Last updated: October 28, 2020

Article

The Federal Civil Service and the Death of President James A. Garfield

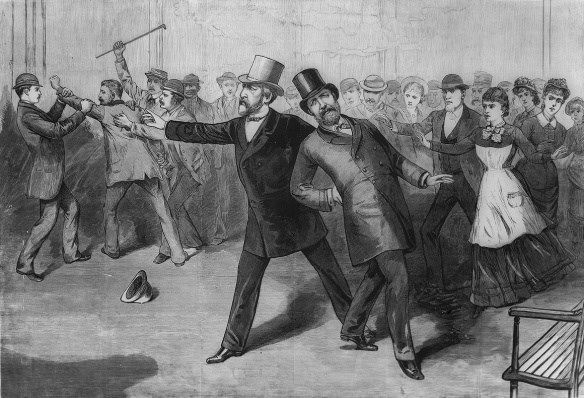

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

Any standard history textbook today will tell you that Charles Guiteau, the assassin of James Abram Garfield, the twentieth President of the United States, was “a disappointed office seeker.” That’s an accurate description, as far as it goes, but there is much more to the circumstances of President Garfield’s tragic murder than that simple phrase suggests. The assassination of James Garfield was not the product of a pathetic, demented megalomaniac; it had its origins in the domestic politics of his time.

By that I mean to say that it was the political culture of the 1860s and 1870s that led to the President’s death in 1881. Specifically, it was “the spoils system” that was as much the cause of Garfield’s assassination as were Guiteau’s actions.

The Federal bureaucracy had been growing since the days of Andrew Jackson in the 1830s. Many government employees working in federal agencies owed their positions to the Congressmen and Senators who had recommended their appointments to the President. These workers were expected to perform political work for their patrons as part of the job. Federal employees were also “assessed” a portion of the salaries, usually about five percent, to fund campaigns.

Reform-minded individuals in the political parties and in the press wanted to put an end to this kind of thing. The first legislation to reform the Federal civil service appeared in December 1865 when Rhode Island Congressman Thomas Allen Jenckes introduced a bill to create a Civil Service Commission, to formulate rules for civil servants, and establish examinations for certain positions in the federal service. Jenckes’ 1865 bill did not pass.

In 1871, Congress finally passed legislation permitting President Grant to create the first Civil Service Commission. Congressional support was not strong, however, and Grant abandoned the effort.

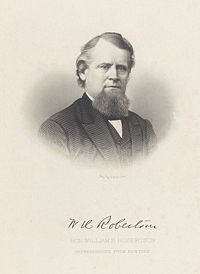

Library of Congress

Grant’s successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, was determined to reform the federal civil service, and in doing so, he confronted the colorful New York Senator, Roscoe Conkling. He battled Hayes’ attempts to reduce his influence with civil service appointments in his state, mainly through replacing Conkling’s henchmen at the Port of New York, including the Collector, Chester Alan Arthur. It was this 1870s political donnybrook that would lead to assassination in 1881.

By attacking Arthur, Hayes was attacking Conkling, and Conkling fought back. In the end, though, Hayes was triumphant, and Arthur was gone – but not for good!

Wikipedia

The Hayes-Conkling fight in 1877-1878 became the Garfield-Conkling fight three years later. Just as Rutherford B. Hayes had wanted to reduce the influence of Senators – and specifically Senator Conkling – in making presidential appointments, so too did James A. Garfield. During his own squabble with Roscoe Conkling, he confided to his diary in the spring of 1881 that he was bound to determine “whether I was the registering Clerk of the Senate or the Executive of the government.”

What were the circumstances that caused President Garfield to make that comment? To begin with, President Hayes did not seek re-election in 1880. James Garfield was nominated after the leading contenders, including former President Grant, were unable to prevail. Conkling had strongly supported Grant, and he was displeased by Garfield’s surprise nomination.

After Garfield won the election, Senator Conkling, ever the power broker, tried to win concessions from Garfield over control of New York political appointments.

In the fall and winter of 1880-1881, the president-elect needed to satisfy the various factions in the Republican Party regarding his cabinet and various diplomatic and domestic posts. Senator Conkling, meanwhile, sought to insure that the political attacks he had suffered under President Hayes would not be repeated by the new President.

Wikipedia

In January 1881, Garfield was fully aware of the need to accommodate Conkling as much as possible. The President-elect invited the Senator to his Mentor, Ohio home to talk. Conkling’s response to the invitation hinted ominously at his future course if his demands were not met: “I need hardly say that your administration cannot be more successful than I wish it to be.” The meeting was not a great success and the tensions between the two continued.

Nevertheless, President Garfield nominated five New York Stalwarts for government posts on March 22. He also nominated William Robertson, Conkling’s adversary, for that most important post of Collector of the Port of New York. Robertson’s nomination was a bombshell, recognized throughout the Republican Party and the national press as a challenge to Conkling.

A compromise intended to achieve peace with Conkling fell through when Conkling reneged on a promise to meet with Garfield. When Garfield heard this, he refused to rescind Robertson’s nomination to the Collectorship.

Politico.com

The situation was once again in turmoil due to Conkling’s peevishness, and as Kenneth D. Ackerman writes, “James Garfield seemed to cross a psychological bridge…Conkling could not be dealt with nor tolerated.” Whitelaw Reid, the publisher of the New York Tribune, wrote to Garfield, telling him that this latest crisis was the turning point of his administration. If Garfield surrendered, Conkling would in effect be the President of the United States. Garfield’s response indeed showed backbone: “Robertson may be carried out of the Senate head first or feet first…I shall never withdraw him.”

At this point, let us turn our attention away from president and the senator and introduce into the narrative President Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau.

Guiteau was born in Illinois in September 1841. His journey through life up to the time of the assassination had been a troubled one. His mother died when he was seven, and his father, Luther Guiteau, was often abusive toward him. As an adult, he pursued a career in the law, and then took up theology. He was successful at neither.

Charles Guiteau was a megalomaniac, and in 1880, having failed so far in life, he came to believe that his way to fame and fortune was in politics. He went to New York after Garfield’s nomination, where he ingratiated himself with Republican officials. He altered a pro-Grant speech he had written to a pro-Garfield speech. He got permission from the Vice Presidential nominee, Chester A. Arthur, to deliver it at a rally for the Republican ticket. When the Garfield-Arthur ticket won in November, the self-deceiving Guiteau believed that he was instrumental in the victory. Therefore, he reasoned, he deserved a political reward: a job in the government.

He believed that he would make an excellent Consul to Paris – even though he had no prior experience in diplomatic service. He made repeated attempts to see President Garfield about it. Guiteau also badgered James G. Blaine, Garfield’s political confidante and Secretary of State. Early in the administration, Guiteau regularly visited the Secretary of State at his office.

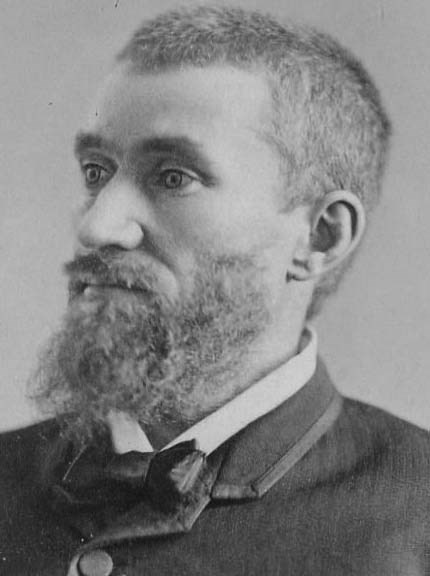

Wikipedia

While Guiteau was making his maneuvers, the fight between President Garfield and Senator Conkling was coming to a head in the U.S. Senate. The President of the Senate was Garfield’s Vice President, Chester Arthur. The role he chose to play in the fight between his mentor, Roscoe Conkling and his President, James Garfield, must be one of the most remarkable in the history of the nation.

Chester Arthur, of course, was the man President Hayes had fired from the Collectorship of the Port of New York in 1878. He had become the vice presidential nominee in 1880 though Conkling urged him to drop the idea as if it were “a red hot shoe from the forge.” Arthur did not. The Vice Presidency was, he said, “a greater honor than I ever dreamed of attaining.”

Arthur and Conkling were a team in the effort to block the nomination of Robertson. On April 2, according to Kenneth D. Ackerman, Chester A. Arthur, Vice President of the United States, gathered together several New York associates “to plan the defeat of his own president’s most important political decision to date,” to kill the Robertson nomination. He saw no irony in this.

When Garfield withdrew all the New York nominations except Robertson’s to force a vote on Robertson, Roscoe Conkling and the junior New York Senator, Tom Platt, resigned their seats. They planned to return to Albany and win reelection. In so doing they would return to Washington politically stronger and able to defeat the President. Chester Arthur even went to New York to lobby on their behalf!

At this point, events moved quickly. With Conkling and Platt gone, the Senate ratified Robertson’s nomination on May 18. President Garfield had achieved an important political victory – but it was a victory that would cost him his life.

It seemed that the Republican Party was becoming more divided. The deranged Charles Guiteau, disappointed in his own hopes for the Paris Consulate, believed that Garfield had to be “removed” in order to save the Republican Party and the country. He purchased an English bulldog revolver – with borrowed money – from a shop in Washington. He saw himself as a patriot and believed that the American public would rally to his support. He also believed that God – “the Deity” was the term he used – was telling him to remove President Garfield.

Guiteau began stalking Garfield. One morning in June, he followed him to the Disciples church where the President worshipped. Guiteau couldn’t shoot a man at his devotions.

Next, Guiteau followed Garfield to the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station on June 18. The President was accompanying his wife Lucretia to New Jersey, where she was to complete her recuperation from an attack of malaria. Guiteau couldn’t shoot Garfield there, either. Mrs. Garfield looked so frail, standing by her husband, that Guiteau said later that he “did not have the heart to fire upon him.”

On a third occasion, Guiteau watched the President and his Secretary of State, James Blaine (who had been so rude to him) walking arm in arm on a Washington street one evening. He followed the pair for some time, but did not act.

But Guiteau knew that he had one more chance to remove the President. It was announced in the newspapers. President Garfield would be taking a train to New Jersey, on Saturday, July 2 to meet his wife and continue on to a vacation in New England and New York. The train would depart the Baltimore and Potomac Train Station at 9:30 a.m.

www.touring-ohio.com

This time he was prepared to act. He knew he would be arrested, so a few days before he checked out the Washington Jail. He thought it would be a nice place to be confined.

Guiteau was already at the station when the President arrived a few minutes past nine, with Secretary Blaine by his side. The President and Secretary were crossing into the main waiting room when Guiteau fired two shots. One grazed Garfield’s right arm, while the other tunneled into his back. The President collapsed.

Charles Guiteau was immediately apprehended. Addressing one of the arresting officers, he said, “I did it. I will go to jail for it. I am a Stalwart and Arthur will be President.”

Guiteau became something of a celebrity in the press; his photograph was taken many times, and interviews and articles by and about him appeared in print. He always insisted that he was the agent of “the Deity” and that what he had done was for the good of the country. Garfield lingered for 80 days before dying on September 19, 1881. Guiteau, so sure he would be revered for his actions, was hanged on June 30, 1882, two days shy of the first anniversary of his attack on President Garfield.

It is worth noting that the National Civil Service Reform League took advantage of President’s assassination by distributing a letter nationwide connecting the “recent murderous attack” on Garfield to promote reform legislation. That legislation, the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, was signed into law by President Arthur on January 16, 1883.

So, President James Abram Garfield was assassinated not simply because a mentally deranged individual was “a disappointed office seeker”; a long-standing and divisive effort to reform the machinery of the Federal government created such a poisonous political atmosphere that that same disturbed individual saw himself as the person equipped to put and end to this factional and personal dispute. Regretably, his solution robbed the country of the leadership of the intelligent, thoughtful, talented man who was the 20th President of the United States.

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, September 2012 for the Garfield Observer.