Last updated: August 27, 2020

Article

The Remarkable Roscoe, Part II

Library of Congress

If Roscoe Conkling’s support of Abraham Lincoln and opposition to Andrew Johnson in the 1860s grew out of an understanding of the needs of the entire country, then it is also clear that his later relations with Grant, Hayes, and Garfield were colored by his preoccupation with the local political machine he sought to preserve. His contemporaries recognized that he was intelligent and capable.

A one-time ally, railroad executive Chauncey Depew, made the point in retrospect. “Roscoe Conkling was created by nature for a great career.” That he wasted his talents “was entirely his own fault. Physically he was the handsomest man of his time. His mental equipment nearly approached genius… His oratorical gifts were of the highest order, and he was a debater of rare power and resources. But his intolerable egotism deprived him of the vision necessary for supreme leadership…. [H]is wonderful gifts were wholly devoted to partisan discussions and local issues.”

The shift in his attention away from national needs toward an increasingly narrow and self-interested point of view manifested itself during the Grant administration. From 1869 onward, the junior Senator from New York was Grant’s most steadfast supporter. In turn, Grant made it possible for Conkling to become the dominant political figure in New York State Republican politics.

One of Grant’s early foreign policy initiatives was the annexation of San Domingo (today’s Dominican Republic). Grant’s objectives were many: to establish an American naval station in this island nation, to provide trade opportunities for the Dominicans, to offer “the protection of our free institutions and laws, our progress and civilization,” and to encourage recently freed blacks to emigrate. This last goal might have resulted in the elimination of the race issue in the U.S.; at the least it might have forced white Southerners to treat black Southerners more fairly – at the risk of losing black labor. When Senate Foreign Relations Chairman, Charles Sumner, objected, it was Conkling who, at Grant’s request, took the lead in having Sumner removed from his post.

Conkling’s support of Grant strengthened their bond. Happily for Conkling, Grant’s relationship with New York’s other Senator, Reuben Fenton, was not good. Fenton fawned over Grant, which the latter did not like. Conkling, by contrast, was always respectful, yet stuck to his guns when challenged. Grant liked that!

When it was time to appoint a new Collector of the Port of New York, Grant’s choice favored Conkling rather than Fenton. The Collectorship was the most important appointive post in the nation. More imports came into New York than into any other port in the nation. The job of Collector carried many responsibilities and perks, and presented many opportunities to preside over a workforce that would be loyal to a man who knew how to build a political machine. Conkling and Fenton were rivals to be that man. Each man wanted to dominate New York’s Republican Party. The two men who had the best chance for being appointed were Thomas Murphy and William Robertson. Robertson was an ally of Senator Fenton. Murphy was more of an independent. Conkling threw his support to Murphy. After Grant appointed Murphy, Conkling’s authority in New York increased as Fenton’s withered.

However, Conkling’s rise did not help Republicans nationwide. Historically, a President’s party tends to lose seats in midterm elections. In addition, there was dissatisfaction with some Grant policies and appointments. Consequently, Republican majorities in the Congress were reduced after the 1870 midterm election.

Wkipedia.com

Despite the President’s declining prestige, Conkling defended Grant unstintingly. To a correspondent he wrote, “He has made a better President than you and I, when we voted for him, had any right to expect…” Conkling reminded an audience at Cooper Union of Grant’s storied service to the nation. Grant was “honest, brave, and modest, and proved by his translucent deeds to be endowed with genius, common sense and moral qualities adequate to our greatest affairs…” He had “snatched our nationality and our cause from despair, and bore them on his shield through the flame of battle” To a nineteenth century audience, Conkling’s vivid descriptions of Grant most certainly struck a chord. One can only imagine how his physical presence and voice reinforced the sentiments he expressed.

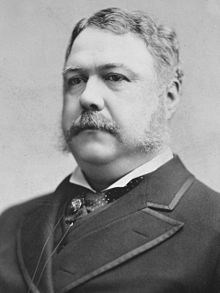

Two developments in 1871 and 1872 illustrate Conkling‘s growing authority, and the political alliances that would in time undo that authority. Late in 1871, Thomas Murphy resigned as Collector of the Port of New York. Conkling recommended the appointment of Chester Alan Arthur as the new Collector. Grant made the appointment.

Arthur was a good choice. He was “honest, efficient and courteous, and unlike Tom Murphy he had none of the air of the party hack.” He was also Conkling’s man. Chester Arthur’s appointment, and the defeat of William Robertson for the gubernatorial nomination in the summer of 1872, outlined the contours of Conkling’s political actions for the next several years. William Robertson blamed Senator Conkling for his defeat. Meanwhile, Chester Arthur became a kind of lightning rod for Conkling. In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes would attack Conkling’s power in New York by firing Arthur. In 1880, Robertson’s actions would assault Conkling’s authority in the Republican Party. In time, their conflicting personalities and goals would clash again – and again.

Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center

Conkling was steadfast and influential during Grant’s second term. At its beginning, in 1873, a financial panic struck the nation. It was devastating. One response to it among some members of Congress was a bill to issue more paper money so that Americans could pay their debts. Conkling called this proposal “a falsehood and a fraud. It can never be true, and therefore it can never be right or safe.” When the Inflation Act of 1874 was passed, Conkling urged Grant to veto it. After some indecision, Grant followed Conkling’s advice. (James Garfield held the same view of paper money, that it was dishonest and bad for the economy.)

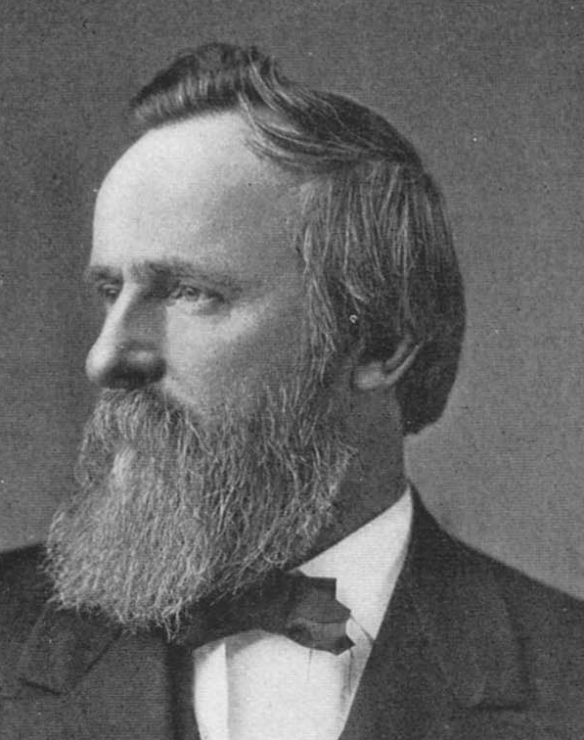

The other major service that Conkling performed for the nation in this period came at the end of Grant’s term. It involved the disputed election of 1876. Was Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican nominee, to succeed Grant, or was it to be the Democrat, Governor Samuel Tilden of New York? Nationwide, Tilden had won a quarter million more popular votes than Hayes. But in three Southern states, (Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina) there were charges of fraud and suppression of the black vote. Who had actually won in these states, and how were their electoral votes to be awarded? In all three states, both parties were determined to send their electors to Washington. There was also a disputed elector in Oregon. It was a quandary for the entire country.

To resolve the matter, President Grant favored creating a Congressional Commission that would review the states’ votes and recognize the appropriate electors. Again serving as President Grant’s strongest ally in the Congress, Senator Conkling led the effort that created the Electoral Commission of 1877. The measure was seen as unconstitutional by many, including James Garfield, because it gave Congress a hitherto unwarranted part in the election of a president. The commission bill passed, however, and the Commission that was created (Garfield was a member but Conkling was not) decided the election for Hayes. David Jordan called it Conkling’s finest moment. Perhaps so, but whether it was his finest moment in behalf of the nation, or in behalf of his party, is an open question.

Ironically, the Republican Conkling believed that the Democrat Tilden had carried Florida and Louisiana, and therefore the election – and he said so publicly. Moreover, Conkling’s lack of enthusiasm for Hayes may have caused the Republican to lose New York. After Hayes was declared the winner, Conkling referred to Hayes as “Rutherfraud B. Hayes,” and “His Fraudulency.”

What transpired next was a mixture of reform-minded idealism and political payback on the part of Hayes, with Conkling doing all he could to preserve his political machine in New York. On the one hand, Hayes the idealist believed that political work done on federal work time was unethical. On the other hand, Hayes the politician, and his Secretary of State, New Yorker William Evarts, wanted to create a political base favorable to the new administration.

Mixing the ideal with the political, Hayes appointed a commission to investigate several major port cities. Among its recommendations were changes at the Port of New York. In June Hayes attempted to replace Conkling’s allies, Collector Chester Arthur and Naval Officer Alonzo Cornell, with recess appointments. This action failed to achieve the desired result, but in 1879, Edwin Merritt and Silas Burt were confirmed by the Senate as permanent replacements for Arthur and Cornell. The fight over the Collectorship dominated and poisoned political relations between Hayes and Conkling.

(Check back soon for the conclusion of “The Remarkable Roscoe”!)

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, Jame A. Garfield National Historic Site, July 2013 for the Garfield Observer.