Last updated: October 4, 2020

Article

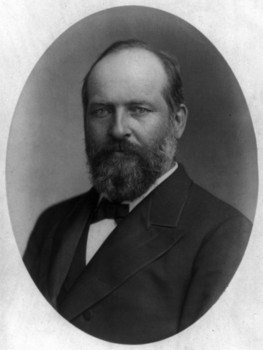

The Front Porch Campaign of 1880

Library of Congress

The 1880 “surprise” presidential nomination of Ohioan James A. Garfield by the Republicans resulted in a campaign that, unlike any before it, regularly brought citizens and candidate face-to-face. It was conducted on the front porch of Garfield’s home.

Prior to 1880, it was considered undignified for anyone to actively seek the presidency. Nominees did not travel from state to state or city to city to tell voters that they had the solutions for the country’s problems. Expected to emulate the example of George Washington, they were to remain above the fray. The sitting president, Rutherford B. Hayes, spoke to this tradition when he advised Garfield to “sit cross-legged and look wise until after the election.”

Traditionally, it was the Congressmen, Senators, and party workers who did the heavy lifting during presidential campaigns. It was they who traveled, they who spoke, they who organized evening torchlight parades, and more. Garfield honored these traditions. Meanwhile, he stayed home; he stayed put. But his 1880 campaign departed significantly from past practice.

NPS

Arriving at his Mentor farm after his nomination at Chicago, Garfield was greeted by crowds of citizens. People who had known him from his days as a student, teacher, and Civil War officer came to wish him success. Newspaper reporters camped out on his lawn. Their accounts of the welcome Garfield received stimulated interest in his candidacy.

Farmers and businessmen, college students and women (unable cast ballots in 1880), immigrants and Union veterans, including a number of black veterans, came to see, came to hear, and came to meet the Republican nominee.

In the little campaign office behind his home, Garfield and his aides exchanged letters and telegrams with the leaders of groups to fix dates and times of arrival, and to exchange information, so that when they met, a group’s spokesman and Garfield could address each other with appropriate remarks.

NPS

An estimated 15,000 to 17,000 citizens traveled to Mentor, Ohio (population: 540) to see and hear Garfield. From a train platform specially built to bring the people to the candidate, they literally walked a mile-and-a-half up a lane that extended the entire length of Garfield’s 160 acre farm. They walked up that lane in good weather and in bad, in sunshine and in showers.

Often, a “Garfield and Arthur” band was playing near the front porch when visitors arrived, adding excitement to the air. Poets read and singers sang. A Congressman, Senator, or local official would hail the Republican Party and Garfield.

Soon, the candidate would pass through the vestibule doors leading from the interior of his home to his porch. A designated group leader addressed him respectfully. Garfield would respond, eschewing political issues. He spoke instead to the identities and the aspirations of those gathered before him. His remarks were often brief, sometimes lasting no more than three or four minutes. From the porch serving as his podium, Garfield discussed “The Possibilities of Life,” “The Immortality of Ideas,” and “German Citizens.”

As a teacher, soldier, Congressman, and Republican presidential nominee, James Garfield wrestled with the matter of race. It was as difficult an issue for his generation as it is for ours. Still, he supported the right of African-Americans to be free, to be equal with whites in the eyes of the law, and to be treated with justice. In his remarks on “The Future of Colored Men,” Garfield spoke to 250 such citizens assembled on his lawn in October 1880.

Western Reserve Historical Society

“Of all the problems that any nation ever confronted,” he said, “none was ever more difficult than that of settling the great race question… on the basis of broad justice and equal rights to all. It was a tremendous trial of the faith of the American people, a tremendous trial of the strength of our institutions…” that they had survived a brutal and bloody civil war; that freedom had been won for the enslaved as a result; that the promise of fair treatment was to be the inheritance of the freedmen.

When, late in the campaign, he stood before his “Friends and Neighbors” from Portage County, Ohio, he revealed the tender side of his nature, and his appreciation for the life he’d been given. To this audience, composed of the many who had helped to form the fabric of his being, he offered these thoughts:

“Here are the school-fellows of twenty-eight years ago.

Here are men and women who were my pupils twenty-

five years ago… I see others who were soldiers in the

old regiment which I had the honor to command… How

can I forget all these things, and all that has followed?

How can I forget…the people of Portage County, when

I see men and women from all its townships standing at

my door? I cannot forget these things while life and

consciousness remain. The freshness of youth, the very

springtide of life… all was with you, and of you, my

neighbors, my friends, my cherished comrades… You

are here, so close to my heart… whatever may befall me

hereafter…”

And then, as he had so often done before, James Garfield invited his guests to linger in friendly communion: “Ladies and gentlemen, all the doors of my house are open to you. The hand of every member of my family is outstretched to you. Our hearts greet you, and we ask you to come in.”

-Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site

(Park Ranger Alan Gephardt wrote this article in January 2016 for the blog of PBS’s American Experience to coincide with the February 2 national broadcast of Murder of a President, their excellent documentary about President Garfield and his tragic 1881 assassination.)