Last updated: October 30, 2024

Article

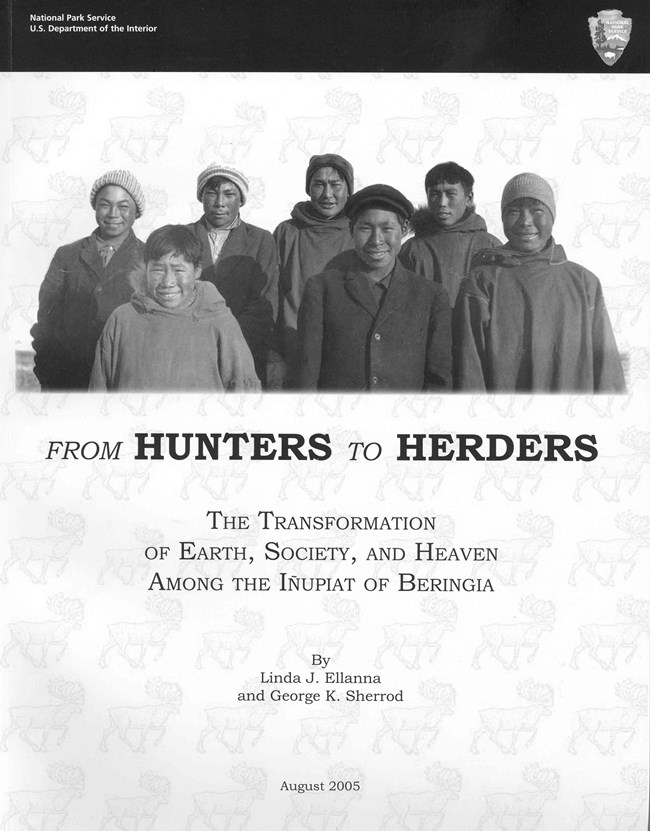

The Hope and Promise of Ublasaun: A Herder's Story

By Linda J Ellanna and George K. Sherrod

It was the spring of 1918, and the world was embroiled in the closing phases of World War I. This was the year that the tide of the war ultimately would turn to favor the allied forces. During the coming winter, however, 20 million people around the world would succumb to a devastating epidemic of what was termed “Spanish influenza.” While the war, removed by geography and culture from the day to day concerns of most Iñupiat of Northwest Alaska, may have had little direct influence on their lives, the influenza epidemic to come was to affect everyone. The tumultuous climate of the year passed unnoticed in the short life of Thomas Makaiqtaq Barr’s first son, one-year-old Gideon Kahlook Kunautaq Barr. (“Makaiqtaq” was spelled many ways by White teachers, such as “Mukaktik,” “Mukritruk,” and “Mukituk.”) Thomas’s wife Emily had given birth to Gideon in the northwestern Seward Peninsula village of Shishmaref on July 21, 1917. Shishmaref was the location of women healers and midwives to whom Iñupiat turned for assistance when giving birth. One of Gideon’s Iñupiaq names, Kahlook, was bestowed upon him as a namesake of a deceased relative of his father. His other Iñupiaq name, Kunautaq, was that of his father’s father.

It was in 1918 that Thomas Makaiqtaq Barr built a house at Ublasaun, planning to abandon the family’s former home at the winter camp to the southeast. This winter camp was called Qivaluaq by the Iñupiat, but known as Kividluk or Kividlo to the few White people in the world aware of its existence. Nearby Qivaluaq was the associated settlement of Salliñq, or “a place where there is a lagoon behind and a beach coast outside.”

In 1918, as it had been for millennia since the end of the last “ice age,” the Seward Peninsula reached out across the narrow waters of Bering Strait toward the Chukotsk Peninsula of Siberia. The windswept tundra of the northwestern Seward Peninsula lay behind a coast line that often was pounded by the crashing waves of the Chukchi Sea. In the spring of 1918 a multitude of Iñupiat settlements and seasonally occupied camps dotted the shores of this landmass, dispersed opportunistically among its many lagoons, inlets, lakes, streams, sandy bars, islets, and islands.

Spanish influenza would reach the area by late fall of 1918. Some settlements north and east of Shishmaref were spared, however, largely due to a quarantine enforced by local Iñupiat with the use of firearms. The people of Cape Prince of Wales to the southwest and other settlements to the east in the interior of the Seward Peninsula and to the northeast in the Kotzebue Sound area were not so lucky, as the epidemic forever changed the distribution of the Iñupiat of Northwest Alaska, touching everyone in some way by taking the life of a relative, trade partner, or acquaintance.

When Thomas began to construct his house at Ublasaun, he knew from the rich oral tradition of his people, from his experience camping there while fall seal netting, and from the remains of ancient houses—occupied by people who had not yet acquired metal implements, but who used large, pecked stone net sinkers and indigenous pottery—that his was not the first winter settlement at this location.

In 1918 Ublasaun remained a very productive site for fall seal netting by the Iñupiat of the area. Every household had a few fathoms of seal-rawhide, eight-inch mesh net. Before freezeup, people cooperatively netted the much needed and desired spotted seals (adults and pups), ugruk (bearded seal), and, at times, beluga (white whales). Each household’s net was attached end to end until the greater net was composed of three or four of the smaller panels, weighted to the bottom of the sea by stone sinkers. The seals taken between the knots became the property of the family in whose individual net they were caught. Seals that had drowned and washed ashore down current from the net became the property of whoever discovered them in the morning on the beach. Therefore, early each morning, children raced from their houses down the beach to find seals that had washed ashore. The large net was checked by adults in umiaqs twice daily and monitored constantly to ensure that the large ugruks or beluga that might become entangled in the mesh could be dispatched before destroying this piece of cooperative technology. Periodically, the large net was brought ashore to dry, lest it become too soft to be effective. Some of the seals were stored whole in underground caches, where they soon froze, and were processed during the coming winter as needed.

But 1918 was the first time that Ublasaun was to serve as a winter village for Iñupiat reindeer herders, whose lives had predominantly depended upon the bounty of the sea and the wild herds of caribou that once roamed the tundra.

Both the seeming disappearances of the caribou and the arrival of imported Siberian reindeer from Chukotka were phenomena relatively recent in the tradition of the Iñupiat. In the next two years, Thomas’s brothers, nephews, his apprentice Gordon Dimmick (Qiziilaaq), and some other relatives and associates moved from Qivaluaq to Ublasaun, where they remained during the winters until 1925. Ublasaun was chosen as an opportune site for the winter camp, since the herd kept straying away from Iñuirniq (Espenberg River) and heading southwest. Ublasaun was closer than Cape Espenberg to the herd’s previous calving grounds near Qivaluaq. Reindeer does, like caribou does, try to return to the place of their birth to fawn each spring. Additionally, there was good moss for winter food near Ublasaun. So the herders decided to move there to remain closer to their animals.

Seven more semisubterranean houses were constructed by the people who moved to Ublasaun following Thomas and his family. This is the community that Thomas’s son, Gideon, remembered as a young child.

A description of the distribution of people in the eight houses at Ublasaun and their relationships contributes a breath of life into this setting. Thomas’s semisubterranean house was the first dwelling on the southwestern periphery of Ublasaun, on the east bank of a small creek that drained nearby tundra lakes. Besides Thomas, his wife Emily Paizuzraq Kiyutelluk (Qayutialak) and their three daughters and two sons—Fannie, Bessie, Mary, Gideon and Elijah, respectively—lived together in this, the largest house at Ublasaun. Thomas’s youngest brother Peter Kahlook (Qauqluk) Barr, who as a child had been adopted out to another family, his wife Bessie Sikinguaq Okie, and their three children Roy, David, and Lydia resided two houses up the beach from his eldest brother’s home. The unmarried apprentice herder Gordon Dimmick, whose father was from Kivalina and who subsequently married Peter’s wife’s sister Mary, lived in a small house situated between those of Thomas and Peter.

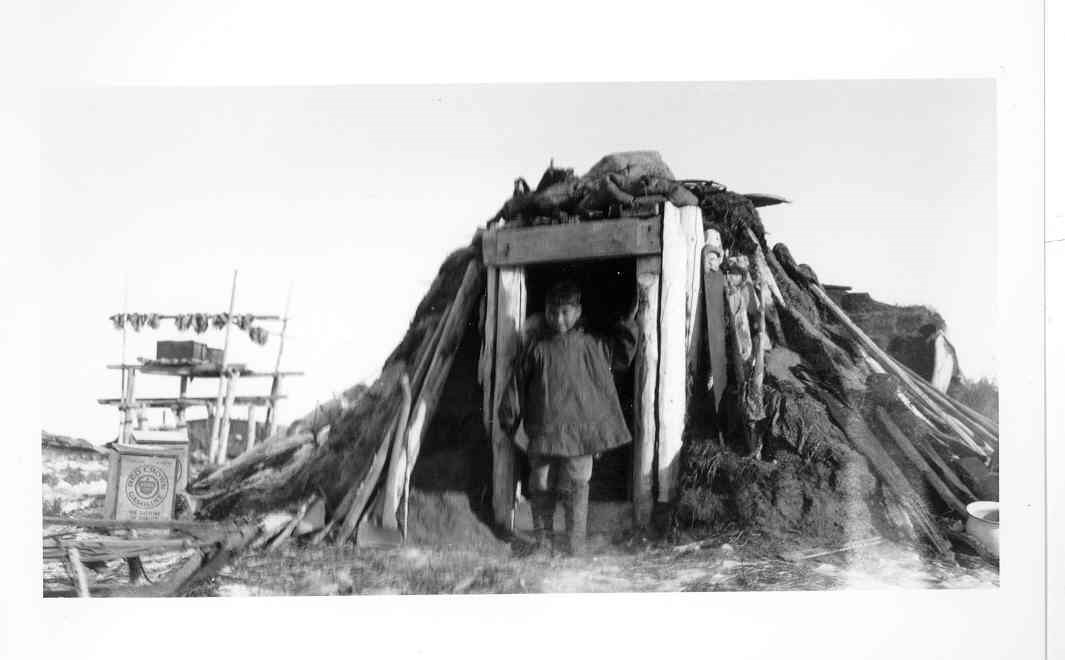

Thomas’s other brother Gilbert Sublaq Barr lived at the northeastern most periphery of Ublasaun with his wife Rosie Umisaaq, their daughter Lillian, and their three sons Edward, Isaiah, and Jessie. There was a strong bond of kinship between Gilbert and Thomas, who wanted to live, herd, and travel with each other. Rosie’s stepfather Umiaq and mother Aguviuna lived in the shadow of their daughter’s house in the most traditional style structure in the settlement, reminiscent of the dwellings of people who occupied this site before iron came to the Iñupiat.

Three other houses were positioned between those of the brothers Gideon and Gilbert. One was the home of two young men Adrian (also called Edwin) and Walter Barr. These young men were brothers whose deceased father Ahvalook was the eldest brother of Thomas, Gilbert, and Peter. The second was the home of widower Moses Qiluq and his adopted son James Kivetoruk Moses. Moses was from up the coast. His now-deceased wife was Thomas’s older sister Quganaq. The third dwelling was inhabited by Lloyd Koonuk and his first wife Margaret, who was James Moses’ sister, and their three children, Rudolph, Ernest, and Daisy. James’s biological father was the brother of widower Moses Qiluq. Lloyd Koonuk, originally from Arctic River southeast of Shishmaref, was the brother of the affluent reindeer herder William Allockeok (Allagiaq).

The total population of Ublasaun in the early 1920s was approximately 30—a fairly large winter settlement even then, since members of the village dispersed to Cape Espenberg and elsewhere during summer months. This community, however, was not large enough to have a qazgi or men’s house.

Except for Umiaq’s and Aguviuna’s more traditional domicile, the houses at Ublasaun were transitional between the semisubterranean homes found at Shishmaref and throughout Northwest Alaska in the recent Iñupiat past, and frame dwellings at Deering, the dominant house form of the future. In 1920, from the exterior, the village resembled several small hills with protruding smokestacks. A small skylight made of the translucent stomachs of walrus or of glass was set in the apex of each of these sod-covered mounds—this skylight being large enough to emit light but small enough, hopefully, to deter the raiding paws of a polar bear.

Gideon remembers that the family’s 10-by-18-foot house at Ublasaun was constructed of driftwood. The little scrap lumber available at Cape Espenberg was used to build the single bed for Thomas and Emily. Gideon and his siblings slept on the floor. The plates and cooking utensils were stored in the corner next to the stove. Each house had a single door connected to the living room by a long hallway. Food, clothing, hunting implements, and other items were stored in the tunnel-like corridor. While serving as a storage shed, the tunnel functioned to buffer the living quarters from the arctic winds and cold.

Photos by Edward Keithahn, circa 1923, courtesy of Richard Keithahn and the National Park Service (neg. 023)

There were numerous elevated and subterranean caches around each dwelling in or upon which each family stored food, tents, hunting gear, clothing, and other items essential for life in the Arctic. The elevated caches were constructed of four driftwood poles 8 to 10 inches in diameter and 20 to 25 feet long, firmly implanted in the tundra. Between these uprights, cross pieces were attached that, in turn, supported one or more floors. The first floor was positioned as low as seven feet above the ground with others placed five to six feet above the one beneath it. Kayaks, spears, nets, ice scoops, and other implements for harvesting resources were stored on the lower level. Animal pelts wrapped in ugruk or walrus hides were placed on the upper tiers to protect them from the elements. Families with umiaqs stored them upside down for the winter on elevated platforms beyond the reach of hungry canids. However, for most of the time, the families’ work dogs were staked in proximity to their owners’ dwellings. From a distance, the elevated caches and overturned umiaqs on their platforms provided the only hint of occupation, since the houses appeared as mere knolls in an otherwise windswept landscape. Worn paths in the snow linked the clusters of domestic structures to each other, forming the physical manifestations of a community.

Gideon described the differences between the interiors of the old house of Umiaq and new houses at Ublasaun as he remembered it in 1990:

It [an old house] has a kitchen and a living room, and hallways—a little short hallway and a storage shed. Those were used and made before they start using stoves in the house. That kitchen got to have—the top of it has to be built up a little higher than the living room because the smoke has to go out. And inside the living room it is only heated by a seal oil lamp, and they also cook some and melt some snow on those seal oil lamps. You can tell real easy if it’s an old house. There would always be on the right side coming in that’s the kitchen there and the living room over there. That is only heated by seal oil lamps. That’s they way they were built.When we built these houses, we lived modern way. We got stove, cast iron stove, and a smokestack. Nice and warm in the house all the time. And the only seal oil lamps we ever used was in the storage shed during the winter. And we were using kerosene lamp at first and then, finally, these gas lamps come out and that’s when we start using the gas lantern, which is even too bright. [Barr 1991e]

The floors of the structures were planked with wood, except for the cache. A rawhide loop was kept near the covered opening in the ceiling for snaring polar bear legs if such animals attempted to reach through the stomach or glass skylight. If a polar bear leg were caught with the loop, the Iñupiat tightened the tension on it and the loop was attached to a house beam. Then the men exited the house with weapons and killed the bear.

Photos by Edward Keithahn, circa 1923, courtesy of Richard Keithahn and National Park Service (neg. 161).

It was not uncommon on a winter day to see children sliding down steep banks with fleshed seal skins ready to stretch. The children “curved the front up” and they really slid fast. They also used slabs of ice as sleds if seal skins were not available.

In 1918 Thomas, Gilbert, and Peter; their paternal nephews Adrian and Walter; James Moses; and Lloyd Koonuk, all had reindeer. Dimmick was Thomas’s apprentice herder. While each man had his own deer identified by a unique earmark, the animals were kept collectively in a single herd. An earmark was a pattern cut into the ear of a fawn while it was still with its mother and was used to establish ownership of the animal. By consolidating the deer, these related owners cooperatively herded, thereby caring for their deer 24 hours a day—a technique called close herding—while alternatively pursuing hunting, trapping, and fishing. Herding involved ensuring that the animals did not stray or fall victim to predators such as wolves, wolverines, and polar bears. While the deer had to be watched year round, the most critical time was in the spring when the does fawned.

During the months at Ublasaun before spring fawning, the herders engaged in trapping furbearers—primarily red and arctic foxes, but also mink, land otter, lynx, and wolverine. As prices for pelts in the early 1920s ranged from $22.50 to $250 for a blue or silver fox, trappers potentially were able to earn more in three months than a government teacher/reindeer agent did in an entire year. Being in the vicinity of reindeer improved the prospect for a successful trapping harvest, as foxes were drawn to the herds in search of food in the form of carrion.

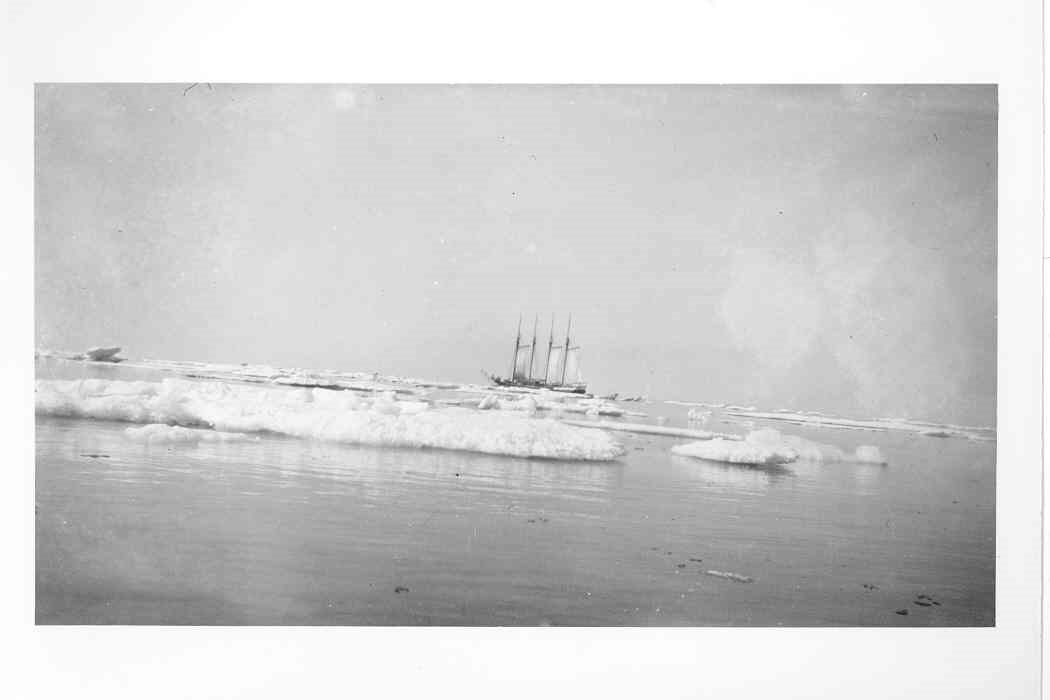

White traders aggressively sought the pelts of the Iñupiat trappers. In the summer, small boats as well as four-masted sailing schooners anchored off Cape Espenberg northeast of Ublasaun, trading dry goods, ammunition, and groceries such as flour, sugar, milk, coffee, and beans for fox pelts. Some traders developed long-term relationships with the Iñupiat similar to indigenous trading partnerships. For example, while wintering at Ublasaun, Thomas and the others traded with John Backland, the owner and operator of a large schooner. In subsequent years they traded with Backland’s son. The high value of the pelts induced some fur buyers to undertake risky, extensive winter travel by dog team to beat out their maritime competitors. In 1923, White fur buyer John Swedler visited Ublasaun. Not only was Swedler the first White man Thomas’s six-year old son Gideon remembers seeing, but the trader also taught the boy his first English word, “dollar.” While Gideon watched, Thomas traded fox pelts for pieces of green paper. Gideon was fascinated by the paper money with pictures of strange looking men he didn’t know.

Trader Swedler traveled by dog team from Candle and Buckland. He acquired his Iñupiaq name, Kimoqtetoghoruaq or “a person that has eaten a dog,” because of a time when he was caught in a storm and was forced to consume one of his animals to survive. Because people at Ublasaun traded in the winter with overland travelers and in summer with merchant vessels, there was less reason for these Iñupiat to go regularly to any other settlement to obtain Western goods. However, they exchanged their dollars for goods periodically at the trading post at Deering.

In April, when trapping had come to an end, the Ublasaun families moved to spring ugruk hunting camps up and down the coast where the reindeer fawned. People remained at those camps until the baby deer were old enough to make the migration to summer pasturage at Cape Espenberg. In 1919 the Barr brothers constructed a reindeer corral at the cape. The corral was used for multiple purposes. As the deer were driven through the chutes, each herder’s animals were counted. Additionally, young bulls destined to become steers were moved into a holding pen awaiting castration. Fawns then received the earmarks of their mothers. It was during the summer of 1921 that Gideon’s mother also had a baby at Espenberg—his sister Elizabeth, who became more commonly known as “Bessie.” By the spring of 1922 Thomas had amassed a herd of 1,163 animals.

With the onset of fall, the herders collected the deer and drove them back down the coast to Ublasaun. This cycle was repeated annually until 1925. These were the years of Gideon’s childhood that he recalls most fondly:

Starting December, yah. December, January, February, and those months, if the dogs start barking, us kids, we don’t have to go out—our parents had to look out and see if it’s a bear [polar bear] or dog team coming in, because your dogs will, as soon as they hear something or smell something, then usually they start barking.

Well, I like it [Ublasaun] because it was nice, clean life, happy life. Hardly anybody get to arguing or something and, when something starting to come up that’s not right, they’ll, our fathers, get together and talk it over and advise whoever, whoever try to get off the line. They give them good advice, saying that’s not the way to live. You won’t be living happy…And they won’t care to help you no more pretty soon, because you’ve done something that is not right with all the, all the neighbors. That was the real strong advice. Those old, old people, old women and old men. These women take care of their young girls and those old men, they would take care of the boys. They keep on advising them. [Barr 1991e]

By 1925 the lives of Thomas Barr and his family underwent considerable change. However, to understand the nature of this transformation in the lives of the people of Ublasaun, we must return to the events that preceded the formation of the community.

In approximately 1869, two years after the purchase of Alaska from Russia by the United States, Thomas Makaiqtaq Barr was born at Cape Espenberg to his father Kunautaq and his mother Kuvaaq. As a small boy, Thomas lived at Singiq across the lagoon from Qivaluaq. It is near this location that Thomas’s father was eventually buried.When he was a small boy during the fall and winter, Thomas played at the area of an old village called Ikpiziaq, located about one mile from Singiq on the east side of the Kalik River. By 1937 it looked like no one had lived there because drifting sands had covered the remains of the old sod houses. As a young boy, Thomas was told a story about why that village was abandoned:

Sometimes after Christmas, maybe March, when the sun get high enough, when he [Thomas] was old enough to go out, he [went] away from the sod house where his parents lived, [and went to the old village site]. There was a little lake behind that, ah, behind that little knoll that slowly [was] vanishing towards the west, down this way. And there was a little lake right here, right in front it [the village], and in early fall, they decided to play football, they didn’t know that ice wasn’t thick enough. Well, when the people kicked the ball they’re pretty heavy, and all the village people they get out there on the lake and they break through and they lost most of the population from drowning. [Barr 1991e]

One spring when the days got long and were nice, Thomas was playing around the houses at Singiq and Ikpiziaq. He looked up and saw molting animals that were eating from the ground. It was here that he learned that these animals were caribou feeding on moss and lichens on the top of the hill:

He’d [Thomas] be standing right along side the window watching those animals feeding on top and then he would holler at them, shout at them. And when the caribous heard that noise, the shouting he made, they would lift up their heads and listen and start looking around. That’s how close the animals always had to feed even though they are wild in those days… [Barr 1991e]

However, shortly after Thomas was old enough to accompany the men hunting, the caribou began to disappear from the northwestern Seward Peninsula. At that time, the Iñupiat were using rifles rather than bows and arrows for hunting caribou. Thomas remembered when they corralled them using iñuksuk, or cairns of caribou horns. The disappearance of caribou caused hardship for Thomas’s family, as they relied heavily on the meat for food and on the hides for clothing. After that, they became more dependent on reindeer hides obtained through trade with the Siberians from across Bering Strait.

From the time Thomas was about 14 or 15 years old until his early 40s, whaling vessels and trading ships were commonly seen in the waters of the Bering and Chukchi Seas and Bering Strait. In the spring, the whaling ships anchored at Port Clarence to the south and took on crews of Iñupiat whalers, seamstresses, cooks, and cabin boys. While Thomas was not employed by the whalers or traders, he knew people who were. Some Iñupiat thought that it was the whalers and traders with their abundant firearms that were responsible for driving off the caribou as well as killing many bowhead whales and walruses.

In approximately 1889 when Thomas was nearing the age of 20, he began trading with schooners and Siberians near Cape Espenberg and on the Baldwin Peninsula near the site of the contemporary community of Kotzebue. By then, Thomas already had established trading relationships with a Chukchi partner from East Cape from whom he obtained green tobacco, wolf and wolverine skins. The Siberians traveled to Cape Espenberg after going 55 miles in open water from the Chukotsk Peninsula. There they awaited good weather to travel on to the trade fairs to the north or back to their homes. The Siberians—including men, women, and children—lived at Cape Espenberg in makeshift dwellings constructed by their overturned skinboats.

Thomas did not trade beaver pelts, although they were in great demand by the Siberians, because the Iñupiat of the Kobuk River had an abundance of this species and actively conducted trade with the Siberians at Kotzebue trade fairs. People from Serpentine Hot Springs in the interior of the Seward Peninsula and from the settlement of Selawik also were beaver traders. Before metal was available in the trade network, Thomas was told that people from the head of the Kobuk River exchanged jade and jade tools, knives, and ax bits for coastal products. Thomas also remembered umialiit from both the Alaska and Siberian sides trading whiskey. It was sold in wooden casks to the umialiit, who subsequently traded the beverage in lesser quantities contained in flasks manufactured from ugruk intestines.

Thomas had a rifle that he didn’t like because it kicked too much. However, his Siberian trade partner really wanted the rifle. The partner promised Thomas that on his next trip back, he would bring goods to exchange for the firearm. So Thomas gave his trade partner the weapon, but he never received payment because that was the last time the Siberian came to Alaska.

In 1892 Thomas had heard stories about the arrival of live reindeer at Port Clarence delivered on the umiaqpak, named the Bear. Because of the long-established trade with the Siberians for reindeer pelts, the Iñupiat of the Seward Peninsula saw the coming of live reindeer as both being a new opportunity but also as potentially disrupting their social and economic networks with the people of the Siberian mainland and specialized traders in the Bering Strait region. Within two years, some reindeer had been moved to Cape Prince of Wales, where there were permanent White residents—the missionary teachers William and Ellen Lopp and their family.

Photo by Edward Keithahn, circa 1923, courtesy of Richard Keithahn and National Park Service. (neg .074)

In August 1897, Thomas’s wife-to-be, Emily Kuvaaq Payuraq Kiyutelluk, was born at Shishmaref. Some people at Shishmaref had relatives among the Siberian Natives, including his wife’s kin. Emily’s father, Kiyutelluk, was accidentally shot by his brother, Okshuk, while seal hunting the spring before she was born. Emily’s mother’s name was Mary (Mukluwik). Mukluwik’s brother was Charlie Goodhope or Teyeopuk. Mukluwik subsequently remarried a man named Kiyutuk. Thomas’s children referred to both Kiyutelluk and Charlie Goodhope as “grandfather.”

During the year 1898, before he had turned 30, Thomas observed a most amazing phenomenon. He witnessed several White men, including an officer from the umiaqpak Bear, accompanied by Iñupiat guides, driving hundreds of reindeer across the tundra north to Point Barrow—across the tundra that he visualized as the homeland of the caribou that fascinated him as a boy. While visiting Wales that same year, Thomas was sitting in a qazgi and heard the men tell a story that explained how reindeer came to be:

A young man was once hunting caribou, but without killing them. He merely followed them, appearing every time they tried to escape from him; in that way he tired them.

In the end the animals were so exhausted that they no longer avoided him. Thus, they became accustomed to his voice, and were no longer afraid of him.

At length the young man married, but still followed the caribou, which accumulated and became more and more numerous. The only time he came back to the house he had built was when his clothing was worn out. His wife made new clothes for him, after which he went back to the caribou and kept on following them, so that they might become familiar with him. He was wise in his way of handling them, and as he never made them afraid or chased them, they became almost tame.

Summer and autumn passed, and winter came. But still the young man was with his caribou, which were now multiplying while other herds joined his. Then he moved his tent out to the herd, and thus he became the first caribou herdsman.

The caribou were no longer shy like the wild ones. They were very fond of eating frozen urine, and when they began to eat human urine, their hair became speckled with white.

His wife became pregnant and gave birth to a son, and the son grew up. And when he was old enough to help his father to watch the caribou [sic]. They took turns at it; when the father was with the herd, the son slept and vice versa.

Wolves were numerous in the land where they lived, and they bit the caribou to death. One day the father complained that the son slept too long, which was the reason why the caribou were killed.

The son took this accusation to heart; and so one evening when his father had returned to the herd, the son dressed himself in festive clothing and asked his mother to give him a substantial meal. Later, mother and son retired to rest, but during the night the son thrust a knife into his heart and killed himself—out of anger at his father’s reproach.

Next morning his mother saw the blood on the platform; she lifted the caribou skins and saw her son lying dead. This caused her deep grief, but as she wanted her husband himself to find his son dead, she dried up the blood and covered the body again with the sleeping-skins.That evening the father came home. He inquired after his son and was again angry at his sleeping so long; and when he had eaten the food his wife had prepared, he went to waken him. He flung the skin aside-and found the boy lying dead on the platform. His grief was great, and the mother made it greater, for she cried: “It is your own fault; you killed him yourself with your reproaches!”

Autumn came, and the father traveled to some people living near and urged young men to accompany him; he wanted them to help him kill long-horned caribou bulls.So they killed long-horned caribou bulls, many of them, and the father then had them build two large vaults of caribou antlers laid criss-crossed, and then these were covered with skins; and in one of them the father laid his dead son.

Then he mounted to the top of the other and spoke thus-wise to the young men standing around him: “Let this, the land of the tame caribou become your land; do not sell them and do not kill them off, but let them become more and more. Use them; kill of them what you require in order to live without sorrow and anxiety, but never more than that!”

Having said this, he divided his herd among the young men who had helped him to build the vaults; then he stabbed himself with his knife as his son had done, and was buried in the other vault of caribou antlers.

Thus, says the tale, died the first man to tame caribou; from him descend all the other herds.The two burial chambers are still shown as a monument over the first people to live on tame caribou. [Barr 1991; this story was also told to Knud Rasmussen by Atarnaq of Wales in 1924]

Later in his life, the moral of this story was to be significant in Thomas’s advocation of “close herding.”

In the same year as the reindeer drive, Thomas saw more White people than he thought existed in the world. Gold-seeking prospectors and miners crossed the Seward Peninsula in a wave that was to deluge the Iñupiat. Thomas heard stories of the growth of large White villages south of Wales near Ayasayuk (Cape Nome), and in the vicinity of Point Clarence at a new settlement called “Teller Station.” Thomas was puzzled about what all these changes meant to his and his relatives’ way of life.

In 1899 Thomas and his brother Gilbert built a house at Nuiqtat (“rocking motions”), located about eight miles west of the tip of Cape Espenberg on the Chukchi Sea. The place acquired its name from Iñupiat oral history, which described Cape Espenberg as having once been a floating land mass—similar in nature to the way the world was when it was first created by “Father Raven.”

The following year there were concurrent epidemics of measles and influenza, which took a heavy toll on the Iñupiat of the Seward Peninsula. While the White immigrants to the area appeared relatively unaffected by these illnesses, the Iñupiat succumbed in large numbers. Attempts by traditional healers—shamans or angatkok—to battle the evil spirits causing the sickness were futile.

While the direct effect of these epidemics on Thomas is unknown, he and his brother relocated their houses in 1900 to the old Espenberg site—approximately one mile from the coast up the Espenberg River. It was common practice for Iñupiat to abandon dwellings as the result of the death of a relative in any specific house. In fact, if large numbers of people died in any settlement, it was not unusual for surviving members of the community to relocate the entire village elsewhere.

As a young boy, and later as a grown man, Thomas had seen the cycle of at least two economic “booms” and “busts” in his life mostly undertaken by White immigrants to Alaska. While Thomas had passed through life to this point in an atmosphere of dramatic change, he could not have predicted that there was much more to come, instigated by world markets and players of which he had no knowledge. Although commercial whaling continued into the first decade of the 1900s, the industry had commenced its decline in the early 1860s before Thomas’s birth and, by 1907, was no longer economically viable due to the collapse of the whale oil and baleen markets. About the same time that whalebone (baleen) was no longer of mercantile importance, the trading schooners became a conduit for Iñupiat participation in the arctic fur trade. Fox pelts became a resource of considerable demand.

Photo by Edward Keithahn, circa 1923, courtesy of Richard Keithahn and National Park Service (neg. 217).

In 1898 the western gold rush had expanded into the far north, with the sprouting up of the “boom” mining communities of Deering and Candle in 1901, located a short distance east of Cape Espenberg and Thomas’s and his brothers’ summer homes. Deering and Buckland had a profound influence on the lives of the Barr family in subsequent years.

Stanley Kivyearzruk from Wales had entered the herding program and became an independent herder by 1905. Thomas knew Stanley through his visits to Wales. Early in 1905, Stanley Kivyearzruk’s apprentices, Harry Kigrook and Frank Asunok, built houses that served as reindeer camps about halfway between the tip of Espenberg and the mouth of the Goodhope River. Harry Kigrook was the father of Fannie Kigrook—who later became Gideon’s second wife. The formation of this herd adjacent to Cape Espenberg piqued Thomas’s interest in acquiring his own deer.

By 1905, Thomas and his brothers were too mature, and more importantly, too well established in life with large kin followings and investment capital to have reduced their status to that of mere reindeer apprentices with no guarantee of reward at the end of a period of indentureship. At this time deer became more readily available to those Iñupiat who were capable of purchasing them without serving the mandatory apprenticeships. Thomas purchased his initial five reindeer from James Keok of Wales on August 14, 1905, for five fox skins and $100 in cash.On July 27, 1907, Thomas bought 13 more deer in two separate purchases from James Cross, who was superintendent of the Wales Congregational Mission. Thomas’s brother Gilbert also purchased reindeer, bringing the total of their combined herd to approximately 100 animals. Though the bill of sale designated these deer as going to Deering, they were located on the range next to Cape Espenberg and to the south as far as the Lane River range used by Stanley Kivyearzruk. Those deer were purchased for the Barr brothers—Thomas, Ahvalook, and Gilbert. Soon other people in the Espenberg area obtained deer, including Thomas’s youngest brother Peter, who had served as an apprentice for William Ookonok and had been adopted out of the Barr family as a child; Harry Kigrook; James Kivetoruk Moses; and Adrian and Walter Barr, Ahvalook’s sons.

Between 1905 and 1910, Thomas experienced some major events that altered his status and role in his social network. His eldest brother Ahvalook died, leaving Thomas as the oldest male in the sibling group responsible for the other brothers and their families and Ahvalook’s adolescent sons. In that period Thomas also wed Emily—a young woman half his age, stepdaughter of Kiyutuk, and the maternal niece of aspiring reindeer herder Charlie Goodhope. Neither the age difference nor what appears to be an arranged marriage was atypical of the Iñupiat of Northwest Alaska at that time. Shortly thereafter, Thomas began raising a family. Lastly, during these years, Thomas and his brothers were involved in both “traditional” and more contemporary economic activities, including reindeer herding, trapping, hunting, fishing, trading, and seasonal wage employment in the mines near Deering.

Photo by Edward Keithahn, circa 1923, courtesy of Richard Keithahn and National Park Service (neg. 080).

Photo by Edward Keithahn, circ 1923, courtasy of Richard Keithahn and National Park Service (neg. 211)

Between 1909 and 1918 Thomas used Qivaluaq, his childhood home, as a headquarters for winter herding activities with James Keok from Wales, chief herder of what was referred to as the Shishmaref Number 2 Herd. Thomas, his brothers Gilbert and Peter, and their apprentice Gordon Dimmick had a total of nearly 100 deer in this herd. Besides Keok and the Barr brothers, other men owning animals in the herd included H. Karmun, T. Kotenna, A. Kiyutelluk, D. Iokwana, H. Kokizowak, Outpolluk, Soagzrunuk, Nealotok, Pete Ehechvaiuk, Charlie Goodhope, Ahinkok, and W. Okouok. The Shishmaref No. 2 herd was bounded on the southeast by the Buckland River animals herded by Thomas Sokwenna. Stanley Kivyearzruk’s herd at the Goodhope River was also located to the southeast. At that time, two Kotzebue herds were to the northeast on the Baldwin Peninsula, the first of which was principally owned by the Friends Mission and the second largely belonging to Sami herder Alfred Nilima. Two other Shishmaref herds were to the south and southwest, the first composed mainly of deer belonging to John Sinnok with some government animals, and the second ranging at the Serpentine River, principally owned by Allockeok.

Lloyd Koonuk’s brother Allockeok had become a powerful reindeer entrepreneur. As a young boy, Allockeok was adopted by a White man named Thomas Chase, a miner at Kougarok. As a result of growing up with a White father, Allockeok was a fluent speaker of English. He referred to Gideon as “nephew.”

During the years Thomas and his family lived at Qivaluaq, their square house was constructed out of materials salvaged from a shipwreck. Ralph Olanna’s parents owned Thomas’s home and lived next door. During those years, Thomas and his brothers built an umiaq at Cape Espenberg, and Thomas and Emily had three girls—Fannie, Martha, and Suzy. The Barr brothers and their families wintered here and hunted in the area from Qivaluaq to Cape Espenberg and inland to Serpentine Hot Springs.

Edward Keithahn, circa 1923, courtesy of Richards Keithahn and National Park Service (neg. 079).

In 1914 Thomas knew many Iñupiat who had been living in the mining camp at Deering where a school had been established. All the Iñupiat of the area were told by the Friends missionary/teachers that Deering was an “evil” place where non-Natives were “corrupting” the local Eskimos. That year the missionaries relocated the school and most of their Iñupiat followers from Deering to a site on the Kobuk River named “Noorvik.” To Thomas, it was puzzling that the missionaries and the White “God” had so little influence over the miners. It also appeared to Thomas, his relatives, and friends that White laws, enforced by the umialiqpuk (“big boat captain”) of the revenue cutter Bear, were used to punish the Iñupiat, but not the White miners, whom the missionary/teachers thought were so bad.

The following winter, Thomas went to the first reindeer fair held at Igloo in the interior of the Seward Peninsula. Reindeer herders came from far and wide for this gathering. It was at the fair that Thomas met the White businessmen from Nome, the Lomens. The Lomen family recently had purchased Alfred Nilima’s deer that had been in the Kotzebue herd and now were located on the Seward Peninsula in the vicinity of Buckland. In addition to the Lomens, there were many other White men at the fair including Walter Shields, the reindeer superintendent for the northern district, and T.L. Brevig, the missionary from Teller. Some of the White people were telling Thomas and the other Iñupiat herders that there wasn’t enough range for the large number of deer. Therefore, the Iñupiat herders were encouraged to form village companies or associations, putting all their deer under one mark and hiring a chief and assistant herders. Although Thomas and the other herders enjoyed the driving, lassoing, racing, and other contests at the fair, he didn’t think that the formation of a company was a good idea.

In 1917 Thomas and Emily had their first son whom they named Gideon Kahlook Kunautaq Barr. World War I had already begun in Europe, and Thomas and his brothers, having acquired a suitable number of reindeer, were preparing to move their winter camp to Ublasaun where they remained for several years as individual deer owners with a common herd. The winters were spent at Ublasaun and the summers at Cape Espenberg.

In 1925 the reindeer industry was in a state of disarray, thereby disrupting the lives of Thomas and the other residents of Ublasaun. While Thomas and his followers had amassed a considerable number of reindeer, there were very few outlets for either deer meat or hides. The Lomens’ company was dominating the market outside Alaska, and Whites located in mining camps still operative, such as at Deering, were supplied by the nearest herders. Meanwhile, the federal government, through its superintendents, adamantly continued to discourage Iñupiat herders from killing their deer for their own consumption. Thomas was aware that some herders had opted to adopt open herding over the more cautious and, in many Iñupiats’ opinion, more responsible methods of close herding they had been taught by the Whites and Samis in the past. Some herds were officially consolidated into companies, while others were becoming unavoidably mixed. In some respects, the deer had gone from being an asset to becoming a liability.

The settlement at Ublasaun was disbanding. Peter Bart, Lloyd Koonuk, and Gordon Dimmick began spending most winters at Shishmaref. Gilbert Barr also maintained a house at Shishmaref which was 12 feet by 16 feet, and was occupied by him and his family of seven for part of each year. However, Gilbert continued to take his deer to Cape Espenberg in the summers and eventually moved to Deering for the winters. By the end of the summer of 1925, Thomas’s and his brothers’ deer had become mixed with the herd of Stanley Kivyearzruk.

In the two years to follow, Thomas and his family were to make several important moves. Ublasaun was abandoned as a winter herding settlement. By 1926, approximately at the time of the death of Thomas’s sister who had been living with them, the rest of the Barr family—Thomas, Emily, Fannie, Gideon, Elijah, Bessie, and Mary—officially moved from Ublasaun to Deering, in part so that the children could go to school. Elijah died at Deering of a ruptured appendix during the winter of 1926, and his sister Fannie died in the hospital at Kotzebue the following April. With the death of Fannie, Gideon became the eldest of the Barr children.

Gideon and his sister Bessie attended school. In 1990 Gideon recalled going to school in Deering:

"I didn’t walk into school until I was nine years old, ‘cause my father had to stay out in the country [with the reindeer]. I used to be ashamed of myself so much. I’d be real tall boy compared to those little primary kids, that’s the worse thing that I could ever stand, because for me being tall and the rest I went to school with, they’re so small. It’s really painful, [I] was ashamed of myself. It wasn’t my fault." [Barr 1990]

While at Deering in the winters and at Cape Espenberg in the summers, Thomas and Emily had more children, including the twins Nora and Mabel and another daughter in 1929, whom they named after the deceased Fannie. In 1930 Laura was born and in 1932 they had another son who they named Elijah after the son Thomas and Emily had lost in 1927. Finally, the youngest child Bill (or Zaccheus) was born in 1935.

Since the original school in Deering had been dismantled and moved to Noorvik in 1914, the new teacher Clarence Andrews, who had arrived in Deering in 1925, renovated a saloon to serve the purposes of a facility for educating the 38 Native children of the town; white children attended a different school. Most of Deering’s 75 people were Iñupiat. While Deering had become somewhat less of a roaring frontier town by 1926, it had retained the flavor of an early twentieth century mining community with a roadhouse that served as a saloon and dance hall. Since many of the White miners had already abandoned the Seward Peninsula, Iñupiat men were seasonally employed in mining, mostly handling the hydraulic nozzles that cut away at the tundra to expose the gold bearing soils beneath. Iñupiat women were busy catching and processing salmon for their families’ use. Most of the Iñupiat were living in one room frame cabins abandoned by White prospectors and miners. For example, Gilbert and his family—he and his wife, seven children, and his wife’s father and mother—resided in a one room frame cabin with a loft.

The second move took place at the Barr’s summer camp at Cape Espenberg in 1927. The family moved from old Espenberg to a new house located about one mile from the mouth of the Espenberg River. As recalled by Gideon in 1984, although the family was wintering in Deering, Espenberg remained their home from early May, throughout the summer, and until the first part of September when school started. Gideon recalled:

"Mostly I was raised out in the country around Cape Espenberg area where there is hardly any people. There is some people, but, not a village. It’s just the family people that took care of the reindeer herd mostly." [Barr 1984a]

At the new site at Cape Espenberg, Gilbert and his family lived next door to Thomas’s family. Moses Quiliq and his adopted son James lived five or six miles away on the west side of the Espenberg River, as did Thomas’s eldest, deceased brother’s (Ahvalook’s) three sons, Arthur, Adrian, and Walter. While the children were growing up, Emily’s stepfather and mother lived with them. Thomas’s parents had died long before.

In 1927 the government succeeded in changing the reindeer program from individual owners and ear marks to cooperative herds. The Iñupiat owners of the Lane River (Stanley Kivyearzruk) and the Espenberg herds formally organized into a company on July 17, 1929, which they decided to call the Nuglunguktuk (also recorded as Nuglinuktuk, Nuglunuktuk, Niqlanaqtuuq, Nugnugaluktuk, Niglinuktuk, Neglunuktuk, Neglinuktuk, Nugglugnuktuk) Reindeer Company named for the river that drained the range. The Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company had its roots in a less formally organized Cape Espenberg reindeer cooperative established in 1927 in association with the shift in government policy and, more practically, the mixing of animals from the two herds. Since there was no school at Cape Espenberg and no teacher to act as local reindeer superintendent, Deering became the headquarters for the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company. The deer owners from the area, including Thomas, explicitly did not want to join with the Shishmaref herd. Although some owners previously had signed to be part of the Shishmaref herd at the request of government officials, they had changed their collective minds and returned to Cape Espenberg.

Thomas and the other herders agreed that the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company was to have a five-member board of directors, four of whom were to be elected by stockholders and the sixth being the local representative of the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs. At that time, the reindeer superintendent was teacher Clarence Andrews. Thomas was elected president of the company at its first meeting. Stanley Kivyearzruk became vice-president, Harry Kigrook the secretary, and Thomas’s paternal nephew Adrian the chief herder.

The Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company applied for a grazing permit to include the lands previously occupied by the Lane River or Stanley Kivyearzruk herd and those pasturages used by Thomas Barr and his brothers. The combined range was situated between that of several other reindeer companies. The Deering Reindeer Company’s range was to the east, while those of the Seward Peninsula, including the Shishmaref herd,were to the south and west. The Igloo herd lay to the south, whose range in 1929 was described by Thomas and recorded by teacher Andrews as follows:

"The boundaries of their [Nuglunguktuk Company] combined range are as follows: Beginning at Cape Espenberg, where the waters of the Kotzebue Sound join the Arctic Ocean, the east boundary is the shoreline of Kotzebue Sound as far as to the mouth of the Goodhope River, thence up the Goodhope River to the mouth of Humboldt Creek, thence up Humboldt Creek to its head. The boundary from that point turns northward and follows the divide, or watershed, between the waters that flow into Kotzebue Sound to the mountain 1,000 foot high at the head of the Serpentine River, thence north on the ridge to Devil Mt., thence north to head of Ikpoogrook River. Thence down that river to the Arctic Ocean. Thence east to Cape Espenberg. This would bring it back to the point of beginning, at Cape Espenberg. They have occupied a small amount of territory on the Arctic shore and have a corral at the mouth of the Nunagayok River, which flows into the Arctic about 8 or 9 miles west of Cape Espenberg. This brings a part of their range into the Seward Peninsula District. The far greater part, however, lies in the Northwestern District, according to the description given in the orders concerning the lines of the districts as divided. To split on the watershed is difficult as it makes a long, thin strip of land on each side of a divide which is poorly marked as it is a very flat country full of marshes and small lakes." [USBOE 1923-1944]

Between 1929 and the early 1930s, there were consequential range disputes between the Shishmaref Reindeer Association, the Deering Reindeer Company, and the Nuglunguktuk Company, and William Allockeok and his brother Lloyd Koonuk, who had become partners after the dissolution of Ublasaun. In his capacity as president of the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company, the then 60 year-old Thomas enlisted the aid of his children’s teacher Clarence Andrews in trying to protect the range of the herd.

Of the numerous range disputes, the one between Thomas’s company and that belonging to Allockeok and Koonuk was the most troubling, and involved a barrage of letters and telegrams between Andrews, on behalf of the Nuglunguktuk Company, and other local and regional reindeer superintendents and reindeer companies competing for good range. In justifying their claims to the disputed territory, Allockeok and Koonuk had drawn upon the fact that the latter had been living with Thomas at Ublasaun between 1918 and 1925. Additionally, although Allockeok and Koonuk were brothers, the latter’s second marriage had been to a woman whom Thomas considered to be his sister’s daughter. Furthermore, Thomas’s son Gideon remembers that his father and Allockeok considered one another kin.

Clarence Andrews was a strong proponent of close herding. In his capacity as superintendent charged with oversight of the reindeer of the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company, he told Thomas how bad open herding was. Andrews convinced Thomas that the government was promoting open herding only to benefit White owners such as the Lomens. In addition to the range wars, Thomas, as president of the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company, was confronted with a shortage of adult men capable of participating in the herding operation, since the roundup activities conflicted with other forms of employment.

During the depression commencing in 1929, Thomas was to experience another event in world economics over which he had no control and about which he had little direct understanding. The prices for fur pelts and reindeer fell dramatically, while the value of gold actually increased. The placer mining operations on the Seward Peninsula once again boomed. Therefore, many herders found that their most successful avenue to obtaining Western goods was by being employed at the mines in Deering and Candle.

During the depression, when Thomas’s son Gideon barely had started the fourth grade, his father took him out of school on November 10, 1930. In 1990 Gideon poignantly recollected this event:

" Just when I was really get into it, you know, school, when I was 13 years in the fall. So I didn’t even know he [Thomas] walked in, because we were facing away from the door. And someone came along and touched me on my shoulder. I looked up, it was my father. I asked him “what”? He said, “Son, you won’t become a teacher. Now I already talked to the teacher here. Now you have to go home with me. I’ll show you how to hunt. You won’t become a teacher no matter how much schooling you try to get. But if you, if you learn how to take care of yourself the real Eskimo way, the subsistence way of hunting, you won’t go hungry. You’ll be safe to live up here in Alaska.” These things were more important than school to him [Thomas], because that was the only way. Well, got to be a good hunter, then you’ll never go hungry. If you’re lazy or not a very good hunter, then your family, if you have a family, they’ll go hungry anyhow. That was the purpose that he [Thomas] was looking after." [Barr 1990]

So Thomas taught Gideon to hunt. Thomas showed Gideon how to set traps, go after foxes, hunt seals, and use kayaks in the spring. Father and son also got ugruk on top of the ice in the spring and learned to put a little air under the skin of a seal in water, plugging it so that it floated.

Thomas also took Bessie, his second oldest child, out of school in 1930 when she was nine years old. Thomas taught her how to hunt and drive dogs as well, as he was disappointed in this time of need that she was not a son. According to Bessie, he raised her to be a boy. By the time Bessie was 10 years old, she had her own dog team. When her team had pups, Thomas told her that he could not allow her to feed them reindeer meat. If Bessie wanted to keep them, she would have to feed them some other way. So, unaccompanied, Bessie took a boat to a nearby island, where she knew seals sunned themselves in the spring. There she shot four spotted seals to feed her pups. When Bessie was between 10 and 11 years old, she used her dog team to ferry supplies between the Barr home on the coast at Cape Espenberg and her father’s, paternal uncles’, and their sons’ trapping cabins in the interior of the Seward Peninsula.

In 1930 Thomas had few options but to take his two older children out of school to help support the family. He was now over 60 and, given the economic failure of the fur industry and his inability to convert reindeer into cash, subsistence from the land and sea became the only viable means of supporting his family. After taking Gideon and Bessie out of school, Thomas moved the family to Buckland for nine months, returning to Deering and Cape Espenberg in the summer. During this year Emily’s stepfather, who had been living with them, died before completing a bow he was making for Gideon. Once Gideon and Bessie were helping support the family, Thomas and Emily remained in Deering most of the year so that the younger children could attend school.

By 1931 Thomas held 22.4 shares in the Deering Reindeer Company, which, by 1932, had grown to a total of 15,863 animals. At the same time, Thomas personally owned 48 deer and 460.2 shares in the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company. Thomas and his brothers and their collective offspring together owned the majority of deer (1,014) in the Nuglunguktuk Company. By then, Harry Kigrook was the secretary of the Nuglunguktuk Company.

In 1931, Thomas had to deal with another major dispute between the Shishmaref and Nuglunguktuk companies. Despite his objections, the local reindeer superintendent at Deering, named Moyer, ordered the Nuglunguktuk herders to remark 725 Shishmaref reindeer corralled with their own herd as belonging to the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company. Moyer assured Thomas and the other herders that there would not be a problem, as he was sending a letter to the reindeer superintendent at Shishmaref instructing him to remark the same number of Nuglunguktuk deer expected to be corralled with the Shishmaref herd to their company. Moyer explained that this solution was better than the alternative of driving deer between the two herds. The problem was that there were not 725 deer from the Nuglunguktuk company herd corralled at Shishmaref in that and subsequent years. Consequently, Moyer realized that the deer were not moving between the Shishmaref and Nuglunguktuk herds, but, rather, that the Shishmaref Reindeer Company and Allockeok had invaded the northern range. Thomas perceived the mixing of the herds to be a direct result of the open herding policy being promoted by the federal government.

In the early 1930s, wolves that ostensibly had moved south and wiped out the Noatak and Kivalina herds came onto the Seward Peninsula and began killing reindeer. In 1982, Gideon Barr recounted the events of the period and echoed his father’s sentiments about the evils of open herding:

" Finally all the company earmarks was all mixed up, cause, the herd was all mixed up. Summer time, they just turn them loose…And they got too many and they overgraze the Seward Peninsula…And then [1927] they starved out, and then the wolves come in from the north. That’s the way the reindeer was unlucky. Government, government got hold of a little herd from Deering and then put it up at Selawik. And this guy that saved that government herd was name Charlie Smith from Selawik. When wolf come in from up north, so he took care of that herd, night and day, winter and summer, and that’s how come there was a little herd left. And then when the wolf go away and then that herd, ah increase rapidly and then they start to roam out some. Little herd, here and there. Now it’s all back to Seward Peninsula again… [In] 1927, that’s when they let the herd go. Nobody, nobody really take care of the herd of their own. They just turn them loose." [Barr 1982]

For Thomas, the wolves killing the deer was clearly the result of herders “sleeping too much” and not paying adequate attention to their animals, as was foretold in the story he had heard at Wales as a young man.

By 1932, the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company was facing many problems. In late July and early August of that year, a roundup of deer at the company corral indicated that Nuglunguktuk had a mere 1,915 deer, a decline from the 6,000 animals in the herd the previous year. These included mavericks marked to the company, fawns killed for parka skins, individual owner marks transferred to the company, and deer from the Cape Prince of Wales herd. Additionally, Deering teacher William Fortson reported that the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company had no “finances whatever and the individuals have had a poor income for the last year and are in no position to build a new corral.” As a result of the depression, employment in the gold mines at Deering and Candle was the only viable means by which Iñupiat of the area could obtain cash.

Reindeer herding suffered in two ways. Since men were employed in mining, there were few available for summer roundup activities. Secondly, because furbearer trapping was no longer lucrative, Thomas and his peers were incapable of supporting themselves through trapping in conjunction with herding during the winter months. Wages associated with employment in the mines were not matched by the reindeer industry, and herders were unable to convert deer into currency. As a result, adolescent boys and some girls and women attempted to undertake summer roundups for purposes of marking, castrating, and butchering reindeer, but with marginal success.

In 1935, reaching the age of 15 when young men were expected to become more self sufficient, Thomas’s oldest son, Gideon, stopped living in his parents’ home and took up residence with his father’s brother’s son Walter Barr, who was 28. They lived in a cabin at Killeak lakes.

In 1937, Walter married Grace Tipplemen from Candle, and they resided in the cabin after their marriage. Grace already had one daughter, and she and Walter had five more children—a daughter in 1942, a son in 1943, and three other daughters in 1945, 1946, and 1948. Grace died in 1948.

The year Walter and Grace married, Gideon, the bachelor, constructed a trapping and herding cabin at the headwaters of the Nugnugaluktuk (also recorded as Nunagaluqtuq or Nugnugalurtuk) River. Gideon was now indisputably an adult Iñupiaq living on his own.

The year 1937 was to be important in the life of Thomas, Emily, and other members of the Barr family. By then, Emily’s mother had died. Most of Thomas’s family, including Gideon, had moved to Singiq, where the former had lived as a young boy and grown up. There were three or four homes at the Singiq settlement. The area was an excellent location for winter and spring fish camps, as whitefish were available year round and were netted in the water under the ice. Here Gideon built a home for his parents Emily and Thomas, who was then 68 years old, and his mother Emily, next to James Moses’ house. James and his wife Bessie were operating a small store at Singiq for White fur buyer John Backland—the son of the captain of the four-masted trading schooner Thomas had seen as a young man. During this same year, Gideon also constructed a plank-walled house for his own use on his 139-acre allotment and ran his trap lines up and down the coast and some distance inland. Unfortunately, a fall storm in 1937 pushed the waters of Kuukpaum Imagrua (known also as Cowpack Inlet) onto the beach, thereby destroying the Barr family’s 30-foot wooden whale boat that had been stored there—a loss worth more than $1,000 at the time.

In the fall of 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Reindeer Act—a piece of legislation that was to affect the future history of the reindeer industry throughout Alaska by limiting ownership of reindeer to Natives. With the government’s acquisition of the Lomen deer and the removal of non-Native competitors, Thomas again had hopes that he or members of his family could benefit from the endeavor he had begun in 1905 with the purchase of his first reindeer. By this time, Thomas was too old to personally undertake the rigors associated with herding. Yet, he still hoped that his eldest son Gideon, who was still actively engaged in herding as secretary of the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company, would further the family’s position in the herding business. Using a traditional Iñupiat means of forming alliances with other families to achieve economic gain and prestige and to resolve disputes, Thomas and Emily arranged a marriage between their son Gideon and Katherine Eningowuk, the daughter of Joseph Eningowuk. In 1923, when Thomas and the others were at Ublasaun, Joseph Eningowuk had been a large owner and the chief herder of one of the Shishmaref herds. In fact, that year Joseph owned 284 of the total 905 deer in this herd, with four other herders having nearly 100 deer each. In 1984 Gideon described this marriage as follows:

"Someone has talked—has planned us. That’s the way it turned out to be. I guess I wasn’t really for it at first, and at first she wasn’t really my choice. But we just have to listen to the older people." [Barr 1984]

Gideon and Katherine had a stillborn son the following year.

After the passage of the Reindeer Act, the federal government continued to attempt to control the Iñupiat in all aspects of herding. For example, government officials wrote frequent circular letters to “Eskimo” owners encouraging or, more appropriately, ordering them to carry out the earlier policy of maintaining close and constant herding, construct more corrals and cabins, kill wolves, conduct more thorough roundups, and divert the profits from the sale of reindeer into the management of the company as opposed to the benefit of the shareholders.

Thomas’s revived hopes for his family’s success in the reindeer industry were dealt a severe blow during the harsh winter of 1938 to 1939, when as many as half of the reindeer throughout Alaska perished. During that winter, Gideon and his wife Katherine lived in Shishmaref, while Thomas and Emily remained at Singiq. In 1939 the administration of the Nuglunguktuk herd was transferred from Deering to Shishmaref because most of the active members of the company were residing the greater part of each year at Cape Espenberg or Shishmaref rather than at Deering.

In 1940 the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company was not doing well. Thomas owned only 30 deer valued at $100. Harry Kigrook was the president of the company, while Gideon acted as secretary. The Deering cooperative lost many deer that year, as the dispute between the Nuglunguktuk and Shishmaref reindeer companies concerning the handling in 1931 was resolved. Nine years after the conflict started, the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company was pressured to provide the Shishmaref Reindeer Company with 725 deer to compensate for the marking fiasco of 1931. The same year Thomas and Emily, and Gideon and Katherine moved back to Deering from Singiq and Shishmaref, respectively. Thomas still had six children living at home. Shortly thereafter, in 1941, Thomas’s first living grandchild Christina was born to Gideon and Katherine. Gideon resigned as secretary of the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company, being replaced by his paternal cousin Adrian Barr.

In 1942, Thomas was 73 years old. His hopes for his family’s future in reindeer herding seemed doubtful as had those of some of his relatives and competitors, such as Lloyd Koonuk and William Allockeok. Gideon’s involvement in the company had ended, and he began working at the mine in Candle. Adrian, who had been the chief herder of the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company, sold his house at Espenberg and moved to Teller with his wife Louise and their children.

In the same year, Sam S. Kendrick, Bering Unit Manager of the Alaska Reindeer Service at Teller, wrote a letter to J. Sidney Rood regarding, among other things, the “poor” condition of the Espenberg herd. He stated:

"The Nuglunguktuk is very inactive at present, because about 90 percent of the owners live at Deering and Kotzebue, the balance at Shishmaref. I have been using my influence to dissolve this organization and hope to get better results this year."

Kendrick wanted to combine Allockeok’s herd with that of Shishmaref. His goal was to dissolve the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company and turn over the range to the Shishmaref enterprise. Although not official until 1948, the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company was no longer considered a functional herding concern. Sam Kendrick’s recommendations were ultimately successful.

By World War II, reindeer had become a basically negligible component of the economy of the area. People were living much as they had 36 years before when Thomas has purchased his first reindeer. As noted by a Shishmaref teacher, ugruk was the primary food source for the residents of the northern Seward Peninsula. In one year local Iñupiat consumed 13,200 pounds of ugruk, most of which was dried and stored in seal oil and poke containers. Herring was the second most important resource in terms of weight at 11,000 pounds. The teachers reported that no Iñupiat was interested in gardening, and there was no mention of reindeer as a food resource. The government teacher at Shishmaref had the following observation:

"I have watched the natives for five years, and I find that there is nothing that will keep them away from taking their foods at the proper time. It appears to me at times that they do not work at their jobs enough, and I often hear others state that the natives do not work at gathering a supply of native foods enough, but I then wonder what I and those that criticize would do if we were in the natives’ place. I saw one of my natives go out on the Arctic ice this past spring for the tenth time before he got his first oogruk [sic] of the season." [USBOE 1923-1944]

In 1991 Gideon recalled his and his father’s last trip to Ublasaun:

"In the early 1940s, we stayed about maybe one month and a half or so. My father wanted to stay here…The house was in good shape then, ‘cause just before freezeup [we had repaired] the roof. We were still up at Espenberg area, and right after freezeup then [Thomas] he took us down here." [Barr 1991e]

In 1942, in response to World War II, Gideon moved without his family to Nome to work as a warehouseman for a construction company under contract to the U.S. Army. Katherine, their daughter Christina, and son Delano born in 1943, remained in Deering with Thomas, Emily, and other members of the family.

In the fall of 1944 Gideon received word that 75 year-old Thomas was ill, so he returned to Deering from Nome. Thomas knew that he was dying, and asked Gideon to obtain some fawn reindeer meat—his favorite food. Gideon and his paternal cousin, Walter, left for Cape Espenberg to get the fawn meat for Thomas. While there, the weather became bad and they were stormbound for one week. Upon their return, they learned that Thomas had died.

Ublasaun was no longer used for either reindeer herding or as a seal hunting and fishing camp by Thomas’s brothers, sons, and nephews. With Thomas’s death, and the demise of the Nuglunguktuk Reindeer Company, the hope and promise of Ublasaun were gone. The following summer, baby boy Thomas Makaiqtaq Barr was born to Gideon and Katherine.

Listen to oral histories from past and present reindeer herders in the region on Project Jukebox.