Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Mary Ann Shadd Cary.

Previous: Learning from Mary Ann Shadd Cary

Article

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was a long-time advocate for African American civil rights, women’s suffrage, and temperance. Mary Ann worked as a teacher and journalist throughout her life. While living in Ontario during the 1850s, she co-founded Canada's first anti-slavery newspaper, the Provincial Freeman. Throughout the 1860s, Mary Ann attended many national and state-level conferences as part of the Colored Conventions movement. She also became a member of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In 1876, Mary Ann petitioned NWSA to include the signatures of 94 African American women in the Declaration of the Rights of Women. She founded the Colored Woman’s Progressive Franchise Association to advance voting rights for African American women in 1880. Mary Ann graduated from Howard Law School in 1883 at 60 years old. She was the second Black woman in the United States to earn a law degree. Mary Ann died from stomach cancer in 1893 and did not live to see the national expansion of women’s voting rights.

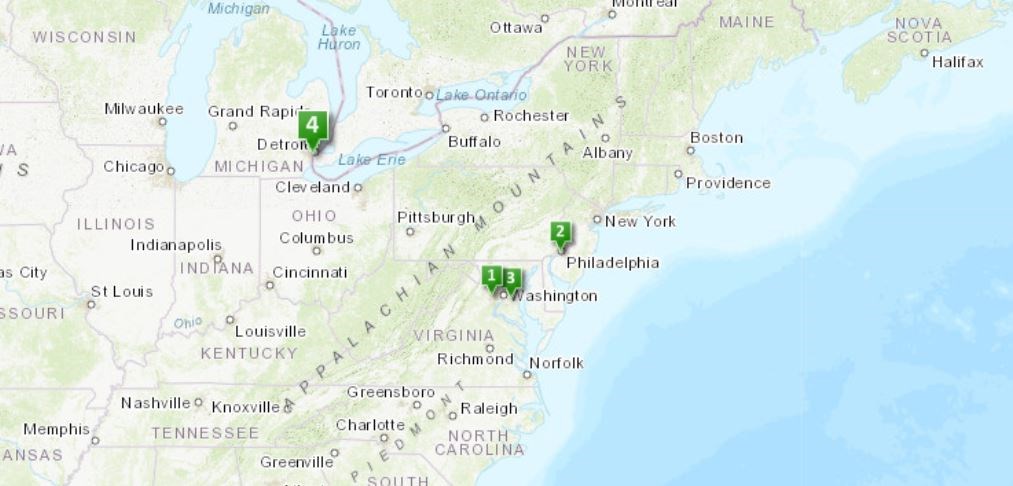

Discover the places where Cary lived, worked, and studied and gain a better understanding of how she shaped social change in 19th century America.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705860/.

The Bethel Literary and Historical Association met at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. The Association supported education and opportunity for African Americans. At meetings, members participated in discussions about racism, economic inequality, and labor rights. The Association also hosted notable speakers, like Mary Church Terrell, Booker T. Washington, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Mary Ann Shadd Cary was a regular presence at meetings and became known as a fearless debater. She often spoke out about women's rights and voting rights. In 1881, she contributed to a discussion about "eminent women of the Negro race." At another meeting, she spoke about “the Heroes of the Anti-Slavery Struggle" and her experiences before the Civil War.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/75696517/.

Philadelphia hosted the National Convention of the Free People of Color in October 1855. Delegates including Mary Ann Shadd gathered for the first day’s evening session at the Young Man’s Institute, also known as the Philadelphia City Institute. The Institute’s former site stood at 18th and Chestnut Streets in Center City West Commercial Historic District. At the convention, delegates debated over Mary Ann's membership. Her support for the emigration of free Blacks to Canada was controversial. Resorting to emigration implied that true racial equality could not be achieved in the United States. Opponents of emigration argued that free Blacks should remain to fight for the abolition of slavery and racial equality. After a vote of 38 to 23, the delegates formally accepted Mary Ann as a corresponding member. She was the sole delegate from Canada. Despite their differences over emigration, delegates found Mary Ann's speaking ability so impressive that they voted to extend her speaking time.

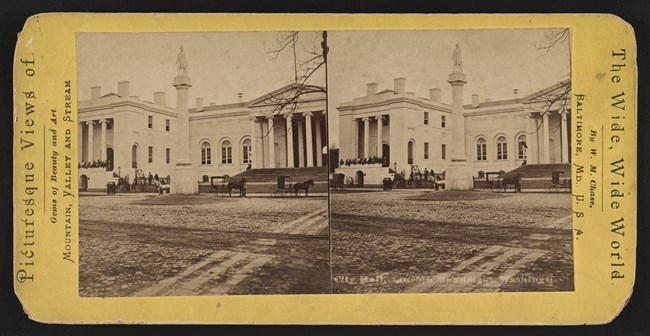

Courtesy Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017646942/

Mary Ann Shadd Cary attempted to register to vote in Washington, D.C.’s second delegate district on April 14, 1871. She presented proof of citizenship and residency before a seven-member Board of Registration at City Hall. Although Mary Ann knew two African American members of the Board, they denied her request. Five days later, Mary Ann documented the events before a notary. She claimed that the Board wrongfully obstructed her legal right to vote “pursuant to the act of Congress.” This likely referred to the Fifteenth Amendment. Ratified in 1870, this Amendment stated that voting rights could not be denied based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Mary Ann criticized the Fifteenth Amendment because it did not extend voting rights for African American women.

Photo by Andrew Jameson, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4375695

The Second Baptist Church played an important role in Detroit's African American history. Thirteen formerly enslaved people founded the church in 1836. It also served as a station on the Underground Railroad for freedom seekers headed to Canada. During the mid-1800s, the church hosted two Colored Men’s State Conventions. Mary Ann Shadd Cary attended the second convention in 1865. This convention promoted African American citizenship and voting rights. Delegates also established the Equal Rights League of Michigan. Convention proceedings report that Mary Ann declined an invitation to speak. Nevertheless, she "heartily desired to see [equality under the law] accomplished" for African Americans.

Selected Sources:

Cromwell, John W. History of the Bethel Literary and Historical Association, and Programme for the Year 1895-6. Pamphlet. Washington, D.C.: R. L. Pendleton, 1896. Library of Congress, Manuscript/Mixed Material, Mary Church Terrell Papers 1884-1962. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss425490257/.

McHenry, Elizabeth. Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Rhodes, Jane. Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1998.

National Trust for Historic Preservation. “Metropolitan AME Church.” 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. Accessed March 4, 2020. https://savingplaces.org/places/metropolitan-ame-church#.Xl8fh6hKjZs.

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Mary Ann Shadd Cary.

Previous: Learning from Mary Ann Shadd Cary

Last updated: May 6, 2021