Last updated: December 30, 2021

Article

The Lenape: Native inhabitants of the St. Paul's area

The Lenape: Native Inhabitants of the St. Paul’s area

Before the arrival of the European colonists in the 1600s, the area around St. Paul’s Church had long been the ancestral home to various bands of native peoples. They were part of the broader group of Lenape or Delaware Indians, and spoke a tongue belonging to the Algonquian language family. They have often been mistakenly referred to as "Siwanoy," a name they almost certainly never called themselves, but which nonetheless has become deeply entrenched in our literature. Sometimes scholars also call them "Munsee" -- after the name of the Lenape dialect they spoke. However, like other native groups, they tended to call themselves by the names of their local villages.

The Lenape were semi-sedentary and peaceful, having settled in their homeland no later than 1,000 years ago and probably much earlier than that. Indeed, archaeologists tell us that people were living in the northeast for at least 12,000 years but with the absence of ancient writings there is no way of knowing what these earlier groups called themselves. The Lenape who lived here in the 1600s were mostly clustered along the Long Island Sound and its inland rivers from today's Westchester County to the Bronx.

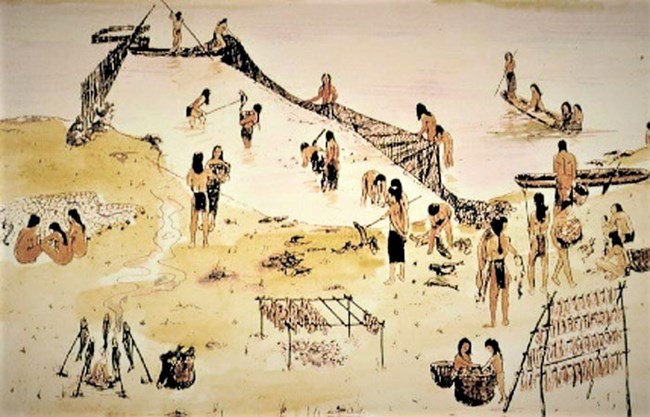

The Lenape enjoyed a traditional and stable lifestyle in established villages, subsisting through hunting, fishing, gathering, and horticulture, although their lives were periodically interrupted by limited warfare with other regional Indian groups. A village generally comprised a cluster of several wigwams -- round or oval shaped bark dwellings with an aperture in the roof serving as a chimney. Some could be as long as 60 feet and hold several families. Since they lived along the waterfront, the diet of these Lenape groups was dominated by shellfish. Mussels, clams, and oysters were dug from the beaches and shores on a daily basis.

The Lenape also refashioned elements of the shells to create beaded belts known as wampum, a highly valued commodity. The large nets crafted by Lenape to catch spawning fish -- alewives, shad, sturgeon, and other species -- were weighed down with stones and spread across the mouths of streams, yielding a considerable harvest each spring.The Lenape supplemented their diet with flesh cut from deer and elk felled with finely sharpened, triangular stone arrows. Deerskin was also the principal material for clothing. Several times a year the Lenape burned sections of the woods to maintain the meadows and habitats upon which the herds of game animals depended.

Women were responsible for most of the agriculture, growing primarily corn, beans, and squash, and gathering nuts and berries from the fertile local forests. In a society where heredity was determined through the female line, women enjoyed considerable respect.

A Lenape leader, often referred to as a sakima (the word sachem comes from a related Algonquian language) was recognized, but they lacked the coercive powers of government enjoyed by most European rulers; instead, he had to persuade other band members to follow his policies, leading to a perhaps more democratic society. A sakima had many tasks: exercising ceremonial duties, settling minor disputes and managing relations with other tribes, and eventually also with Europeans. Village members could reject or reverse previous directives.

In what emerged as an important source of misunderstanding with the Dutch, and indeed with most European settlers in the New World, the Lenape recognized land as the communal property of the village. Land could be parceled out to a family; it could be re-distributed to another clan as necessary and required, and individuals and groups could enjoy use rights on it. However, the Indians had no understanding of individual private property during the time when the first European settlers were arriving in America.

When war was declared, a special group of men recognized for bravery and martial skill led the band. These war captains temporarily superseded the sakima and his council, making military decisions which could also include crafting peace terms.

Dispersion & the Continuity of Culture

The intrusion of the European settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries disrupted traditional Lenape lifestyle patterns that had sustained the local bands for hundreds of years. These disruptions were reflected through environmental, cultural, and demographic changes that produced disastrous results for the Indians. However, concerted efforts in the 20th century by Lenape descendants generated a renewed appreciation of traditional lifestyles and a restored connection to lower New York.

Thousands of natives died from epidemic diseases introduced into the region by the European settlers in the 1600s and 1700s. Lacking any natural immunity to smallpox and other contagions, the Lenape, and other native groups along the eastern seaboard, contracted these diseases through contact with the colonists and perished in alarming numbers. The fur trade with the European settlers also weakened traditional Lenape culture internally. In return for obtaining beaver and other furs for the Dutch and English traders, the Lenape received metal pots, knives, axes, and arrowheads, among other goods. These durable metal items were in many ways superior to Indian stone tools. But through use and reliance on these tools, the natives lost the ability to fashion traditional crafts they had cultivated for centuries, and became completely dependent on the colonial traders, who often used this dependency to exploit the Indians. Competition for the opportunity to supply the merchants with the animal furs also produced conflict and wars among the local Indian bands.

Fraudulent land deals with the European settlers, coupled with cultural misunderstandings about the concept of private property, caused the Indians to lose access to large tracts of ancestral land. The settlement on local natives’ lands by Dutch and English colonists -- a movement which colonial governments were unable or unwilling to deter -- further altered the landscape. Europeans required grazing areas for their livestock, and they cut down forests and established farms, destroying hunting areas and valuable food resources for the local bands of Lenape. By the late 1600s and early 1700s, through wars, lethal epidemics, and environmental alterations, the formerly thriving Lenape villages had been reduced to broken communities, beginning an exodus by the Indians.

In the initial departure, most of the Lenape bands migrated westward to the Susquehanna and Ohio Valleys, where they amalgamated with other displaced Lenape and Eastern Woodlands groups that had also been driven from their former lands. After the American Revolution, the descendants of the Lenape of New York scattered in many directions. Some found refuge in Ontario, Canada, and some of their descendants are still there; other Lenape traveled across the Great Plains and by the late 1860s reached the designated Indian Territory, which has since become the state of Oklahoma. Another group that represented the descendants of the Lenape of our area eventually settled in Wisconsin on the Stockbridge-Munsee Reservation, where they can still be found.

Through all the dispersions and disruptions, expressions of cultural heritage and traditional practices diminished, but were never fully extinguished. A concentrated effort in the late 20th century to reinvigorate earlier folk patterns has achieved a considerable degree of success. Lenape descendants and academic historians organized conferences to study Lenape language and traditions and encourage a regeneration of these exercises.

A Lenape elder from Oklahoma, Touching Leaves Woman, played a particularly important role in this renewal. Among the last people who could still speak the Lenape language, she had been schooled in the traditions of the nation. Touching Leaves Woman worked with historians and linguists to record Lenape language and traditions and traveled to locations of Lenape descendants to create interest in a cultural revival. In the 1980s and 90s, descendants were organized to visit New York to become acquainted with the land of their ancestors. Annual powwows on Lenape reservations help maintain tribal identity and traditions. Exhibitions and presentations disseminated the story of the former residents of the area to the general public. These developments have helped to reaffirm the history and heritage of the original settlers of the St. Paul’s vicinity.