Last updated: August 27, 2020

Article

The Remarkable Roscoe: Friend and Nemesis of Presidents (Part I)

Wikipedia.com

Arguably, the greatest adversary James A. Garfield ever encountered in his national political career was the New York senator and political boss, Roscoe Conkling. Conkling, a man who thrived on battling perceived enemies, was also one of the most colorful political figures of Reconstruction and the Gilded Age. Two descriptions of Conkling, one modern and one contemporary, make the point well. David M. Jordan, Conkling’s most recent biographer, captured an unforgettable presence and a most striking personality:

“‘Lord Roscoe,’ many called him, and he carried himself like a member of the higher peerage. Roscoe Conkling steps from the pages of history angry, haughty, larger than life. Although he was vindictive and overbearing, he was handsome, intelligent, and capable of orating for hours at a time without losing either a word of his memorized speech or a listener; gaudy as a peacock, he makes the political leaders of our era pale into shadows in comparison. He was not a pleasant man, but he stirred strong emotions, and he had a considerable impact on American history.”

Politico.com

Less charitably, Conkling’s bete noire in politics, James G. Blaine, delivered a salvo at Conkling on the floor of the House on April 30, 1866, that made the two men adversaries for the rest of their careers. Sneered Blaine after several exchanges between the two:

“The contempt of that large-minded gentleman is so wilting; his haughty disdain, his grandiloquent swell, his majestic, super-eminent, overpowering turkey-gobbler strut has been so crushing to myself and all the members of this House that I know it was an act of the greatest temerity for me to venture upon a controversy with him.”

These withering remarks were aimed at a dynamic, very influential political personality, someone who was taken very seriously in his day. The Conkling-Blaine rivalry dominated Republican Party politics throughout the late 1860s, 1870s and early 1880s.

Roscoe Conkling was born on October 30, 1829 (just weeks after his future political acolyte, Chester Alan Arthur) in Albany, New York. Little is known of his earliest years, but biographer Jordan notes that by age fourteen, young Roscoe’s interest in politics had taken root. At age sixteen, he was studying law in Utica. At twenty, he was committed to the abolition of slavery. In this commitment, he had something in common with James A. Garfield, whose own antislavery sentiments were just beginning to emerge at this time.

Jackdaw Cartoons

The future Senator from New York was physically impressive. He stood six feet, three inches tall, was “erect and muscular,” and blond. He sported a “Hyperion” curl on his forehead that was the delight of political cartoonists; at a time when the sartorial standard for men was black, Conkling made an elegant figure, sporting colorful vests of yellow or lavender and light-colored trousers. He was an advocate of physical fitness, a skilled and avid horseman and an enthusiast for boxing.

Conkling was also blessed with intelligence and physical appeal. Though married to Julia Seymour in 1855 (she the sister of Horatio Seymour, a future governor of New York and the 1868 Democratic presidential nominee), many women found him attractive. He “exud[ed] animal vigor, even sexuality,” according to David Jordan. Altogether, the pride he took in his physical and oratorical prowess was part and parcel of his political mystique.

Like Garfield, Conkling possessed a driving need for “self-improvement.” He read a great deal – Shakespeare, Milton, Macaulay, and Byron. According to David Jordan, he possessed “a prodigious memory” by which he could “reproduce verbatim” much of what he read.

Elected to Congress in 1859, his acid tongue shortly found a target in President James Buchanan during the secession crisis of late 1860. Buchanan, he said, was “petrified by fear, or vacillating between determination and doubt, while the rebels snatched from his nerveless grasp the ensign of the Republic, and waved before his eyes the banner of secession…”

Though he had supported Seward for the 1860 Republican presidential nomination, he believed as Lincoln did, that slavery in the United States would be eventually abolished. Early in the war, he favored President Lincoln’s idea of compensated emancipation – paying slaveholders to free their slaves. Even so, Conkling was a fiscal conservative, and opposed financing the war with paper money. He was for “sound money,” that is, money backed by gold. Here was another view he shared in common with James Garfield.

For a man who descended the pages of history with the unsavory reputation of a corruptionist, Conkling was seen early in his career as “an opponent of all sorts of jobbery and corruption.” And in fact, he does not seem to have been politically corrupt. He does not appear to have benefitted financially from his political wire pulling.

Wikipedia.com

Conkling was regarded as “a consistent and warm personal friend of President Lincoln.” This was probably an exaggeration. In 1864, when Conkling was running for reelection, some local Republicans wanted another candidate. Abraham Lincoln endorsed him in a letter that read in part, “I am for the regular nominee in all cases… no one could be more satisfactory to me as the nominee in that District, than Mr. Conkling. I do not mean to say there are not others as good as he is… but I think I know him to be at least good enough. Given the divisions in the Republican Party at the time, Lincoln was choosing his words carefully.

Whether for reasons of humanity or because it was the “politically correct” stance to take, Conkling opposed the “Black Codes” of the South that restricted the employment opportunities and geographical movement of blacks. He insisted that the southern states repudiate the Confederate debt and the right to secede. He helped to write the 14th Amendment, which gave blacks citizenship. Like Garfield, he insisted that the southern states ratify the 15th amendment, which granted black men the right to vote, before they could be readmitted to the Union. To demonstrate his support for the first black member of the Senate, he made it a point to escort Mississippi Senator Blanche K. Bruce about the chamber when other white senators shied away.

Like other Republicans, Conkling became increasingly bothered by the leadership style of Andrew Johnson, and supported his impeachment. When Johnson took his national “Swing ‘Round the Circle” during the 1886 election, Conkling referred to the president as an “angry man, dizzy with the elevation to which assassination has raised him, frenzied with power and ambition…”

Conkling developed close ties with Johnson’s successor, Ulysses S. Grant. He admired Grant’s service during the war and became a loyal ally. The two men worked well together. Conkling supported Grant’s cabinet appointments, his Reconstruction policies, and the president’s efforts to annex Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) to the United States. Conkling supported Grant’s appointment of Thomas Murphy to be Collector of New York in 1870, and Grant approved Conkling’s recommendations for other New York appointments.

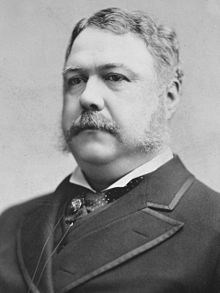

Murphy proved to be a less than scrupulous public official. In 1871 he was forced out of his position. Conkling recommended the honest, efficient, and courteous Chester Alan Arthur as his successor, and Grant made the appointment. And unlike Murphy, Chester Arthur was no party hack. He ran the port well, and through it he helped Roscoe Conkling build and maintain a political machine in New York.

Wikipedia.com

Revelations of waste and scandal during the first Grant administration led to a revolt within the party in 1872. Well-born gentlemen, newspaper editors, and politicians (in both parties, really) stressed the need to appoint government workers on the basis of merit, not political loyalties. Conkling was threatened by such talk of reform. He had built a political machine in New York based on his ability to control who received federal jobs. To him, Civil Service Reform was more properly “snivel service reform.”Concern over Grant’s administration meant that there was no chance that he would be his party’s nominee for a third term in 1876. That year’s contested nominating convention put forth Governor Rutherford B. Hayes as the Republican choice to succeed Grant. Hayes was perceived as a reformer, but Conkling was unimpressed. He dragged his feet during the campaign, and probably for that reason Hayes lost New York.

The election results were so close, and there was so much controversy over voting irregularities in the South, that the winner of the Hayes-Tilden was disputed. Conkling was a principal author of the legislation that created a Congressional commission to resolve the election. But although he was a Republican, Conkling believed that Democrat Samuel Tilden was the rightful victor. Consequently, he referred to Hayes as “Rutherfraud B.Hayes.” No love was lost between the two men.

In 1878, Hayes removed Chester Arthur from the Collectorship. The move was part reform-minded and in part payback. Hayes and his Secretary of State, New Yorker William Evarts, wanted to build a new Republican machine in the Empire State loyal to the reformers. So, the bad blood between Hayes and Conkling persisted into the 1880 election cycle.

Hayes was not a candidate for reelection, but Grant was urged to seek a third term. Though he was genuinely interested in a third term, reformers in the Republican Party were determined to prevent it. Within the New York Republican Party, State Senator William H. Robertson was a leader in the anti-Grant forces. Robertson’s maneuverings at the Republican Convention in Chicago figured large in denying Conkling’s man Grant a third presidential bid. The “beneficiary” of the deadlocked convention was of course James A. Garfield, a man closely associated with Conking’s primary adversary, President Hayes.

(“Stay tuned” for Part II, where the Conkling-Garfield dispute and Conkling’s life after politics will be discussed.)

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, June 2013 for the Garfield Observer.