Last updated: October 25, 2020

Article

The First Lady and the Queen: Two Women Brought Together by Tragedy

Western Reserve Historical Society

In the 1880s two notable women shared a bond that resulted from personal tragedy. One was a Head of State, Queen Victoria of Great Britain; the other was the wife of the Head of State, the American First Lady, Lucretia Garfield. On the surface, their lives did not suggest that the two women had much in common, but a closer look at their early married lives and later actions as widows demonstrates that similar conditions produced similar responses to their roles as the spouses of notable men.

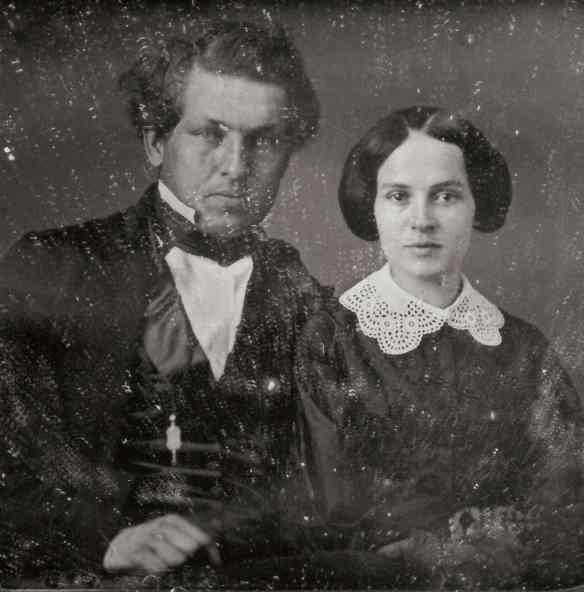

Lucretia Rudolph met James A. Garfield at the Geauga Seminary in Chesterland, Ohio. The friendship which began there blossomed into a courtship at the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (now Hiram College). A long engagement, and then marriage, followed. Both were 26 years old when they married in the home of Lucretia’s parents in Hiram on November 11, 1858. The first years of the Garfield marriage were difficult due to long separations; Lucretia later referred to these as “the dark years.” Garfield served in the Union army during the Civil War and was stricken more than once with illness; at one point he came home to recuperate. It was during this recovery in Ohio that their relationship finally began to improve and strengthen. In these early years of marriage, Lucretia bore first a girl, Eliza Arabella, and then a son, Harry. The death of “Little Trot,” and the birth of “the boy” drew Lucretia and her husband closer together.

Wikepedia

Likewise, some uncertainty plagued the heart of the young British Queen. Victoria was just 18 in June 1837 when she ascended to the throne of the United Kingdom. It was expected that Victoria would marry and produce an heir to the throne. The family hoped that she would marry her German-born cousin, Albert, Prince of Saxe-Coburg. Initially, Victoria did not want to marry Albert, but her feelings changed over time, and she confessed in her diary: “Oh, when I look in those lovely, lovely blue eyes, I feel they are those of an angel.” They married on February 10, 1840.

James and Lucretia had seven children; Victoria and Albert, nine. All of the children of Victoria and Albert lived into adulthood; five of the Garfield children did. However, all of these surviving children lived to see the early death of their father.

Prince Albert’s untimely death took place on December 14, 1861. He was just 42. He had long suffered from ill health. The exact cause of his death has been variously ascribed to typhoid fever or kidney failure. The Queen and five of their nine children were at Prince Albert’s bedside when he died. By the time of his death, Albert had become an indispensable support to the Queen. His death sent her into a deep mourning that lasted the rest of her life. Public grief resulted in the construction of many memorials to Albert, most notably Royal Albert Hall.

National Park Service

The death of President Garfield in 1881 moved the Queen, who never ceased mourning the loss of her own husband. On September 25, 1881, the day before President Garfield’s massive funeral in Cleveland, Queen Victoria wrote a letter to Lucretia Garfield. “I have anxiously watched,” she wrote, “the long, and fear at times, painful sufferings of your valiant husband and shared in the fluctuations between hope and fear, the former of which decreased about two months ago, and greatly to preponderate over the latter- and above all I fell in deeply for you!” As a gesture of her deep sorrow for Mrs. Garfield and the people of the United States, the Queen sent a large wreath of white tuberose to the funeral. The wreath was placed on the President’s casket as his body lay in state in Washington, D.C. and during his funeral in Cleveland.

Lucretia Garfield was so touched by this gesture and the Queen’s handwritten note that she sought to preserve the wreath (along with many other funeral flowers and artifacts) after the funeral. She sent it to Chicago to be preserved using a wax treatment. Today, visitors to James A. Garfield National Historic Site can see the wreath displayed in the Memorial Library vault.

Wikipedia

Ironically, the Queen and her husband were both 42 at the time of his death, and Mrs. Garfield and the President were both 49 when he died. Queen Victoria and Lucretia Garfield would each live nearly 40 years after their husbands’ deaths. The Garfield’s oldest child, Harry, was nearly eighteen, and their youngest, Abram, was almost nine when their father died. Princess Victoria was 20 years old at the time of her father’s death; the youngest princess, Beatrice, was just eight.

The Queen, monarch of one of the world’s richest empires, entered widowhood with the advantage of not having to worry about her family’s finances. Though she had more domestic help available to her to assist with her large family, as Queen she had the added burden of ruling the British Empire.

Conversely, though relieved of her public role, Lucretia Garfield was faced with the daunting task of providing her young family both emotional and financial support. She moved back to the Mentor home and competently managed the family farm while raising and guiding her young children. A public subscription fund was started for the Garfields which eventually raised around $350,000. These funds, which would equal about $8 million today, allowed Lucretia Garfield to make a number of improvements to her Mentor property and home, including constructing the Memorial Library.

Library of Congress

For both women, preserving their husband’s memories was very important. Queen Victoria left untouched several of the rooms Prince Albert had used. For the rest of her life, she also had a set of his clothes placed on his bed every day. In her Mentor home, Lucretia Garfield decided to leave the President’s office (what she called “the General’s snuggery”) the way he had left it when they moved into the White House – with few exceptions. Her most meaningful change was this: she had the words “In Memoriam” carved into the wood over the fireplace. “In Memoriam,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson was their favorite poem.

In a new addition to the home, Lucretia Garfield also went to work on cataloging and organizing her husband’s papers, which covered his nearly 20-year public career. The papers were eventually stored in the Memorial Library vault that still holds the Queen Victoria wreath. (Garfield’s papers, stored in the vault for about 50 years, now reside in the Library of Congress.)

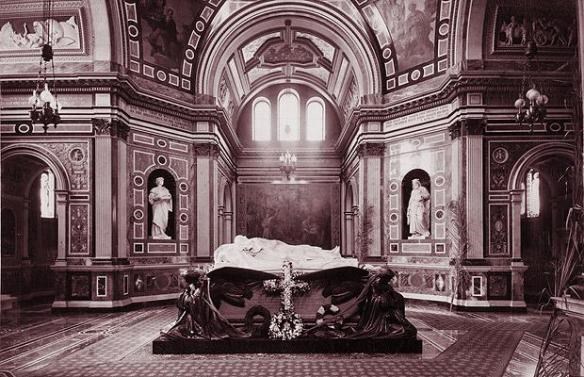

After President Garfield died, his wife and others began to work on a proper memorial to serve as his final resting place in Cleveland’s Lake View Cemetery. A large fundraising campaign ensued that eventually raised $135,000 to build the massive and beautiful Garfield Memorial, dedicated on Memorial Day 1890. Mollie Garfield, the only surviving daughter of the couple, wrote this in her diary after her father’s death: “It is something really beautiful to see how much the people had gotten to love Papa through his sickness. He would be deeply touched.” The President’s remains were moved into the Memorial, and Lucretia’s remains were placed by his side following her death on March 13, 1918.

www.telegraph.co.uk

In the prime of life, few are prepared for the death of a spouse. Mrs. Garfield and Queen Victoria, though, met the challenges that faced them. In their private lives as widows, they raised their young, fatherless children by themselves; they devoted themselves to keeping the memories of their husbands alive for themselves, their families, and the public; and they both mourned the loss of their beloved husbands for the rest of their lives.

www.midwestguest.com