Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

The Melissa Pierce Project: Assessing the Cultural Landscape of Joppa, Texas and the Trinity River

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

National Park Service

Kathryn Holliday: Hi, good morning/afternoon. I have to say, as someone who grew up in New Orleans, I find it a little bit painful to be doing this on Mardi Gras. So, happy Mardi Gras. I considered bringing things to throw at this point in the day, but then I thought that I might accidentally hit someone. And that wouldn't be good, but happy Mardi Gras. And I should say, I am an Associate Professor of Architecture in the College of Architecture, Planning, and Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Arlington where I teach history to architecture and to landscape architecture students.

What I'll be presenting today is a case study of a work in progress that I'm working on in a collaborative way with a colleague, Dr. Austin Allen, who was supposed to be here. But then he got this amazing invitation to film a documentary that he made 25 years ago, called Claiming Open Spaces, for ASLA, as a part of their celebration of Black History Month. So, he's there instead. This is a film that, if you're not aware of it already, is really wonderful. It is actually a documentary that interviews African Americans about their experience of public parks in Detroit, Birmingham, and New Orleans. It is a really wonderful document, and he was speaking last night about how things don't seem to have changed as much in the past 25 years as he would have hoped.

But, the project that we're working on together has to do with a historic Freedmen's Town in South Dallas, Joppa. When I say it's collaborative, it's not just me and Austin. It's also the residents of Joppa, who are really the main driving force behind the things that we're trying to address within their community, and give them tools to really be the ones who drive a process of thinking about how they are going to deal with issues of historic preservation, development, and huge number of outside agencies, nonprofits, that have an interest in Joppa that have been working with the community for quite some time.

What I want to do is just give you a brief introduction to Joppa and where it is and what it is. And then, I want to talk a little bit about this hybrid approach that we're trying to take that focuses a little bit on object-oriented historic preservation, so historic school that fits in with the previous two presentations really well. Then also, the idea of Joppa as a cultural landscape, which I don't think… it would be really pushing the envelope to try to designate it. But the guidance from cultural landscape treatments is incredibly important to helping the community think about how they want to guide development going forward. So, those are the three things I want to try to cover quickly.

First, what is Joppa? Joppa is, again, it is a historic Freedmen's Town, and it's good that you have the Saving Freedom Colonies brochure going around from Andrea Roberts. Andrea has been a really wonderful resource in coming to Dallas and speaking a couple of times to try to raise awareness of the importance of Freedmen's Towns.

Kathryn Holliday, University of Texas at Arlington

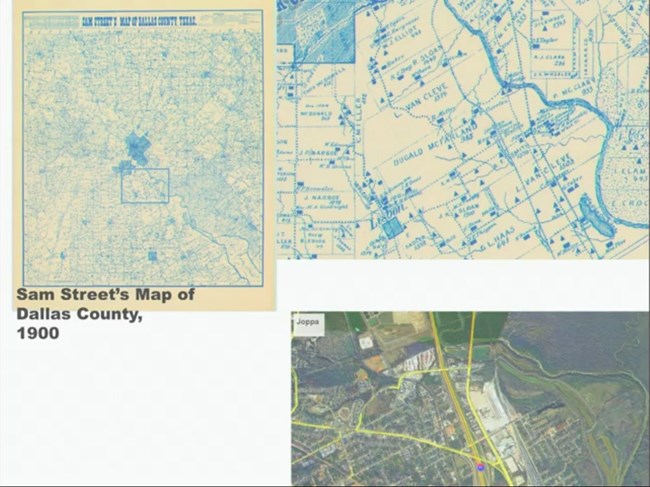

Here's Dallas on the Sam Street's Map from 1900. The section that I'm showing in detail on the right is right here. This is the historic location of the Miller Plantation in the McFarland and Van Cleave surveys. Then right over here off to the right, this is obviously too small for you to see, but there is Miller's Gravel Pit and then a little cluster of residences here that are the origin of Joppa on the edge of that historic Miller Plantation.

You can see here that the boundaries that are established very early on that are the eastern edge is the Trinity River, right here. The western edge is Union Pacific Railroad tracks, which are running right here, and now doubled by I-45. The northern edge is that gravel pit, which is now a giant, cement batching plant. Then on the southern edge, you can see here in this little lake, this is the Rod and Fishing Club. So, private, recreational land for elite whites from Dallas is the southern border, which is now right on the southern edge still, as well as an abandoned golf course and Highway 12. It's amazingly stable in terms of its boundaries. It's also quite isolated even as it's very close to Dallas. And many of the issues that Joppa faces are directly a result of this being a rural landscape that is now a part of the urban sprawl of Dallas.

Kathryn Holliday

And again, just to think a little bit more about the stability, this is a quadrangle map on the right from the early 1960s that shows you, again, the river on one side, now strip mines. On the northern side, the community, now more developed, along a grid with Honey Springs Creek that runs through the middle and out to the Trinity River. And again, that southern boundary of private land owned and operated by white elites. Anyone who knows Robert Dedman and ClubCorp, this is the first golf club that he ever opened, and then Highway 12 here. There's an enormous amount of external development pressure on Joppa now from multiple angles. The new Trinity Audubon Center is down here on the reclaimed strip mine. The new Trinity Forest Golf Club is down here to the southwest where there is as a major golf invitational every year, although it just decided to move back to North Dallas.

There are attempts on the part of Martin Marietta, which now opens the cement batching plant that's up here on the northern side, to expand its operations. Which, I have asthma, and if I'm there on a particular kind of day, you just start coughing the second you get there. There's clear environmental racism in the way that this gravel pit has evolved over time. Last year, there was a denied application to expand that facility. There is, on the southern side, because this land is vacant, there's huge fear that this is going to be developed in a way that's hostile to the neighborhood.

Kathryn Holliday, University of Texas at Arlington

Right, so there's all of these external pressures for development on the exterior boundaries of Joppa, even at the same time that there also is some pressure in the internal landscape of Joppa as well. I just want to show you a one-minute clip of some drone footage that Austin's landscape architecture students took about three weeks ago of Joppa, to give you a sense of where it's located in Dallas. It's very close relationship to the river, which is itself being developed through a regional recreation plan by the city of Dallas and North Central Texas Council of Governments. So, recreational use coming through, the footage is shot right at sunset, which is very dramatic but also a little bit dark.

But Dallas is just right there. It's about six miles south of downtown Dallas, but it is its own little oasis that is deeply, deeply loved by the residents and descendants of the Joppa community. We're going to go a little bit over this. It gives you a general sense. It's a residential neighborhood, very small, working class houses on relatively large lots. In this view, you're looking at the hearts. We're going to come back to this school building, and there's your industrial edge with the railroad tracks, the cement plant, and then I-45 in the distance. Again, tightly-knit, well-bounded.

Kathryn Holliday

One of the things that's happening that brings pressure to the interior of Joppa as well, and not just all of this exterior pressure, is the way that Joppa has been partnered with a number of nonprofits. And it's led to a huge amount of fractured advocacy. For those of you who've worked in historically African American communities, you know that sometimes this can be an issue. There are competing neighborhood associations; there's the Joppa Freedmen's Town Association and the South Central Civic League, which while they may share many of the same goals, do not collaborate at the present moment. There are external nonprofits like Downwinders at Risk, which has been an advocate to reverse policies of environmental racism, along with the Sierra Club of Dallas.

And then, probably the biggest nonprofit intervention has come from Habitat for Humanity, the Dallas-area chapter of Habitat, which has built more than 100 homes in this very small community in the past 20 years. That is fundamentally altered the built environment in Joppa. But it's also fundamentally altered the demographic of Joppa so that a historically African American neighborhood has now become one that has a large Latino population and also has a very large population of immigrants from foreign countries. Habitat. I had been in conversation with Habitat for a couple of years about some issues surrounding the way they have intervened in Joppa in particular, and part of those conversations are a little bit of what I'll talk about.

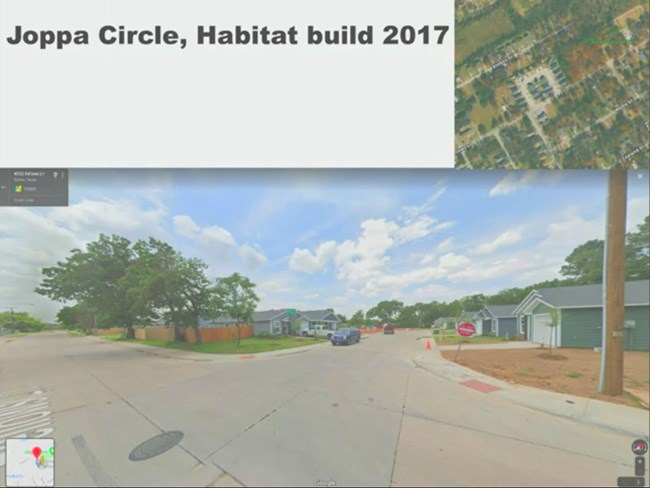

Just to give you a sense for this, this is a build in Joppa from 2017 in which 27 houses were built all at one time. This is a map from Dallas Area Habitat on the left that shows their condition assessment of properties within Joppa. Everything in gray is a vacant lot, so there's a high degree of vacancy and demolition within Joppa, and condition assessment with green being excellent condition, red to undesirable. Habitat has considered this neighborhood, in a way, to be their own project from the ground up. I should also add that Habitat, up until 2018, was the largest developer of affordable housing in Dallas for several years; which, for a nonprofit based on volunteer labor to be the largest developer of affordable housing, I think tells you something about the political and economic culture of Dallas. They did have a major, financial implosion in 2018, however, and so they have not been building quite so much since then as they regroup.

Kathryn Holliday

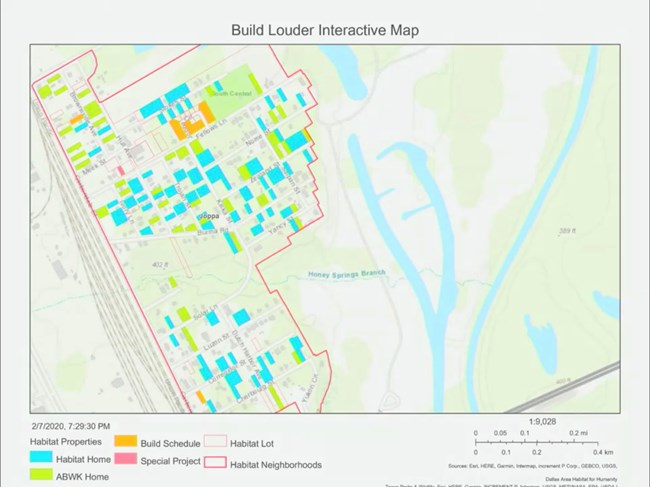

Again, just to reinforce, everything in blue on this map is a Habitat-built home. Everything in green is a home that Habitat has worked on through their brush with Kindness Program, which is a repair program which does not take any historic fabric into consideration. It's just, "Let's get this place fixed." And then everything in orange that you see is something that's currently being built out. While we have this map, I'm also going to point out Habitat also owns all of this land and all of this land, as well as some other plots. And they intend to develop that land in the future when they're back on their financial footing.

Just to give you a sense of what that means, the internal pressure on Joppa really does come from Habitat. Habitat has been the great benefit of being one of the only agencies to actually invest in the community and bring new housing and new residents to a community that had been in decline by many measures, in terms of ex-migration and loss of housing. But on the other hand, when you look at the way that they're developing, particularly this last build, which is a cul-de-sac right here with very dense housing… I'm just showing you one view down the street, here, from Google Street View. It's a one way street. They cut all of the trees down. The street is about twice as wide as the traditional streets of Joppa. There are high-privacy fences. There's sidewalks. The curbs are different. I mean, everything about this build is completely different than what exists in Joppa. This is something that the residents, especially long-term term residents really don't like.

As much as they want to see investment in their community, they want to have a greater voice in what it looks like. In all of the things that they talk about, they talk about scale, they talk about trees and saving historic vegetation. Everything that they talk about is the same thing that's in the cultural landscape guidance. That's just no prompting; that's what they care about. They want the feel of their community to remain the same. So, there's been a pretty good opportunity to have conversations about how to potentially create some way of codifying what the community would like to see in a different kind of overlay.

Kathryn Holliday

Here's these two approaches: the first is this object-oriented historic preservation. There's not much in Joppa that really seems to qualify, especially under the lens of integrity. There's huge significance, but in terms of integrity, there's some real challenges. There's almost nothing that doesn't have huge intervention either in the build fabric or in the landscape of Joppa, which we'll look at in a minute. But there's one potential candidate, which is the Melissa Pierce School. I'm showing you one images of the school here.

Melissa Pierce School was the segregated school that was built in Joppa in 1953. It was part of the Wilmer-Hutchins Independent School District, which is south of Dallas ISD. It's now a part of Dallas ISD. For anyone who keeps up with school district news, Wilmer-Hutchins ISD is one of the most troubled ISDs in the history of the state. It was actually closed down and subsumed into Dallas ISD, which gives you a sense of how troubled Wilmer-Hutchins ISD was. All of their records are now gone because Dallas ISD did not really keep them. So, information about the school is mostly coming from its graduates. And Melissa Pierce is a part of a big program in Wilmer-Hutchins ISD that, like all of Austin ISD that we just heard about and many other ISDs across the state, intentionally tried to maintain a segregated school system by building out separate-but-equal facilities after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. In Wilmer-Hutchins ISD, they built multiple elementary schools, they built a middle school, and they built John F. Kennedy High School from the mid-50s through the early 1960s, this is a segregated African American school system.

Melissa Pierce is a little bit different than many of those other segregated schools in Wilmer-Hutchins ISD because the land for the school is actually given by a resident of Joppa, Melissa Pierce, who many residents would call as being Auntie Melissa. She was someone who was a benefactor to the community and a real pillar of the community. She donated the land to the school districts with the charge that they would build a school for her neighborhood. The only reason that Joppa got this school was that someone gave the land. Otherwise, there probably would not have been a school in Joppa. And it's named for her, a member of the Joppa community.

Kathryn Holliday, University of Texas at Arlington

Therefore, some of the ways that we think about the school; it operated between 1953 and began to close down in 1968. There are a number of ways that students went to school here, either as an elementary school, or K-12, or just a middle school, as Wilmer-Hutchins ISD tried to create the impression of a separate-but-equal system in different ways during that 15 years. But after it closed and was sold by the school district in 1974, it became a church over a number of years. And it's been now empty for about 10 years and is in pretty difficult condition. That's, when you're looking at the back facade of the gymnasium here, that's why you're seeing those crosses, is that there is an adaptive reuse of this school building into a church building. It was occupied by two or three different churches.

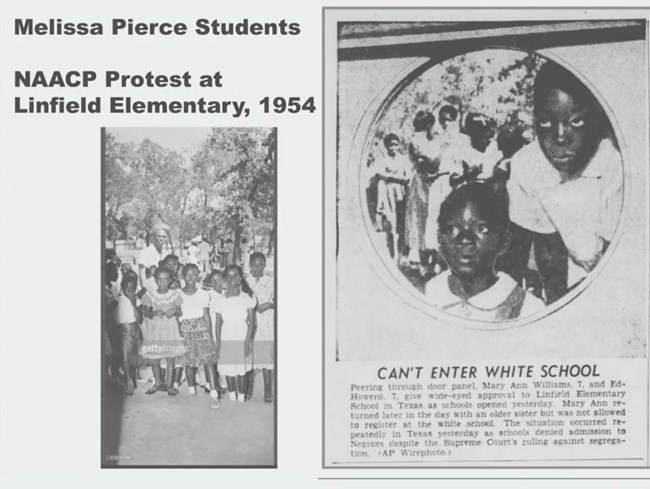

The school is also significant because Joppa was such a tight-knit community. The NAACP organized a protest where Melissa Pierce students actually went to Linfield elementary school which was the white elementary school in Wilmer-Hutchins ISD, to protest and ask for admission to Linfield Elementary. This is where Greg Smith was very helpful. When I first got aware of the school and residents' desire to keep it and preserve it, the first thing I did was I reached out to Greg and to David Preziosi of Preservation Dallas and say, "Hey, is this school on your radar?" It was actually on the radar because of a Section 106 review for high-speed rail. There's a little bit of documentation that I'd been working to fill in some more since this initial contact with the school in 2017.

The Joppa school operated on a separate calendar from the white schools in Wilmer-Hutchins ISD because children who went to Melissa Pierce were still picking cotton in the fields through the early fall. So, their school didn't open until about six weeks after the Linfield Elementary did. There was a protest organized in September 1954 where children went to Linfield and said, "Hey, our school is closed. Will you please let us in?" And they were denied admission. So, Melissa Pierce School is important to the residents of Joppa, but it also is a significant setting for the way that we think about the way that segregation worked in Dallas.

Kathryn Holliday

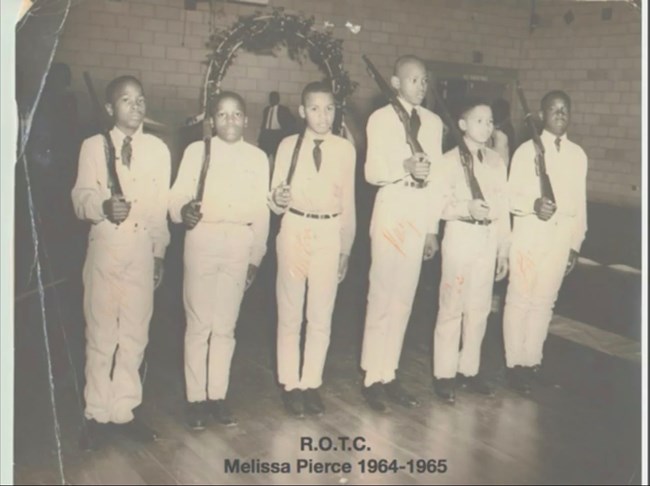

I think this gets to the point of Kim's question earlier, which is; How do we interpret these places? I think especially for a white outsider, this school looks like something that you would think of as a symbol of racism and segregation. But to people who went to this school, it's something very different. And they take enormous pride in the fact that this school was theirs. It was built on their land, that there were significant opportunities for ROTC. This is a photograph that was shared by Gwen Jackson, a graduate of the school with me. There were field trips. They had professional teachers. Before they got this school, they had gone to school in the church that was next door, and they had sat in pews with books on their laps. So, this school is actually a symbol of success and progress. And so kind of flipping the mirror on how we think about the narrative is really important in determining how we interpret these sites.

The school, while we have an initial determination of eligibility because of its adaptive reuse and several changes across the years, we'll have to see. Habitat owns this school building, and I've spent a couple of years urging them to think of historic preservation as an option. Anyone who's worked with Habitat in Texas, in particular, knows that they say, "We don't do historic preservation." I gave the plenary address to Habitat across the street over the summer for their Texas Summit and talked about historic preservation and place memory to try to get them to think along those lines and it was a productive conversation. Just last week, they did hire a preservation architect to at least do an initial look at this school to see if there's some potential there for some adaptive reuse. My fingers are crossed that that's going to head in the right direction. But the other piece, of course, is that this school sits in the middle of a much bigger community that I showed you a little bit of an overview of, and this is the landscape that extends out from the school and in towards the community.

The real issue is how is this area going to develop? One of the challenges to the idea of making any kind of historic district or making this a historic site, is that people who live in Joppa want it to develop. They don't want this land to remain vacant. They want development. They want investment. They want the investment that was denied to them through Jim Crow, through the civil rights era. They want that investment now. They just want to be at the table to talk about how that investment is really going to happen.

So, this is where Dr. Allen and his landscape architecture studio are really coming into the mix. I will say that as a non-representative of an agency of any kind, I'm not a city official, I don't work for the state, I don't work for the Park Service. That's actually really helpful in having these kinds of conversations because I can't decide anything. There's no meeting that we have in which any decision is being made. It really is an open conversation, and I can't emphasize enough how that is important. I am an educator. I'm there to listen, and I'm there to try to support the process. For anyone who works for an agency, you're perceived as someone who has power and can make a decision. So sometimes, turning to those of us who, well I can't affect anything, that can be a really positive thing to bring into the mix in particular. That's where we have been going through a number of workshops.

I have meetings monthly with Habitat and Latosha Herron-Bruff, who's their Associate Director for Community Outreach, with Clarence Glover, who is a Dallas historian of African American experience in Dallas, with Austin Allen, my colleague in landscape architecture, with a councilman for this district from Dallas to try to talk about strategies. But then on the other end, we have meetings with the community as well.

This is the meeting of the studio from just about 10 days ago in which we started the process of doing essentially, we didn't call it this, but it's really a cultural landscape survey and analysis of what's valuable to you in your community. What are the places that are important to you? Circle them on a map. Let's go walk to them and take pictures of them. Let's think about what it is that you value about the physical landscape of your community. And again, we can't deliver anything, but we did deliver a menu that the community has then taken to a meeting with their councilman. So, just being there as a supporting mechanism to provide the language and the things that will sound like things that people in positions of a policy authority will recognize, is hugely important.

Kathryn Holliday, University of Texas at Arlington

I'll just point out one or two things here. This is a typical street intersection in Joppa. The streets are long and straight and narrow, and they're lined by historic vegetation. Most of the driveways are currently unpaved in the historic parts of the neighborhood. On the left, here, when you see Meek Street heading off to the left, there are unpaved streets still in Joppa as well. Joppa didn't get storm sewers until the 1970s. It is an area that was deeply underserved by civic infrastructure for a long time. There's a woman who lives on Brownsville Street who said, "You know, I've lived here for 72 years. All I want is for that street to be paved before I die." So, a paved street, changing that landscape is really important. We don't want to keep the dirt road that gets muddy all the time. But the issue is that Habitat owns the land here. For them to pay the street according to current city code, it has to be wider. That means they have to remove all of the historic vegetation to widen the street and make this big, wide street. It's very different than Brownsville.

So, what we want to try to suggest is a stabilization overlay, the calls on cultural landscape guidelines, and justifications for saying, "No, don't remove the historic vegetation, create some guidance that allows narrower streets in Joppa. We're involved in this conversation with the city about what can and can't be done. Habitat insists that the reason that they made that cul-de-sac that's one way, was that the city required them to. I think everybody knows that a big, rich developer can get every variance that they want. So, the question is how to create an argument for a variance within Joppa without the big bucks the developer can bring to the table.

And me, as the historian, my role here is often just to go find documentation. And I was lucky to find that in the 70s, when they put in the storm sewers in Joppa, they did very detailed surveys, of course, along the way of where they're going to put the storm sewers. So, we have some documentation of the kinds of vegetation. This is a pig pen along with the chinaberry trees, and the boat arcs, and where the dead trees are, and the live trees. It's incredibly detailed all along the path that each of these sewers was actually put in. We have a pretty good reconstruction for some portion of the neighborhood about what the historic vegetation looked like, what the agricultural uses of land in Joppa were. No one wants the pig pen to come back, but there is this desire to think about agriculture in a new way as being a part of what the future of the neighborhood is without the pig pen.

Kathryn Holliday, University of Texas at Arlington

We also have, in the city surveyor's office also from the 70s, this incredibly detailed survey of who owned what land, which is remarkable, kind of snapshot in time of who owned every single lot in Joppa in that time period. So, we have an opportunity here to also go back through oral histories. I've partnered with bcWORKSHOP on some storytelling workshops in Joppa to go back and try to reconstruct what did this place look like in a period before the losses and demolition really started, and to give that back to the community as their information and their heritage.

What I want to close with is this larger idea this is really a hybrid approach. It's not necessarily, really, historic preservation of cultural landscapes because that's not the goal of the community. They don't want to freeze anything. They actually want to develop the open land that you see here around the school. The landscape architecture students are going to do some workshops about what do you want to see in that land? Do you want a community farm, which is one suggestion. Do you want a playground? What do you want to see in that space? There are opportunities to try to talk to Habitat about how to be a developer in a historic community, so that you don't take this one-size-fits-all of a nonprofit that does amazing work. But then when you get to individual communities like Joppa or other neighborhoods, especially in Dallas that I'm most familiar with for their work, it's not one-size-fits-all. You can't just plop the solution down in every single place and have it be the same.

The final thing as well, is for Habitat, also as a developer in an agency that intervenes in many of the neighborhoods that all of us work in, for them to think about their role in those neighborhoods in a really different way. They've often said, "We just build houses. We don't build communities. We're building houses. We're providing affordable housing." But especially in a place like Joppa, what you can tell is, they have built a community. They've built half those houses, and they've changed who lives in the neighborhood. They have built a community. So when the neighborhood says, "We want to save our historic school and turn it into a community center." We started the conversation two years ago with, "We don't do historic preservation, and we don't build community centers." But across the past few years, the conversation has shifted a little bit, and they're open. They're open to that conversation.

I'm going to echo a lot of things that many other people have said, which is flexibility, being open to lots of different points of view and lots of different conversations. And I think all of you know, more than I do in many ways, is it takes a lot of time for these things to happen, and patience is important. Thank you very much. If there any questions, I'm happy to answer.

National Park Service

Questions

Speaker 1: I have a question for both you and some of the other earlier papers. As you're dealing and you're talking with schools about preservation and the historic interest, how are you utilizing the Antiquities Code? I know it doesn't go as broad as Section 106, but within those efforts?

Katheryn Holliday: That's a great question, and in this case, we haven't. So, I would just say we haven't. I don't think it's really necessary in this case, although it might be for others. I don't know. I think we have other tools that we can use that are more appropriate for this particular case.

Speaker 2: There are probably no federal dollars involved.

Katheryn Holliday: And there are no federal dollars… I mean, that's a main thing.

Speaker 1: Well, Texas has state antiquities over them that protects everything on state property and state lands, or municipalities that are a political subdivision of the state, so city's counties and ISDs. So, anything that that getting state funding, that's on state and city property. It's one of those areas where it does more for direct effects rather than indirect, so it doesn't encompass landscape quite as well as a Section 106 would. But from that direct effect to historic structures to buildings to fields to schools, there are some compliant requirements. If those buildings are going to be run down or [crosstalk]. That's why I was thinking of [crosstalk] if that covers with a school, trying to preserve a community center, and those kind of things.

Kathryn Holliday: Again, I think, in this case, we have other tools, and it's because there are no federal dollars. But there is also this property is owned by Habitat for Humanity. So, they can do whatever they want. There's no designation of any kind for anything. The neighborhood has long fought any kind of overlay. Largely because of this fracturing, there hasn't been any consensus. The one thing that all of these groups agree on is that they would like to see the school become a community center. So, it provides an opportunity to bring groups with conflicting interests together to try to create a common conversation around the shared goal.

Speaker 3: I was just going to say real quick, in the case with Anderson, it's my understanding with the Antiquities Code that you have to protect a State Antiquities landmark for above-ground structures. It's different than archaeology. And to do that, you have to be eligible for listing, and then afterwards [inaudible], so there are some rules and hurdles [crosstalk]. So there're multiple hurdles before Anderson would even be able to use the Antiquities to have something there.

Kathryn Holliday: Well, it's more like if they have a plan to change the build and alter it in a way, and it's considered, and it has to be reviewed within in that. There's a project that's planned that could impact the destruction of the school or those kind of things, you have to at least review it within the code. But for taking it a step forward for that protection, we have to use a SAL listing.

College of Architecture, Planning, and Public Affairs at University of Texas at Arlington

Speaker Biography

Kathryn E. Holliday, Ph.D, is an architectural historian whose research and teaching focuses on the built environment in American cities. Her background is in architecture, art history, and environmental studies and she brings this interdisciplinary approach to the classroom and to her writing. In the past, she served on the State Board of Review for the Texas Historical Commission's National Register programs between 2009 and 2015 was also a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Architectural Education.