Last updated: July 11, 2023

Article

The Natural Landscape of the White Haven Estate

National Park Service

The land at White Haven and the people who lived on it are part of a give and take process that has continued for hundreds of years. Changes to the land included tree removal, crop cultivation, livestock management, and the consumption of natural resources. These environmental practices have shaped the landscape around White Haven. By analyzing two major natural features of the property--the Little Prairie Creek watershed and the wooded acreage that surrounds the historic home--scholars can learn about the kind of relationship the people and the land at White Haven had and continue to have.

National Park Service

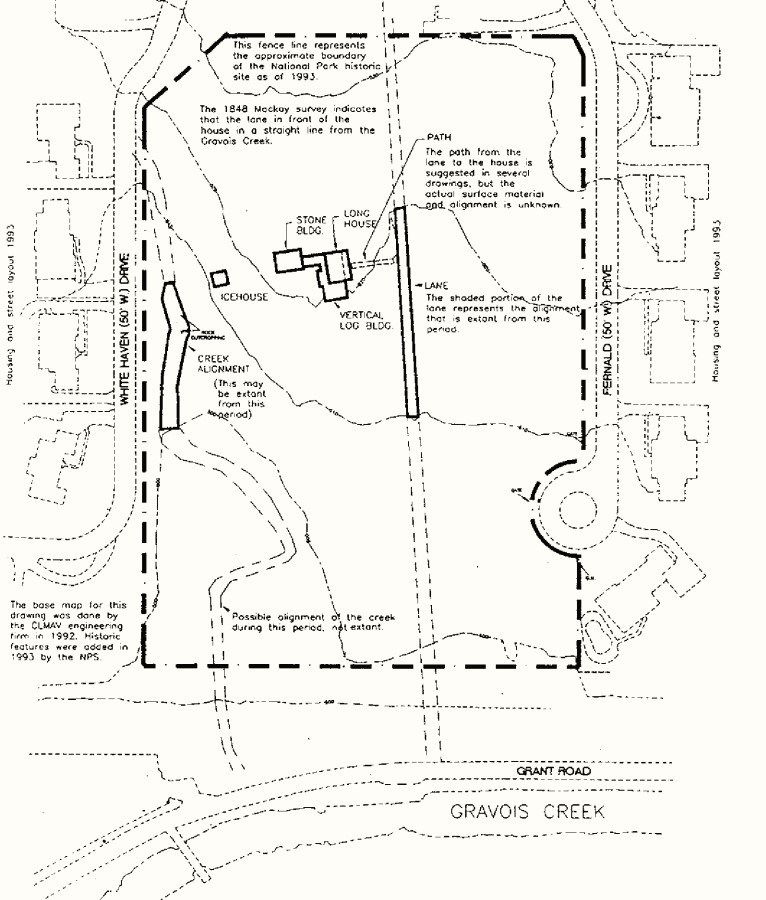

In addition to coral, there was also a spring along the creek for most of the 19th century that was located almost directly behind the main house. It is believed that a spring house was located near the present day locations of the ice and chicken houses, but by the early 20th century, all that remained were ruins as seen in a 1916 photo taken three years after the acquisition of the property by the Wenzlick family. Perhaps the most significant change to the watershed occurred during the 20th century, when the creek was realigned to more closely follow the boundary line of what would eventually become the edge of the National Park Service property. Despite the course of the creek not being altered until the 20th century, the creek’s presence still impacted the 19th century residents who lived at White Haven. While the exact location of the cabins housing the enslaved African American people are unknown, the enslaved had to cross Little Prairie Creek each morning as they went to work. It is believed the creek was used for various other tasks, including collecting water for the livestock to drink and as a source of drinking water for the Dent, Grant, and enslaved family. Today, Little Prairie Creek stands as a flourishing riparian corridor that feeds into the larger Gravois Creek watershed, both of which provide an insight into the ever-evolving relationship with the landscape at White Haven.

National Park Service

The topography of White Haven has also changed drastically since the home was first constructed. Over the past 200 years, the property has been altered from its initial wooded state to a working plantation and then a residential estate throughout the 20th and into the 21st century. During the period that the Dent family and Ulysses S. Grant owned the property (1820-1885), many crops were grown across their 850 acres of land. In a letter to his father in 1858, Grant laid out his plans for what he wanted to grow on the 80 acres of land given to him by Colonel Dent.

“My intention is to raise about twenty acres of Irish potatoes, on new ground, five acres of sweet potatoes, about the same of early corn, five or six acres cabbage, beets, cucumber pickles & mellons and keep a wagon going to market every day.”

The evolution of the White Haven estate into a working farm was undoubtedly one of the biggest changes the landscape went through, but the 20th century brought around change of a different kind - urban sprawl extending outward from St. Louis. In 1830, a few years after the Dent family started using White Haven as a year-round home, the population of St. Louis was just under 5,000 people. By 1930, St. Louis was the 7th largest city in the United States, with over 800,000 residents within the city limits. Many different parties started moving out from the city center and bought land from the White Haven property, including August A. Busch of Anheuser-Busch brewing, who purchased a sizeable portion of the estate in 1903. By the 1980s, very little remained of the original 850 acres acquired by Colonel Dent. The farmland used by Colonel Dent and Grant had been mostly converted to residential housing or in the case of Anheuser-Busch’s portion of the property, an animal park.

When the National Park Service acquired the property in 1989, changes began to turn White Haven into an official national park unit, with walking paths constructed around the home and a visitor center opening in 2005. Each of these changes to the landscape over the years has impacted the relationship between the people and the land in different ways. By converting the landscape to farmland, the Dent and Grant families were undergoing a years-long process, as outlined in this passage from former Park Historian Pam Sanfillippo's research study, "Agriculture in antebellum St. Louis":

“Farmers also mended tools and prepared for spring planting during the winter months. Turning unimproved land into cultivated fields took several years, depending on what was currently growing on the land. Any trees had to be chopped or burned down.The remaining trunks and roots were usually worked around for several years, until they rotted enough for easier removal.”

The enslaved African-Americans at White Haven were greatly impacted as well, being forced to assist with the crop production that occurred before the Civil War but also using the natural landscape for their own benefit as well. Although the farmland no longer exists today, artifacts in the park’s museum still shed light on White Haven’s agricultural past. When looking at the history of a site like White Haven, it is important to take into consideration all aspects of the property, and that means going beyond man-made structures to the very land itself. Little Prairie Creek, as well as the landscape that surrounds it, are two excellent examples of how the residents of White Haven’s relationship with the landscape has changed over time, and how it will continue to evolve into the future. By respectfully observing the rules of the park, visitors can help ensure that the landscape of Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site is maintained for future generations.

Further Reading

Grant, Julia Dent. The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant. New York: Putnam, 1975.

Sanfillippo, Pam. "Agriculture in Antebellum St. Louis." 1999. Available at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site Research Files.

Simon, John Y. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 1: 1837-1861. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967.

Weekly, Mark. Cultural Landscape Assessment: Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site. 1993. Available at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site Research Files.