of Massachusetts introduced a bill to establish a federal program to oversee the transition of the freedmen from bondage to freedom. Although the bill originally failed to make it out of committee, Elliot reintroduced the bill in December of 1863. This time the bill passed a narrow House vote of 69-67. After ten months of Senate debate and almost eighteen months after its inception, the bill was passed in March of 1865. Officially called the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands it would be more familiarly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The Act did not really outline the scope or programs to be offered by the new bureau as much as it outlined the structure of the organization and its place within the War Department. It did authorize the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to, “direct such issues of provisions, clothing, and fuel, as he may deem needful for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children.”2 It also gave guidance on General William T. Sherman’s Field order 15, stating that, “…to every male citizen, whether refugee or freedman, as aforesaid, there shall be assigned not more than forty acres of such land, and the person to whom it was so assigned shall be protected in the use and enjoyment of the land for the term of three years at an annual rent not exceeding six per centum upon the value of such land.”3 The Act was originally approved for a one year period.

Library of Congress

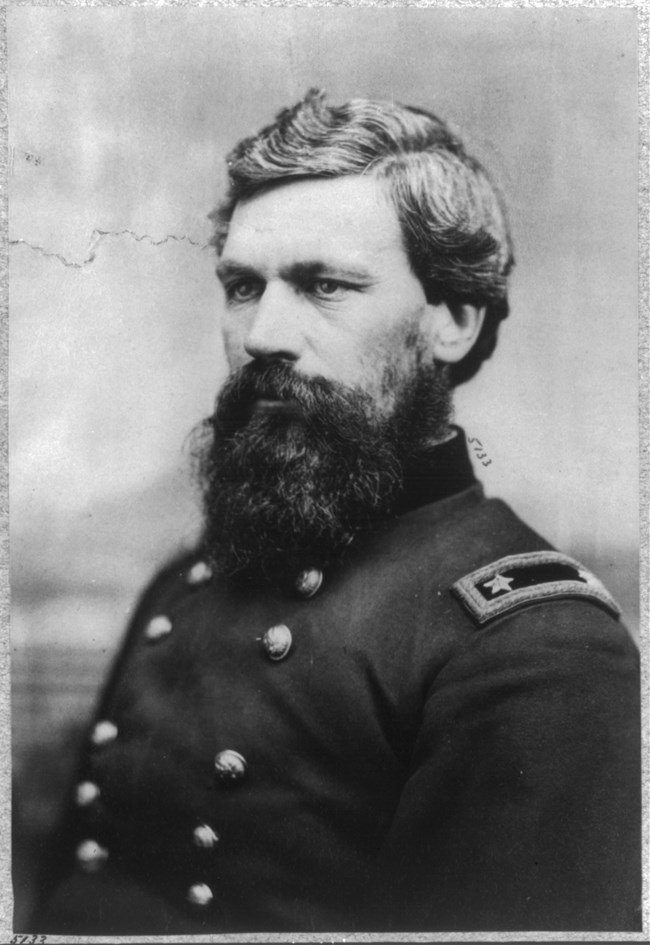

General Oliver O. Howard was appointed as the first Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Act established ten Assistant Commissioners to serve at the state level, and the use of Sub-assistants to serve at the city level. In his 2nd Circular Order, Howard outlined his three-tier approach to aid the Freedmen. The three areas of focus were: the supervision of abandoned lands, creating a system of compensated labor, and the creation and operation of educational programs.4 The order “...entrusted the supervision of abandoned lands, and the control of all subjects relating to refugees and freedmen…”5 to each state Commissioner. Although the bureau was funded by the US Treasury, it relied heavily on the work of benevolent aid societies in the North.

Following the initial year of the Freedmen’s Bureau, critics of the program began to emerge. Most of which were former Confederate Democrats, falsely claiming the bureau interfered with the rebuilding and race relations between freedmen and whites in the South. In a report to Howard, Assistant Commissioner Eliphalet Whittlesey, a Chaplin from the 19th Maine Volunteer Infantry, wrote in response to the criticism, “The real work of the Bureau which has taxed the energy and patience of all connected ... they pass unnoticed and direct their energy to the discovery of faults.... They make no distinct and open charges, but content themselves with insinuations and conjectures.”6 He also went on to explain successes the bureau had accomplished in land distribution, employment, and education. Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull introduced the bill to extend the bureau past its original legislation; after passing through Congress, it was vetoed by President Johnson. Like many of the President’s Reconstruction vetoes, it was overturned, and the Freedmen’s Bureau was authorized for another two years.

Library of Congress

This time the Act clearly defined the Bureau’s purpose. The Act contained new language “That the supervision and care of said bureau shall extend to all loyal refugees and freedmen, so far as the same shall be necessary to enable them as speedily as practicable to become self-supporting citizens of the United States…”7 With the passage of the Military Reconstruction Act in 1867, the bureau was placed under direct authority of the military commanders of the five newly created military occupation districts. W.E.B Du Bois wrote,

“The government of the unreconstructed South was thus put very largely in the hands of the Freedmen's Bureau… It was thus that the Freedmen's Bureau became a full-fledged government of men. It made laws, executed them and interpreted them; it laid and collected taxes, defined and punished crime, maintained and used military force, and dictated such measures as it thought necessary and proper for the accomplishment of its varied ends.”8

Library of Congress

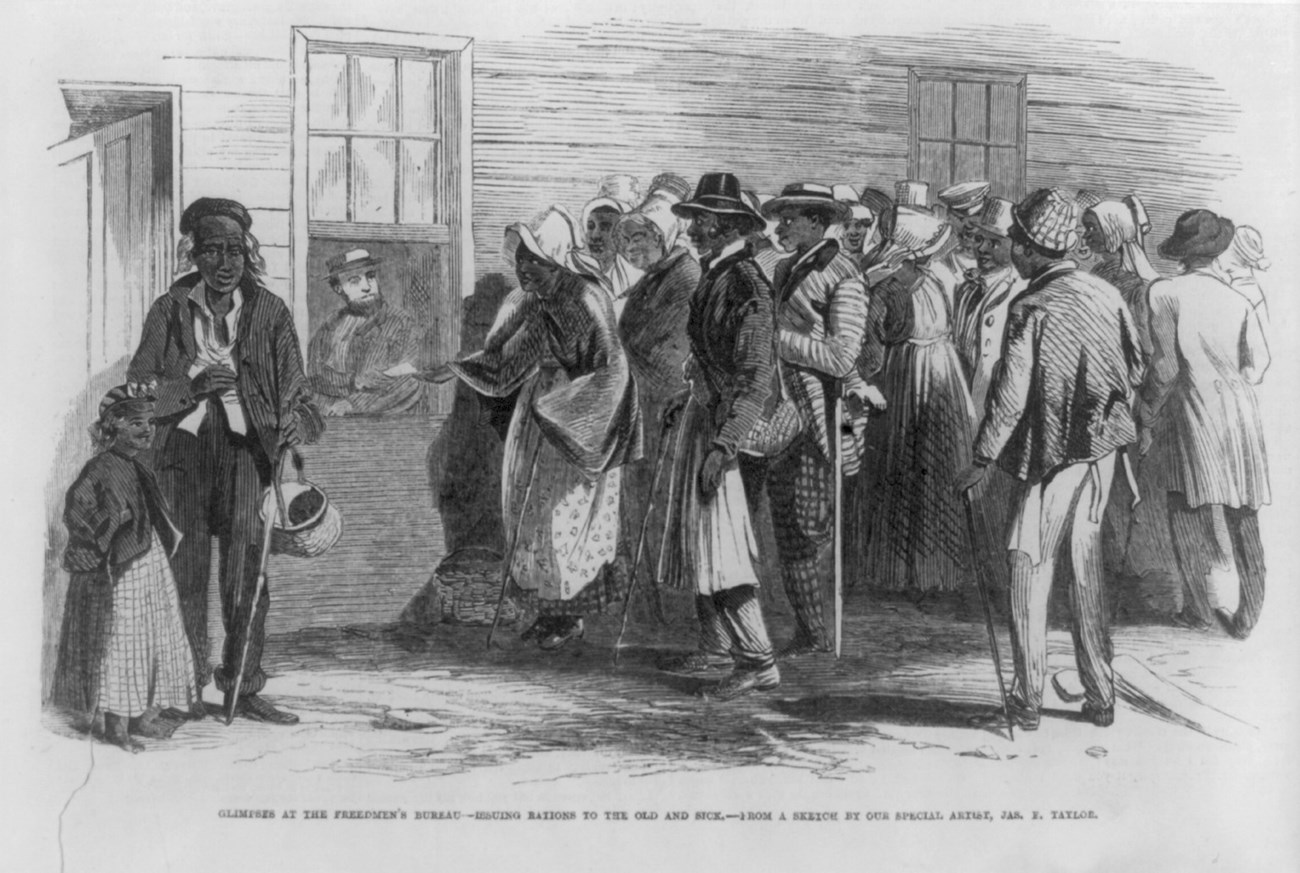

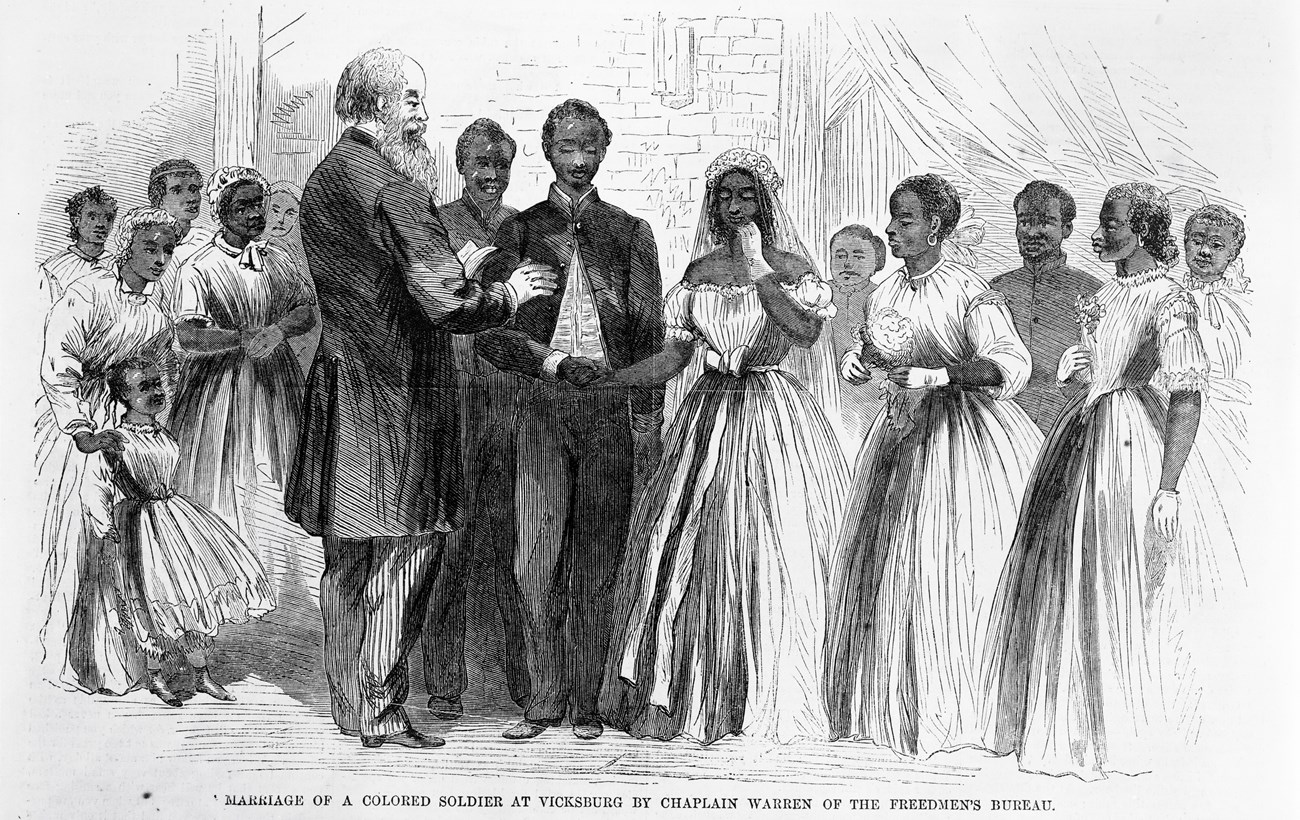

With 627 field offices in 433 counties the Freedmen’s Bureau extended relief to refugees and freedmen across the Southern States. From 1865 to 1870 the Freedmen’s Bureau provided over fifteen million rations to destitute whites and the formerly enslaved. The bureau established refugee camps, provided clothing, medical care, legal services, and even helped the freedmen legally get married. Although the bureau provided over 400,000 acres of land to about 10,000 families of freed people, only a sixth of that land would remain in the hands of Black families. Education was seen as one of the lasting accomplishments of the bureau. By 1870, the Freedmen’s Bureau supported over 1,500 schools educating over 100,000 pupils. With the help of the Second Morrill Act, it created higher education opportunities for Black Americans. As well as the creation of a state funded public education system. Over six million dollars were spent over a five-year period of the Freedmen’s Bureau for the purpose of educating the Freedmen. W.E.B. Du Bois said of this, “The greatest success of the Freedmen's Bureau lay in the planting of the free school among Negroes.”10

NPS/Elizabeth Hyde Botume Collection

By 1869, Congress cut most of the funding for the bureau, and the Freedmen’s Bureau began shutting offices and cutting staff, leaving only the educational programs intact. Without support or adequate funding these programs began to dwindle until the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands was discontinued in June 1872. With a rise in racial violence in the South and the collapse of the Freedmen’s Bank in 1874, Black Americans were left with little to no protection or economic promise in a land once again under the control of their former enslavers.

Resources

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Atlantic, March 1901.

- Congress.gov. "Text - H.R.698 - 38th Congress (1863-1865): A Bill To establish, in the War Department, a Bureau for the Relief of Freedmen and Refugees." July 16, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/38th-congress/house-bill/698/text.

- Ibid

- Oliver O. Howard, “Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, Circular No. 2,” Remaking Virginia: Transformation Through Emancipation, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.virginiamemory.com/online-exhibitions/items/show/509.

- Ibid

- Eliphalet Whittlesey report to Oliver Otis Howard, Executive documents printed by order of the House of Representatives during the first session of the thirty-ninth Congress, 1865-'66, Washington DC, Government Printing Office, 1866, pg. 20-21, https://archive.org/details/executivedocumenunit/mode/2up.

- Congress.gov. "Text - H.R.613 - 39th Congress (1865-1867): A Bill To continue in force and to amend an act entitled ''An act to establish a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees,'' and for other purposes." July 16, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/39th-congress/house-bill/613/text.

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Atlantic, March 1901.

- Ibid

Other Resources

-

Jon C. Rogowski, Reconstruction and the State: The Political and Economic Consequences of the Freedmen’s Bureau, August 20, 2018, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/rogowski/files/freedmens_bureau_0.pdf.

-

Ira C. Colby, “The Freedmen’s Bureau: From Social Welfare to Segregation,” Phylon, 3, 46, no. 3 (1985): 219–30.