Last updated: April 10, 2024

Article

The Return of the Horseshoe Crabs!

Photo/NPS

Written by Charlotte Hohman, NPS

When traveling to Provincetown on Route 6, one drives across a narrow strip of land bordered to the east by a shallow lagoon called East Harbor. Below the relatively calm surface dotted by seabirds, this lagoon hides a bizarre, ancient animal relied upon by both humans, birds, and marine organisms in its ecosystem.

East Harbor was naturally connected to Cape Cod Bay hundreds of years ago but was diked off and separated from the bay when the railroad to Provincetown was built in 1868. The marine life was killed off as the harbor was eventually transformed into a freshwater lake, which was eventually renamed to Pilgrim Lake. This lake, however, was not representative of a healthy ecosystem. The water quality declined, and in 2001, multiple fish kills and insect outbreaks occurred.

Photo/NPS

In response to these issues, in 2002, a partnership was formed between the Cape Cod National Seashore and the Town of Truro to allow saltwater tides back into the lake by building a culvert to reconnect the lake to Cape Cod Bay. As a result of this reconnection, the water quality improved as the lagoon flushed with the daily tides and became brackish once again. Marine creatures returned as the salinity increased, and the lake was renamed back to East Harbor.

The amount and diversity of sea life that would return was not clear, given that the only way into East Harbor would be through a narrow 700-foot-long tunnel. However, in 2010, Cape Cod National Seashore natural resources staff noticed the molted shells, or carapaces, of horseshoe crabs on the beach at East Harbor.

Photo/Delaware Ornithological Society

Horseshoe crabs are important to the local economy, as they serve as bait for whelk fishing (a type of marine snail). They are also harvested by biomedical companies for their blood, which contains Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL), an important ingredient necessary to creating safe vaccines and implantable medical devices. To date, all vaccines and implantable devices are tested with LAL from horseshoe crab blood for their safe use in humans. There is no approved synthetic substitute, though much work is being done to approve an alternative. These organisms also fulfill important roles in their ecosystems outside of human needs. Their eggs serve as nutritious food for migrating shorebirds like the federally threatened red knot, and the adult horseshoe crabs are important coastal predators that keep populations of their prey, like worms and mollusks, in check.

Photo/Alton Dooley

Horseshoe crabs are incredibly ancient animals, first appearing around 440 million years ago. These magnificent yet bizarre creatures are not crabs, but rather, closely related to arachnids such as spiders and scorpions. They are the last of their lineage and have survived all five mass extinction events! But their strong record of survivorship does not give us any guarantee that they will be here permanently. Populations are declining in many places due to overharvesting and habitat degradation, which is concerning for the stability of their ecosystems and the future of the species. Luckily, Cape Cod National Seashore is a protected area, meaning that the horseshoe crabs cannot be harvested here.

Photo/NPS

Nevertheless, their presence in East Harbor was somewhat surprising, given that the only way in is through the long culvert. When the tide is high, the horseshoe crabs in Cape Cod Bay can crawl into the culvert, and then make the 700-foot trek to get into East Harbor.

After evidence of horseshoe crabs began showing up, Cape Cod National Seashore scientists realized that we needed to monitor them to understand their population in East Harbor. Understanding how the horseshoe crabs use the habitat in the park could help shed light on how their populations might behave when external threats like harvesting are eliminated. This was the catalyst for a two-year tagging project undertaken by park staff and interns, in collaboration with researchers and graduate students from Antioch University of New England in Keene, NH.

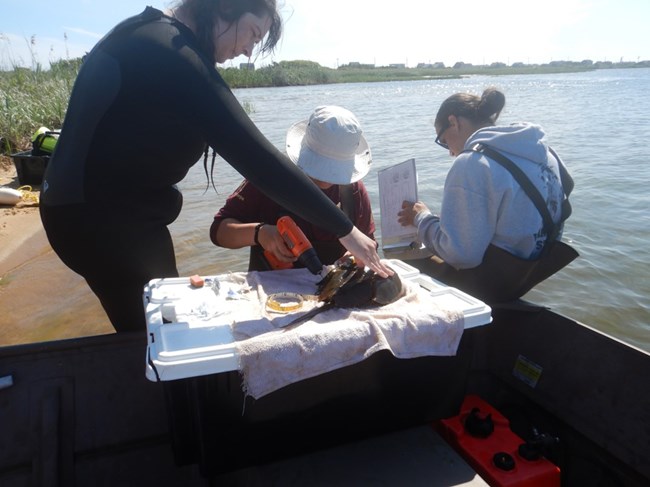

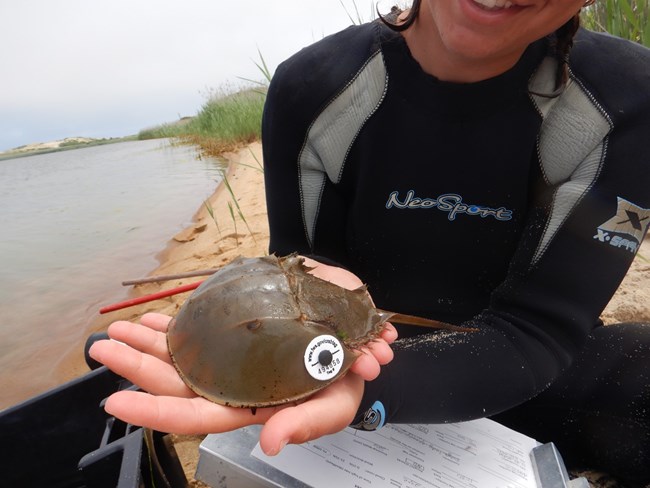

Photo/NPS

The main questions of the study focused on the size of the population in East Harbor, how they use the habitat throughout their lives, and if horseshoe crabs are actively going in and out of the system. To do this, the natural resource team spent many days traipsing through the shallows searching for horseshoe crabs. Upon capture, information about the horseshoe crabs’ size, sex, and mating status would be recorded, as well as the environmental conditions at the time of capture and the GPS location. The horseshoe crabs would then be tagged with different kinds of trackers depending on their age and released.

So far, the preliminary project results show a large population of horseshoe crabs in East Harbor—around 890 individuals were tagged! Cape Cod National Seashore, Aquatic Ecologist, Dr. Sophia Fox, shared that when the project began, she thought they would be lucky to find 200 horseshoe crabs, and their abundance in East Harbor has been shocking. All life stages from larvae to adults have been found. Juveniles mostly hung out in the northeast area of the system, while most adults and mating occurred on the southwest side. Based on radio tracking data, the female horseshoe crabs were found throughout the lagoon, and despite the length of the culvert, researchers found that at least some of the horseshoe crabs moved out of East Harbor and into the adjacent Cape Cod Bay. While the individuals living in this protected environment weren’t different from other populations in terms of their body size, interestingly, the horseshoe crabs in East Harbor seem to have a longer mating season and were found in male/female pairs well into October.

Map/NPS

The success of horseshoe crabs in East Harbor speaks positively about their ability to rebound and thrive in protected areas, and the monitoring of the East Harbor horseshoe crabs will continue at Cape Cod National Seashore. Through studies like this and the protection from threats afforded by the National Seashore, we can help ensure that this unique group of survivors can continue to scuttle around the ocean floor for many more millennia to come.

Photo/PBS