Last updated: November 29, 2023

Article

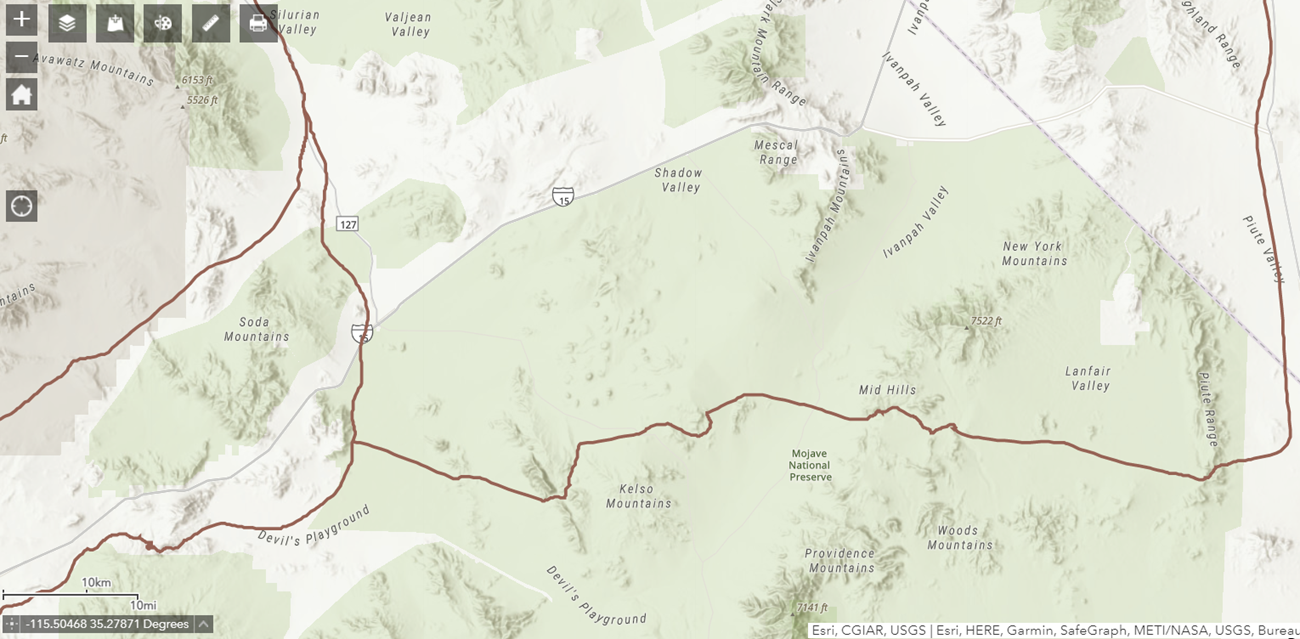

The Mojave Road & The Old Spanish Trail

NPS Image

Read more to learn about the history of this significant travel corridor.

Summary

The Mojave Road was built with congressional funding in 1857-60 as a transportation corridor linking California to the southwest and presently bisects what has since become the Mojave National Preserve (MOJA). The passage through the desert that later became the Mojave Road served for centuries as a vital trail system for Native Americans tribes of the southwest. The first documented European exploration of the Mojave Indian Trails came from the Francisco Garcés expedition in 1776.

The trail system became significant in American history when trapper Jedediah Smith passed through the region in 1826, followed by Antonio Armijo in 1837 and John C. Fremont in 1844. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War in 1848, brought the region of the Mojave Indian Trail under control of the United States. In 1853 the U.S. Topographical Engineering party of Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple followed the Indian trail system through MOJA as part of their Transcontinental Railroad survey. Whipple’s influential and widely circulated survey report resulted in the construction of the Mojave wagon road by Lt. Edward Fitzgerald Beale between 1857-60.

After the Civil War the Mojave Road was the main mail link between Southern California and Arizona. Conflict between travelers and Native Americans resulted in an increased military presence and the construction of small forts and redoubts along the road. The U.S. military used the road extensively to move men and supplies from Los Angeles to and from Fort Mohave on the Colorado River. Use of the road by miners, homesteaders, and ranchers continued in the 1870s, though cessation of Native American hostilities meant the Army no longer had reason to occupy the forts. After the completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1883 the road fell into disuse.

Portions of the road were used through the twentieth century by ranchers, farmers and the military but the majority of the historic road reverted to native vegetation. The complete road was rediscovered and carefully uncovered during the 1960s and 1970s. The road and its associated resources maintain a high degree of integrity clearly reflecting its important historical associations.

Early Use

Native Americans inhabited the Mojave Desert for several millennia.[1] In the area around Lake Mojave (an ancient Pleistocene lake bed that occupied the basin of present-day Soda and Silver Dry Lakes), archaeologists have collected artifacts dating to at least 5,000 B.C.[2] Geologists “conclude that early people were living around the lake 10,000 years ago.”[3] Thousands of years later, between 1,500 and 500 B.C., these modern tribes—ancestors of the Mojave Indians—began to settle in small villages near the Colorado River.[4]

Along the banks of the Colorado, the Mojave Indians developed agricultural practices suited to their arid environment. In late prehistoric times the tribes of the Mojave Desert established trade routes extending from the Colorado River to the California coast.[5] Reaching the Pacific coast required crossing the eastern, barren portion of the Mojave Desert, known for its paucity of water. Thus, the Mojave blazed trails between known water sources to ensure safe passage. Though the Mojave’s exact path may have varied “depending on the availability of water which changed with the seasons and rainfall,” one of the most-traveled trails led from the Mojave villages on the Colorado River to Piute Springs, Rock Springs, Marl Springs, and Soda Springs—comprising the present-day route of the Mojave Road as it exists within the Mojave National Preserve.[6]

After Euro-American contact the Mojave established trade with Spaniards in the coastal California missions to the west and extended their trade network to Native American tribes to the east in Arizona.[7] Mojave traders most frequently headed to Mission San Gabriel, located near present-day Los Angeles. There, the Mojave sought cuentas, “certain seashells highly prized by the Indians…a brisk trade was carried on in them between tribes of the interior and those of the coast where they were found.”[8] In exchange for shells, the Mojave traded “pottery, gourds, dried pumpkin, mesquite beans, and other food products. They also acted as middlemen, bringing blankets and other goods manufactured by the Hopis to trade with the coastal and mountain Indians far to the west of the Mojave Villages.”[9] Observant Anglo travelers noted that the Mojave had “certain blankets that they…weave of furs of rabbits and otters brought from the west and northwest, with the people of which parts they keep firm friendship.”[10]

The Mojave Indians played a crucial role as guides for early Spanish and Anglo-American explorers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Though the Mojave had contact with the party of Spanish explorer Juan de Oñate in 1604, Father Francisco Tomás Hermenegildo Garcés was likely the first Anglo to traverse portions of the Mojave Trail.[11] In 1775, Garcés, a priest affiliated with Mission San Xavier del Bac in Tucson, Arizona, traveled with the party of explorer Juan Bautista de Anza from Tucson to Yuma. Though Anza pushed on to his final destination near San Francisco, Garcés traveled up the Colorado River to the Mojave villages at present day Needles, California in early 1776, accompanied solely by Native Americans. His Mojave guides “lead him over a well-worn trading trail.”[12]

His secular objective involved determining the viability of a route leading from settlements in New Mexico to coastal missions in California. At the Mojave villages, Garcés sought the assistance of the tribe, explaining the “desires that I had to go to see the padres that were living near the sea; [the Mojave] agreed and offered soon to accompany me, saying that already they had informations [sic] of them and knew the way.”[13] Three guides agreed to accompany him to Mission San Gabriel, covering the distance in roughly twenty days. Along the way, they passed just south of Piute Springs and Soda Lake.[14] At several points along the way, the party met groups of Jamajab (Mojave Indians) and described their trading activities. One group was “coming from Santa Clara, after trading in shells”; another was “returning from San Gabriel from their commerce, and very content to have seen the padres, who had given them corn.”[15] Two months later, Garcés returned to the Mojave villages, again by way of the Mojave Trail.

Jedediah Smith

Fifty years later, in 1826, fur trapper Jedediah Smith roughly followed Garcés’ path through the Mojave, becoming only the second explorer to record the journey.[16] One of the era’s best-known fur trappers, Smith departed north-central Utah in August 1826 and headed southwest with eighteen men. In October, the group reached the Colorado River and the surrounding Mojave villages, where Smith “learned that the Mexican settlements on the California coast were not far and that the Indians knew the way there.”[17] With guides leading the way, Smith made the cross-desert trek, passing Piute Springs, Marl Springs, and Soda Lake while traversing the Mojave Road.[18] In doing so, he became the first Anglo-American to reach California by land. Smith’s southern passage across the route of the Mojave Road brought national attention to the Mojave Trail. While only lightly traveled over the following thirty years the strategic importance of this southern transportation link between California and the Mexican-American borderlands was established by Smith’s successful journey in 1826.

When Smith crossed the Mojave Desert he was deep inside Mexican territory without permission. His exploits in 1826 made him a hero in America but led to a serious confrontation with the Mexican Governor of California José María Echeandía. Border incursions like Smith’s so concerned Echeandía that he briefly imprisoned the trapper and ordered him out of Mexico after his release. Mexican officials like Echeandía worried about the destabalizing effect traders like Smith might have on the tenously controlled desert Northwest territories. Most Californíos in remote and sparsely populated regions like the Mojave, however, welcomed foreign commerce aiding the growth of U.S. trade inside Mexican territory despite the concerns of Mexican officials.[19]

Those Mexican officials familiar with the northern frontier regions also had reason to fear the effect of American trade on relations with the so called “Indios Bárbaros” who regularly attacked Mexicans throughout the Northwest territories checking Mexican expansion into their newly won frontier and undermining Mexican athority in the region.[20] Between 1821 when Mexico gained its independence and 1848 intertribal conflict and war between Mexicans and various regional tribes created the “most serious obstacle to progress and prosperity” for the Mexican North.[21] The area now encompassed by the Mojave National Preserve was on the fringes of a “War of a Thousand Deserts” that pitted Indians against Mexicans on the eve of the U.S.-Mexican war.[22]

Undaunted by Mexican authorities Smith returned to the Mojave Trail again in August 1827, but this time with deadly consequences. On the 18th, his party began crossing the Colorado, “horses swimming and provisions and gear loaded on a cane raft. With Smith and eight men in midstream, the Mojaves suddenly attacked. Ten men remaining on the shore fell victim to arrows and clubs, while the others fended off waterborne assaults.”[23] Smith and the other eight survivors retreated into the desert with few provisions and no knowledgeable guides to lead the way. They managed to find their way to the Mojave Trail and travel west to safety.[24] This encounter forshadowed a pattern of conflict and violence that characterized travel through the region for the following sixty years.[25]

The attack on Smith dramatically decreased Mexican and American use of the Mojave Indian Trail. Though the trail system was one of the most direct paths linking New Mexico, Arizona and California, stories of the Mojave’s hostility limited its use. Without the conflict, “[a] direct trail would very likely have been developed between the settlements on the upper Rio Grande in New Mexico and California by way of northern Arizona and the Mojave Indian Trail.”[26] Instead, explorers, traders, settlers and emmigrants often opted for the more northerly Old Spanish Trail, avoiding the Mojave Trail.[27]

Despite its reputation for violence, other traders chose to use the Mojave Trail after Smith. Richard Campbell likely utilized it in late fall of 1826 or early winter of 1827 on a trek from Taos, New Mexico to California.[28] In 1830, the Ewing Young party (including a young Kit Carson) “followed a route already twice traveled by Jedediah Smith and once by Richard Campbell—the Mojave Desert and River to Cajon Pass through the San Bernardino Mountains.”[29] William Wolfskill, George Yount, and Peter Skene Ogden also all passed on or very near the trail during their trapping expeditions.[30]

U.S. Military Explorers & Surveys

In the late 1830s, a new type of traveler began trekking across the region. U.S. military explorers, surveying and mapping the western territory’s resources and gauging the region’s suitability for settlement, traversed portions of the Southwest, including southern California. Beginning with Lewis and Clark’s 1804-06 expedition, the federal government began financially backing expeditions to penetrate the western reaches of the continent. While these journeys were as exploratory in nature as the eighteenth-century Garcés expedition, the Army professionalized the exploration of the West by establishing the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1838. Taking orders directly from the President and the Secretary of War, the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers began systematically surveying the West with the purpose of looking for practical applications that would assist expansion of settlers across the continent. The presence of representatives of the U.S. government in the Mexican southwest demonstrated the region’s growing strategic importance. The activities of the Corps took on new importance after the U.S-Mexican War of 1846-48 resulted in the aquisition of the southwest by the United States.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in January 1848, bringing the region of the Mojave Road into the United States and opening the area to systematic exploration.[31] After 1848, the Southwest assumed new importance in the development of the U.S., as “[w]hat had once been a forlorn gateway to imaginary cities of gold…became a well-tramped corridor to some very real cities of gold on the Pacific shore.”[32] The exploration and development of transportation corridors across the newly-acquired territories became a national concern, inspiring the most significant period of government-sponsored exploration since the Lewis and Clark expeditions.

The year 1853 proved to be the “climatic year” of the “Great Reconnaissance” of the newly consolidated American West.[33] Secretary of War Jefferson Davis ordered six parties of topographers, naturalists, artists, and support staff into the West in search of “the most practicable and economical route for a railroad to the Pacific Ocean.”[34] The Thirty-Second Congress authorized generous funding for the surveys, which “resulted in the first attempt of the government to conduct a comprehensive and systematic examination of the vast region lying between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean.”[35] More than simple topographic exercises, 1853 government surveys were among the most significant, systematic, scientific studies of nature, culture, and geography in United States history. In the opinion of eminent historian William Goetzmann, they were also among the most significant in the history of the modern world.

Not since Napoleon had taken his company of savants into Egypt had the world seen such an assemblage of scientists and technicians marshaled under one banner. And like Napoleon’s own learned corps, these scientists, too, were an implement of conquest, with the enemy in this case being the unknown reaches of the western continent. The immense quantity of data collected by these government scientists constituted a plateau from which it was possible at last to view the intricacies of western geography.[36]

In the words of Mojave historian Dennis Casebier, the survey parties were “the astronauts of their day.”[37]

Whipple's Expedition

One of the 1853 railroad survey parties was assigned an area that stretched from the 35th parallel south through the lower Southwest and the Mojave Desert. The Army commissioned Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple to survey a possible route between Fort Smith, Arkansas and Los Angeles, California. [38] One of Whipple’s primary goals was to determine whether the Mojave River flowed into the Colorado. Smith and other trappers knew that it didn’t, but the government wasn’t convinced.[39] Whipple’s expedition followed the Mojave Indian Trail system, producing a rich record of the resource at that moment in history. Between Fort Mohave on the Colorado River and Camp Cady south of the current boundaries of the MOJA, Whipple surveyed and named important watering holes and landmarks along the Mojave Trial.[40] Whipple’s accounts specifically described the primary trail and its associated resources in great detail, particularly Pah-Ute Creek, Rock Springs, Marl Springs, and Soda Lake.[41] His small wagon, loaded with the latest scientific instruments of his day, was the first to travel the trail. The Whipple expedition produced important maps, geographic and botanical descriptions and tactical information for future railroad builders, traders, and prospectors.[42]

The expedition also carefully described the Mojave Indians. By most accounts, Whipple’s relationship with the Mojave was one of respect and interest; he made agreements with tribal leaders to expand the trade route “for the mutual benefit of both peoples.”[43] Conflicting understandings of Whipple’s promises to the Mojave shaped later interactions with the Beale expedition and other travelers who came in increasing numbers into Mojave territory.

Whipple’s expedition artist, German-born Heinrich Baldwin Möllhausen, captured the region in “majestic panoramas of the desert and portraits of brightly attired native peoples.” These images traveled the globe as the “most striking achievement” of the 1853 surveys and were instrumental in shaping national opinions about America’s southwestern deserts and the Indians of the region.[44] In keeping with the era’s artistic traditions, Möllhausen drew the Mojave Desert and its people through the era’s “Romantic horizon,” blending rigorous scientific inquiry with idealized depictions of what mid nineteenth-century Americans expected deserts to look like. The government published the results of the surveys in twelve “lavishly illustrated volumes” made widely available as a “virtual encyclopedia of the West.”[45] Möllhausen published his own account of his travels across the Mojave Road; they circulated throughout Europe ensuring that the remote Mojave Desert was internationally known as a route to California through an exotic landscape peopled by a significant tribe of previously little-known Indians.[46]

Edward Beale

Though Whipple’s expedition is most clearly associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our national history, it was Edward Fitzgerald Beale who was tasked in 1857 with the actual construction of a wagon road following the route of the railroad surveys, including the section that comprises the historic Mojave Road through the Mojave National Preserve.[47]

Beale was one of the most famous explorers of the 1850s, having fought with Kit Carson in California, befriended John C. Fremont, and traversed the continent from coast to coast more than a half dozen times.[48] His trip across the Mojave with a caravan of camels solidified his place in the pantheon of American pathfinders. [49] A “former Navy officer, Mexican War hero…and superintendent of Indian affairs for the state of California,” Beale’s reputation ensured his Mojave expedition received national coverage.[50] In 1857, Secretary of War John B. Floyd appointed Beale superintendent of a wagon road survey of the 35th parallel from Fort Defiance, New Mexico to the Colorado River. When Beale reached the Colorado with his troops of surveyors and camels, he found a “regularly traveled road to Los Angeles” with stops at the well-established strategic springs along the route; thus he decided to push on to land he owned in western California.[51] Beale traveled the “Mojave Road” presumably following Whipple’s route.[52] His otherwise very thorough report to the Secretary of War (1857) is missing the Mojave desert portion of his trip. The report lacks information on this final push because the U.S. government did not pay for the road building past the Colorado. It is certain, however, that Beale served as superintendent for the survey and improvement of a wagon road over the 35th parallel from Fort Defiance, New Mexico to the Mojave villages on the Colorado River between 1857-60. Grading and improvement of the Mojave Trail into an official government wagon road through the MOJA occurred under Beale’s direction during this time. The improved road Beale constructed became known as “Beale’s Wagon Road,” with “Mojave Road” or “Government Road” used interchangeably in the following decades.

Increased Traffic and Tensions

Like other critical transportation routes through the still sparsely-settled Southwest, the Mojave Road became a focal point for military efforts to control contact between Native American residents and new travelers.[53] Though not unique in the history of western military defense of newly explored territories, the events that unfolded between 1857 and 1883 along the section of the Mojave Road that now traverses the MOJA drew national attention and provide an outstanding example of patterns of contact and conflict on transit corridors during a critical period in the nation’s history.

Immediately after Beale’s notable survey, the Mojave Road became a vital transportation route for mail and material between Arizona and California. Arizona experienced a mining boom at this time and the Mojave Road became the primary path for transportation and communication between Arizona mining centers and the mineral markets of California. Following the Mountain Meadows Massacre of September 1857 emigrant travel on the road increased dramatically.[54] Following the Mormon attack on a wagon train of western emigrants, the U.S. military initiated a punitive campaign against the Latter-Day Saints, sparking fears of a brewing “Mormon War” and pushing travelers south from the Spanish and Mormon Trails to the Mojave Road. Thus, a convergence of factors resulted in the Mojave Road becoming the “prime link between Southern California and the East” between 1858 and 1868.[55] Increased traffic on the Road caused new tensions between travelers and the Mojave Indians; confrontations between these two parties received wide attention in the regional press, resulting in scrutiny from Washington, D.C.[56]

On August 30, 1858, a wagon train of emigrants fought a pitched battle with the Mojave on the banks of the Colorado. After days of tension over emigrant clearing of precious cottonwood tress and Indian theft of cattle, a fight erupted, resulting in widespread injury and the death of two settlers and at least 17 Indians.[57] The event was indicative of the persistent cultural misunderstandings that defined violence on the Mojave Road. Though the Indians suffered greater loss of life than the white settlers, the press described the event as a “massacre,” with southern California newspapers such as the San Bernardino Times and the Los Angeles Star offering to readers extensive, increasingly lurid stories of unprovoked attack on travelers by “savage” Indians.[58] Such incendiary reporting of tensions contributed to growing popular support for military action against the Mojave.

The growing economic importance of the Mojave Road, fear of an Indian uprising, and public outcry over the attack on the emigrants at the Colorado inspired General N.S. Clarke, Commander of the Military Department of California, to issue orders to Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman of the Sixth Infantry to locate a post within striking distance of the Indians suspected of attacking travelers on the Mojave Road.[59] Beale had strongly encouraged the location of a fort at the strategic river crossing just months before the attack:

“I regard the establishment of a military post on the Colorado River as an indispensable necessity for the emigrant over this road; for, although the Indians, living in the rich meadow lands, are agricultural, and consequently peaceable, they are very numerous, so much that we counted 800 men around our camp.”

These numbers led Beale to conclude that conflict was inevitable.

“The temptations of scattered emigrant parties with their families, and the confusion of inexperienced teamsters, rafting so wide and rapid a river with their wagons and families, would offer too strong a temptation for the Indians to withstand.”[60]

In April 1859, Hoffman arrived at “Beale’s Crossing” at the Colorado River with 700 troops to establish a military post at Camp Colorado (later named Fort Mohave). Hoffman’s overwhelming show of military force enabled him to secure the site for the fort and extract a formal surrender from the Mojave, who promised safe passage for travelers and to allow military use of the Mojave Road in the future. [61] In subsequent years, the military established a series of outposts at Piute Springs, Rock Springs, Marl Springs, Soda Springs and Camp Cady. Supplying a geographically-isolated outpost like Fort Mohave created a major challenge for the frontier army. The military had only two options: bring supplies across the Rio Grande and up the Colorado River or pack them over the Mojave Road across some of the driest expanses of the eastern Mojave Desert. In 1859, after conducting cost efficiency tests, Captain Winfield Scott Hancock found the cost of land-based transportation significantly lower than river transport.[62] Thus, between 1859 and 1883, though prospectors and other travelers used it, the Mojave Road served mainly to facilitate west-to-east supply of Fort Mohave as well as military escorted mail transport. This consistent usage meant that “[t]he Mojave Road became a line on maps…labeled ‘wagon road.’ The Mojave Road would serve in that role for the next twenty years as one of the main life lines to developments that were commenced in the wilderness of the eastern Mojave Desert in California and northwestern Arizona.”[63]

Increased traffic on the road in 1859 and 1860 led to further clashes with the Indian tribes of the region. Once again, regional newspapers reported the incidents extensively and lobbied for greater military control of the road and protection of its critical water resources. In January 1860, for example, the Los Angeles Star reported that a group of “Pah-Ute” Indians killed Robert Wilburn during a cattle raid.[64] Two months later, more reports of Indian attacks followed. Indians killed Thomas S. Williams and Jehu Jackman after offering to show them water and grazing lands. Newspapers called for a military post on the Mojave Road between Los Angeles and Fort Mohave, as did a petition drafted and circulated in Los Angeles for submission to the governor.

In response to the three deaths, General Clarke ordered Major James Henry Carleton to lead two cavalry companies in a campaign against the Indians in April 1860, not “to attempt to locate the guilty Indians, but simply to chastise any Indians he might discover in the vicinity [of the murders].”[65] His two-month search-and-patrol operation of the area between Los Angeles and Fort Mohave necessitated construction of a base camp, which Carleton named Camp Cady and completed in May 1860. After Carleton issued terms of peace in early July 1860, he and his troops abandoned Camp Cady. However, before their return to Fort Tejon, California, they also constructed unmanned redoubts at Soda Springs, Marl Springs, and Bitter Springs, locating each redoubt near a water source and building them large enough to accommodate a large company with animals and wagons.[66]

1860s & Postal Service

Shortly after the completion of this series of outposts, the Civil War drained the western frontier of nearly all soldiers. On May 28, 1861, the U.S. Army abandoned Fort Mohave as troops moved out to fight the Civil War in the East.[67] However, concerns that supporters of the Confederacy were moving from California to Texas resulted in the deployment of two companies of troops to re-open the fort in May 1863.[68] Not long after the reoccupation of Fort Mohave, the 2nd California Calvary moved to Camp Cady under orders to protect travelers and clear the road of Indians. Over the course of the next decade, the Army garrisoned Camp Cady with soldiers intermittently. As Prescott, the capital of the newly-established territory of Arizona, became crowded with miners seeking fortune in nearby areas and with the businessmen looking to provide them merchandise and services, the Mojave Road became a vital link on which goods traveled to the city from the port of San Pedro and the city of Los Angeles. By early 1864, “there was a constant flow of military and civilian traffic rolling over the Mojave Road.”[69]

Between 1864 and 1867, the Mojave Road served as the primary mail route between California and Prescott. In 1864, Arizona Governor John Noble Goodwin asked the Postmaster General to open a line of mail service to Arizona as a part of the existing mail route from California to New Mexico. At the time, the U.S. Army and a private express delivered mail to these outlying territories on an irregular basis from Drum Barracks (near Wilmington, California) to Fort Mohave. Officials did not consider the Mojave Road at first for a mail route because the La Paz Road (to the south) appeared more suitable.[70] However, due to political maneuvering and a stipulation in the mail contract that the mail from San Bernardino to Prescott had to go by way of Hardyville, Arizona, the Mojave Road became the official mail route. On March 1, 1865, Sanford J. Poston received the contract to carry mail once a week in each direction. However, the military continued to play an important role in the protection of the mail delivery route because of continued tensions with Native Americans.[71]

Conflict between mail carriers and the Paiute and Hualapai tribes caused considerable delays in the delivery of the mail, much to the discontent of the Arizonans who pressed for still more military presence. Thus, in June 1866, the Army re-garrisoned Camp Cady to help secure the road as a mail route and provide protection for travelers on the road.[72] On July 29, a fight broke out between a band of roughly three dozen Paiutes and a half dozen soldiers stationed at Camp Cady; the American commander assumed the Indians were hostile and there to attack the camp, so he struck preemptively. His actions resulted in the deaths of three soldiers and the wounding of three others while “[a]t the same time [raising] the public cry in the settlements for troops to be brought in to protect the road.”[73] By September 1866, mail riders stopped at Camp Cady requesting safe escort against Indian attacks to Fort Mohave, and the need for such frequent escorts caused the commander to request guidance on the matter. Army officials replied that escorts should be provided and a post should be established at Rock Springs with other smaller outposts established at Soda Springs, Marl Springs and Pah-Ute Creek in order to limit the distance each set of military escorts had to travel and to provide stops for the mail riders.[74] By March 1867, the mail traveled twice a week from and to Los Angeles in light wagons escorted by military troops; Concord stages soon followed.[75] Regular attacks on mail riders, nearby miners, and livestock continued into 1867; the Army continued to provide mail escorts but did little else.

The high number of attacks spelled the end of mail traffic along the Mojave Road. Arizona authorities had inspected the two routes in early 1867 and found that the La Paz Road to the south better suited for reliable mail transport. In the winter of 1867-68, massive flooding washed out sections of the Mojave Road. The road was reopened but never saw the same levels of use again. In May 1868, the Army decomissioned the redoubts at Rock Springs, Marl Springs, Soda Springs and dispersed the troops to other bases in California.[76]

Decreased Use & the Road Today

Although military operations continued along the Mojave Road in the 1870s, they were far less notable or frequent. Steamboat transportation up and down the Colorado River soon became the primary method of moving supplies and troops. As traffic subsided and Indian resistance faded, the Army abandoned Camp Cady in 1871. However, civilian traffic on the Mojave remained steady throughout the 1870s thanks to scores of prospectors and miners seeking fortunes in nearby towns such as Ivanpah, California. The Mojave Road’s other primary travelers were herds of sheep and cattle being driven to newly-opened ranges in Arizona and New Mexico.[77]

The 1883 completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad line connecting Barstow and Needles fifteen miles south of the Mojave Road ended the road’s regular use and period of national significance. New roads and wagon traffic followed the rail lines enabling travelers to “avoid the high Providence Mountains” of the Mojave Road and more efficiently traverse the desert.[78] Portions of the road saw use throughout the twentieth century by ranchers, farmers and the military but the majority of the historic road reverted to native vegetation. The complete road was surveyed and carefully uncovered during the 1970s by researcher Dennis Casebier.[79] Despite changing usage over time the road maintains a high degree of integrity and clearly reflects its important historical associations. The reopening of the road through the area now encompassed by the Mojave National Preserve added significant traffic from outdoor recreationalists and four-wheel drive enthusiasts to the historic road enabling this historic resource to remain free of encroaching vegetation while preventing erosion and deterioration of the resource through consistent use.

In addition to its historic role relative to exploration and transportation, the Mojave Road also holds significance as a site associated with reknowned historical figures. Primarily, the Mojave Road offers a strong representation of Edward F. Beale’s and Amiel W. Whipple’s historical contribution to the American Southwest. While the National Register lists a number of sites associated with Beale and Whipple, few are directly related to this aspect of the mens’ historical activities. Concerning Beale, one can find the Decatur House in Washington, D.C., Ash Hill mansion in Prince George County, Virginia, and Camp Beale’s Springs near Kingman, Arizona listed on the National Register. Virginia’s Fort Myer Historical Site is, likewise, directly related to the eastern activities of Whipple.

The historical significance of Decatur House and Ash Hill is drawn from the houses’ association with notable historical figures other than Beale, and has no association with his activities in the American Southwest. Prior to Beale’s purchase of Decatur House, famed naval officer Stephen Decatur owned and occupied the domicile.[80] During Beale’s tenure at Ash Hill from 1875 to 1895, notables such as as Ulysses S. Grant, Grover Cleveland, and William “Buffalo Bill” Cody frequented the residence.[81]

Whipple founded Fort Whipple as a U.S. Army post across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. in 1863 as the Civil War raged throughout the East. The United States military redesignated the structure Fort Myer in 1881, in honor of Brigadier General Albert J. Myer. Fort Myer eventually gained historical significance as the site of the first fixed-wing military aircraft flight. It also held the distinction of being the site of the first fatal airplane accident in the United States, which occurred in 1908.[82]

Only Camp Beale’s Springs harbors some relationship to Beale’s activities regarding the Mojave Road and the exploration and the settlement of the Southwest. Beginning in 1859, Beale’s surveying and road construction parties used the area as a watering stop. Soon thereafter, it became a stopover point on the Prescott Toll Road which connected the Prescott, Arizona with the Colorado River town of Hardyville. Beale’s Springs’ primary historical significance accrued during and after the Hualapai War of 1867-1870 as a military post, site of combat, and temporary reservation for the Hualapai.[83]

Notes

[1] Though the culture of the Mojave Indians is a vital part of our national and regional history, its extended treatment is not pertinent to this nomination. The archeological record of Mojave life and culture along the Mojave Road is extensive and well documented. Currently the best published sources on the Mojave Indians from the time of contact are the collected works of Lorraine M. Sherer. Sherer and long-time research partner, Mojave elder Frances Stillman, produced a series of significant articles on Mojave Indian history and culture, and posthumously, a valuable collection in book form, Lorraine M. Sherer, Bitterness Road: The Mojave, 1604 to 1860 (Menlo Park: Ballena Press, 1994). The Sherer Collection (UCLA Special Collections, Collection 1225) holds the author’s extensive research files, oral interviews, and manuscripts indicating collaborations with Mojave tribal members. Also, note that there is discrepancy within historical and scholarly documents about the spelling of “Mojave.” In this nomination, the spelling conventions used by historians and the Mojave Indian Tribe will be followed, utilizing Mojave (with a j) as opposed to Mohave (with an h), with the exception of the name Fort Mohave, the accepted historic spelling for that site.

[2] Chester King and Dennis G. Casebier, with Matthew C. Hall and Carol Rector, Background to Prehistoric and Historic Resources of the East Mojave Desert Region (Riverside, Calif.: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, California Desert Planning Program, 1976), 23.

[3] Thomas H. Ore and Claude N. Warren, “Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene Geomorphic History of Lake Mojave, California,” Geological Society of America Bulletin 82, no. 9 (1971): 2553-2562.

[4] King and Casebier, Background to Prehistoric and Historic Resources of the East Mojave Desert Region, 27.

[5] Alfred L. Kroeber, Handbook of the Indians of California (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, 1925; Berkeley, California: California Book Company, 1967), 735.

[6] Dennis G. Casebier, The Mojave Road, Tales of the Mojave Road, No. 5 (Norco, Calif.: Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing Company, 1975), 15. See also Dennis G. Casebier, Reopening the Mojave Road: A Personal Narrative (Norco, Calif.: Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing Company, 1983). Dennis G. Casebier, Mojave Road Guide: An Adventure through Time (Goffs, Calif.: Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing Company, 1999). For more on Casebier’s remarkable volume of publications and matchless Mojave Road archival collection, see bibliography and note on sources.

[7] Mojave trading in Arizona is mentioned in Royal B. Stratton, Captivity of the Oatman Girls: Being an Interesting Narrative of Life among the Apache and Mojave Indians (New York: Published for the Author by Carlton & Porter, 1858), 150. For a more contemporary reconsideration with considerable input from Mojave tribal sources, see Margot Mifflin, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman (Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 2009).

[8] Francisco Garcés, On the Trail of a Spanish Pioneer: The Diary and Itinerary of Francisco Garcés (Missionary Priest) in His Travels Through Sonora, Arizona, and California, 1775-1776, Translated from an Official Contemporaneous Copy of the Original Spanish Manuscript, and Edited with Copious Critical Notes in Two Volumes, ed. and trans. Elliott Coues (New York: Frances P. Harper, 1900), 1:236-237.

[9] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 13.

[10] Garcés, On the Trail of a Spanish Pioneer, 1:230-231.

[11] The Mojave encounters with the Oñate expedition are described in Herbert E. Bolton, ed., Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1542-1706 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), 268-71. For analysis of the web of trails through the region see, Elizabeth Von Till Warren and Ralph J. Roske, Cultural Resources of the California Desert, 1776-1980: Historic Trails and Wagon Roads (BLM Cultural Resources Publications, 1981), 21-22.

[12] David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 253.

[13] Garcés, On the Trail of a Spanish Pioneer, 1:232-233.

[14] Ibid, 1:235-239.

[15] Ibid, 1:236-7, 243.

[16] LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Vol 8. (Norman: Arthur H. Clark, revised editions, 2003); Dale Morgan, Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1953). Excerpts from Smith’s experiences in the Mojave National Preserve area may be viewed at http://www.nps.gov/archive/moja/mojahtjs.htm. For context on Smith and lone fur trappers in the exploration of the West see, Clyde A. Milner, “National Initiatives,” in The Oxford History of the American West, ed. Clyde A. Milner, Carol A. O’Connor, Martha A. Sandweiss (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 155-60. For detailed source material on trappers and the Mojave, see Sherer, Bitterness Road, 8 (note 1). Warren, 21.

[17] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 23.

[18] Jedediah Strong Smith, The Southwest Expedition of Jedediah S. Smith: His Personal Account of the Journey to California, 1826-1827, ed. George R. Brooks (Glendale, Calif.: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1977), 86-89. See also http://www.nps.gov/archive/moja/mojahtjs.htm.

[19] Hubert Howe Bancroft, California Pastoral, 1769-1848. San Francisco: History Co., 1888. Robert Glass Cleland, This Reckless Breed of Men: The Trappers and the Fur Traders of the Southwest (New York: Knopf, 1950). Leonard Pitt, The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). For Smith and Echeandía see, David J. Weber, Foreigners in Their Native Land: Historical Roots of the Mexican Americans (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972), 56-57 and Maria Raquel Casas, Married to a Daughter of the Land (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2007), 112-13.

[20] David J. Weber, The Mexican Frontier, 1821-1846: The American Southwest Under Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982), 92-95. Weber specifically addresses the Mojave among other tribes at war with Mexico leading up to the U.S.-Mexican War.

[21] As quoted in Weber, The Mexican Frontier, 93. Weber cites Moises Gonzalez Navarro, “Instituciones indigenas en Mexico independiente,” in Metodos y resultados de las politica indigenista en Mexico (Mexico, 1954), 147-49 as the source for information on conflicts that may include the current boundaries of the Mojave National Preserve. See also, Sherburne F. Cook, The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976) and A.L. and C.B Kroeber, A Mohave War Reminiscence, 1854-1880 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), for theories of Mojave warfare and conflict. Kroeber argued that the Mojave “had been subject to some direct and some indirect Spanish-Mexican influences” but leaves the extent of those influences and their impact on the history of the region unexamined. Quote is from page 5.

[22] Brian DeLay, War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).

[23] Robert M. Utley, A Life Wild and Perilous: Mountain Men and the Path to the Pacific (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1997), 94.

[24] Smith, The Southwest Expedition of Jedediah S. Smith, 86.

[25] For analysis of conflicting accounts, theories of early conflict and source material on these encounters see, Sherer, Bitterness Road, 20-25 (notes 13-24). The notes provide insights from Sherer and Stillman and comments from editors Sylvia Vane and Lowell Bean on the Stillman’s interpretations. For Smith’s remarkable travels in context, see Robert V. Hine and John Mack Faragher, The American West: A New Interpretive History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 151-52. For conflict between Mexicans, Indians and Americans leading toward the U.S.-Mexican War see, Brian DeLay, War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).

[26] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 26.

[27] Exact routes are difficult to determine and the source of long debate. Some travelers who wrote of the Old Spanish Trail may have been on the Mojave Road and vise versa. See Harold Frederick Gilman, “The Origin and Persistence of a Transit Region: Eastern Mojave Desert of California” (Ph.D. diss., University of California Riverside, 1977), 100-104. This work contains clear, concise maps that attempt to show divergence and convergence of Mojave transit routes during this period. Warren and Roske, Cultural Resources of the California Desert also maps the various routes.

[28] Utley, A Life Wild and Perilous, 109.

[29] Ibid, 111.

[30] The first two are noted in King and Casebier, Background to Prehistoric and Historic Resources of the East Mojave Desert Region, page 285 and in Casebier’s The Mojave Road, page 32. Odgen’s encounter with the Mojave is recounted in Casebier’s The Mojave Road, page 28.

[31] In his 1977 Ph.D. dissertation, geographer Harold Frederick Gilman makes a convincing argument for using the concept of a “transit region” to understand the Mojave Desert’s history. Gilman systematically analyzes all the major trends in Mojave Desert history from prehistory to the 1970s, concluding that the constant movement of people, goods, and information from either side of the desert resulted in a “cultural landscape which is supported by serving the transit system.” Within that larger “transit region,” the Mojave Road functioned as the most significant transit corridor during its period of significance.

[32] D. W. Meinig, Southwest: Three Peoples in Geographical Change, 1600-1970 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 17. Meinig’s work is the best overview of the region’s cultural geography. Keith Heyer Meldahl, Hard Road West: History and Geology Along the Gold Rush Trail (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), provides an excellent model for understanding how geography influenced overland travel during the 19th century.

[33] William H. Goetzmann and William N. Goetzmann, The West of the Imagination (New York: W.W. Norton, 1986), 107.

[34] William H. Goetzmann, Exploration and Empire: The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the American West (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966), 281. Goetzmann’s classic is still the best source on the surveys of the West; it is excellent and detailed. See also Clifford J. Walker, Back Door to California: The Story of the Mojave River Trail, ed. Patricia Jernigan Keeling (Barstow, Calif.: Mojave River Valley Museum Association, 1986), 203; Eugene Tidball, Soldier-Artist of the Great Reconnaissance: John C. Tidball and the 35th Railroad Survey (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2004); David Howard Bain, Empire Express: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad (New York: Viking, 1999), 49-51. Bain’s work contains figures on the immense expense and diversity of specialists deployed.

[35] W. Turrentine Jackson, Wagon Roads West: A Study of Federal Road Surveys and Construction in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1846-1869 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952), 242-243.

[36] William H. Goetzmann, Army Exploration in the American West, 1803-1863 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), 305.

[37] As quoted in David Darlington, The Mojave: A Portrait of the Definitive American Desert (New York: Henry Holt/Owl Books, 1996), 72. For deeper context, see Michael Smith, Pacific Visions: California Scientists and the Environment, 1850-1915 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

[38] There is an extensive literature on the Whipple expedition. The most useful sources for establishing the historical significance of Mojave Road include: Amiel Weeks Whipple, A Pathfinder in the Southwest: The Itinerary of Lieutenant A. W. Whipple During His Explorations for a Railway Route From Fort Smith to Los Angeles in the Years 1853 & 1854, ed. Grant Foreman (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1941); Mary McDougall Gordon, ed., Through Indian Country to California: John P. Sherburne’s Diary of the Whipple Expedition, 1853-1854 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1988); Gilman, “The Origin and Persistence of a Transit Region,” 108. For broader significance and context, see Donald Worster, A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 126-35.

[39] See Casebier, The Mojave Road, 50-56.

[40] Walker, Back Door to California, 203.

[41] Whipple, A Pathfinder in the Southwest, 248-255; Gordon, ed., Through Indian Country to California, 194-202; Casebier, The Mojave Road, 54.

[42] Carl Briggs and Clyde Francis Trudell, Quarterdeck & Saddlehorn: The Story of Edward F. Beale, 1822-1893 (Glendale, Calif.: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1983), 203. Claude N. Warren, Martha Knack and Elizabeth Von Till Warren. A Cultural Resource Overview for the Amargosa—Mojave Basin Planning Units (BLM Cultural Resources Publications, 1980), 206.

[43] Quoted in Sherer, Bitterness Road, 65; see also Whipple, Reports, 242.

[44] Worster, River Running West, 131.

[45] Quote is from Milner, “National Initiatives,” 161. A. W. Whipple, Explorations For A Railway Route Near The Thirty-Fifth Parallel of North Latitude: Reports of explorations and surveys, to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, Vol. 3, Part 1 (United States. Army. Washington:A. O. P. Nicholson, printer [etc.], 1855-60). Pages 120-124 of Part 1 cover Whipple’s route through the nominated portion of the road. Key features of the historic route are also mentioned in Vol. 3, Parts 2-6 & Appendices. For the significance of railroad surveys, the Whipple expedition, and the Mojave Road, see also James P. Ronda, “Passion and Imagination in the Exploration of the American West,” in The Blackwell Companion to the American West, ed. William Deverell (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 68-69; and William H. Goetzmann, When the Eagle Screamed: The Romantic Horizon in American Expansionism, 1800-1860 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000).

[46] Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen, Diary of a Journey from the Mississippi to the Coasts of the Pacific with the United States Government Expedition, 2 vols. (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts, 1858).

[47] Walker, Back Door to California, 204. For an account of the sectional politics involved in railroad construction and the reasons why a wagon route from California to the Mississippi River was used as stop-gap measure, see Jackson, Wagon Roads West, 244-245 and Gerald Thompson, Edward F. Beale and the American West, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983), 104.

[48] Jackson, Wagon Roads West, 245.

[49] Lewis B. Lesley, ed. Uncle Sam’s Camels (New York: Oxford University Press, 1929); Odie B. Faulk, The U.S. Camel Corps: An Army Experiment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976).

[50] Darlington, The Mojave, 72-73.

[51] Quoted from Beale’s diary in Stephen Bonsal, Edward F. Beale: A Pioneer in the Path of Empire, 1822-1903 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 214.

[52] Lewis Lesley notes in his introduction to Beale’s journal that Beale provided only brief mention of the route through the present-day Mojave National Preserve on his way west to Tejon Ranch. Likewise, Beale makes no mention of his journey back east across the Mojave Road until he reached the Colorado again and found the steamboat General Jesup, the first to navigate the Colorado, waiting to carry him across, Uncle Sam’s Camels, 261. See also Faulk, The U.S. Camel Corps, 115.

[53] For context on wagon roads see, W. Turrentine Jackson, Wagon Roads West: A Study of Federal Road Surveys and Construction in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1846-1869 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952).

[54] Will Bagley, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002).

[55] Gilman, “The Origin and Persistence of a Transit Region,” 111-15.

[56] Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of the Pacific States, vol. 17, Arizona and New Mexico, (San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Co., 1889), 505. One of the best sources on the Mojave Road is WPA researcher Josephine R. Rumble’s History -- Old Government Road across the Mojave Desert to the Colorado River, Including the Pre-Historic, Works Progress Administration project no. 3428 (San Bernardino, Calif.: San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors, 1937). This indispensable reference includes descriptions of points of interest along the Mojave Road, excepts from letters and diaries of individuals that traveled along the road, a catalog of Indian petroglyphs in Grapevine Canyon in the Newberry Mountains, photographs of locations along the Mojave Road, and various newspaper articles.

[57] Sherer’s careful piecing together of sources remains the best source on this conflict. See Bitterness Road, 79-86.

[58] For one such inflammatory account of the emigrant-Mojave “massacre,” see Los Angeles Star, November 13, 1858. Additionally, both Rumble and Casebier summarize the press accounts of growing tensions and the public outcry that fueled military expansion into the region. Letters to the San Francisco Bulletin urging military intervention on the Mojave Road reflect public sentiment. Several such letters are reprinted in Dennis G. Casebier, The Mojave Road in Newspapers, Tales of the Mojave Road, No. 6 (Norco, Calif.: Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing Company, 1976), 7-9.

[59] Sherer, Bitterness Road, 87.

[60] E.F. Beale to James L. Orr, Speaker of the House of Representatives, April 26, 1858. Reprinted in Lesley, Uncle Sam’s Camels, 140-143.

[61] Sherer, Bitterness Road, 95-100; Dennis G. Casebier, Carleton’s Pah-Ute Campaign, Tales of the Mojave Road, No. 1 (Norco, Calif., The Kings Press, 1972), 3; Charles Ernest Hutchinson, “Development and Use of Transportation Routes in the San Bernardino Valley Region, 1769-1900” (M.A. thesis, University of Southern California, 1933), 76.

[62] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 103.

[63] Ibid, 105.

[64] A long series of stories on violence between travelers, soldiers, and Indians appeared in the Los Angeles Star between January and March, 1860. Several of these stories are reprinted in Casebier, Carleton’s Pah-Ute Campaign, 4-7; the Los Angeles petition is on page 9. Information regarding press coverage of locations and events along the Mojave Road can be found in Casebier, The Mojave Road in Newspapers and Rumble, History of the Old Government Road.

[65] Casebier, Carleton’s Pah-Ute Campaign, 12. Carleton’s crew killed two Indians; no further violence ensued.

[66] Ibid, 16, 48. For primary source confirmation of the establishment of Camp Cady and the redoubts, see Deseret News, Salt Lake City, Utah, July 9, 1860.

[67] Special Order No. 68, April 29, 1861, U.S. War Department Records, Series I, Volume 50, Part 1, 473-474.

[68] Hutchinson, “Development and Use of Transportation Routes,” 76.

[69] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 138.

[70] The La Paz Road (also known as Bradshaw Road) “left the San Bernardino valley by way of San Gorgonio Pass, reached eastward across the Colorado Desert, and struck the Colorado River near the town of La Paz. From there it traveled on to Prescott by way of Wickenburg.” See Dennis G. Casebier, Camp Rock Spring, California, Tales of the Mojave Road, No. 3 (Norco, Calif., Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing Company, 1973), 1.

[71] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 141-145.

[72] Ibid, 144.

[73] Ibid, 145.

[74] The order to establish Rock Springs can be found at Department of California, Special Orders No. 194, October 10, 1866 (National Archives, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Department of California Order Books, Vol. 187). Reprinted in Casebier, Camp Rock Spring, 3, 5. See also Casebier, The Mojave Road, 149.

[75] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 146.

[76] Casebier, Camp Rock Spring, 84.

[77] Casebier, The Mojave Road, 161.

[78] Ibid, 15, 161; Casebier, Camp Rock Spring, 85.

[79] Casebier details his work to research the road’s history while uncovering the road and restoring the roadway in his Reopening The Mojave Road: A Personal Narrative (Norco, CA: Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing, 1983).

[80] “Decatur House on Lafayette Square: A Brief History of Decatur House,” http://www.decaturhouse.org/history_decatur-house.html

[81] “National Register Listings in Maryland,” http://www.mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=434&COUNTY=Prince%20Georges&FROM=NRCountyList.aspx?COUNTY=Prince%20Georg

[82] “Fort Myer Historic District,” http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/aviation/ftm.htm

[83] Dan W. Messersmith. “Camp Beale’s Springs,” Mohave Museum of History and Arts http://www.mohavemuseum.org/beale.htm; See also: Dennis Casebier, Camp Beale's Springs and the Hualpai Indians (Norco, CA: Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing, 1980).