Last updated: April 4, 2024

Article

The Failure of Grant & Ward: A Cautionary Tale

Library of Congress

Ulysses S. Grant transitioned into a new phase of his life in 1880. Grant and his wife Julia had no permanent home to go to following the end of their world tour the year before. He had lost the Republican Party’s nomination for president, ending his role as a prominent politician. They began considering where they would live out their retirement years and decided they would settle in New York City, where three of their four children were currently residing. In the absence of a steady pension (presidential pensions were not established until 1953), several friends and financial elites sought a way to help provide financial stability for the Grants. According to historian Geoffrey Ward, “twenty Wall Street admirers raised a $250,000 trust fund for [Grant] in gratitude for his service to the Union.” Meanwhile, Grant’s longtime friend George W. Childs, along with bankers Anthony Drexel and J. Pierpont Morgan, contributed $100,000 to help the Grants purchase a home at 3 East 66th Street near Central Park.

Grant, however, was not satisfied with living a quiet life in retirement. Anxious to continue participating in the business world, he was elected President of the Mexican Southern Railroad. His second son, Ulysses “Buck” Grant, Jr., also made an enticing offer. He had previously established a partnership with Ferdinand Ward, a promising Wall Street investment banker. Buck discussed with his father the idea of becoming a partner. Grant happily accepted the offer and invested $50,000 into the firm. With these funds Ward proposed to invest in everything from railroads and construction to silver mines and government contracts. In return, Ulysses and Julia were guaranteed $2,000 every month ($63,000 in today’s money) while the rest of the profits were re-invested into the firm. Each Grant son—Fred, Buck, and Jesse—also invested in the firm. “Grant & Ward” soon became a well-known Wall Street entity.

On the surface, everything worked according to plan. General Grant’s involvement with the firm generated new investments from many business interests in New York City. Ward bought a fabulous 25-acre mansion in Connecticut, while the Grants became millionaires. Grant, who did not oversee the daily operations of the firm, admired Ward’s ability to generate huge investment returns for himself and other creditors.

The reality of the situation was more complicated. Ward was secretly running what is known today as a Ponzi scheme. Early on, Ward recruited investors with the promise of high returns. As new investors heard about the high returns, they contributed funds that were then used to pay off the earlier investors. The scheme relied on a constant flow of new investors to inject funds into the firm to pay off earlier investors. Ward himself also took much of the firm’s money for his personal accounts. By March 1884, the steady flow of new investors was decreasing. Ward realized that Grant & Ward was becoming insolvent.

Ward went to Grant’s home unannounced to discuss the situation with the former general and president and Buck. A large city contract had unexpectedly withdrawn funds from the firm and reserves were getting low. Without a cash infusion, Grant & Ward would dissolve. Ward claimed to the Grants that he had raised $230,000 (in reality, he had been turned down by several banks earlier in the day). Would General Grant be willing to raise another $150,000 to right the ship? Although he did not know him well, Grant considered reaching out to railroad magnate William Vanderbilt, who lived a block away from his residence.

Grant arrived at Vanderbilt’s office later in the day. Embarrassed, Grant explained to Vanderbilt that the firm was in danger of collapsing if not for this cash infusion. Vanderbilt explained that he had never given a personal loan before and that he considered such loans a bad business practice. However, he appreciated Grant’s legacy as the general who saved the nation during the Civil War. “To tell you the truth, I care very little about Grant & Ward,” Vanderbilt admitted, “but to accommodate you personally I will draw my check for the amount you ask. I consider it a personal loan to you, and not to any other party.” After the meeting, Grant endorsed the check over to Grant & Ward.

Ward took the $150,000 loan from Vanderbilt for himself and fled New York City. On May 4, 1884, General Grant met Buck at the firm’s Wall Street office. A reporter who was present at the meeting noted that Buck passed along the news that “Grant & Ward has failed, and Ward has fled. You’d better go home, Father.” A stunned General Grant remained in the building in silence until 5:00PM. Before leaving the office, he remarked to his clerk that “I have made it the rule of my life to trust a man long after other people gave him up, but I don’t see how I can ever trust any human being again.” Moreover, the previously established $250,000 trust fund had been invested in bonds for the Wabash Railroad, which was about to fail. Ulysses and Julia Grant ended the day with $210 to their names, the total amount of cash they had on hand when Grant & Ward failed.

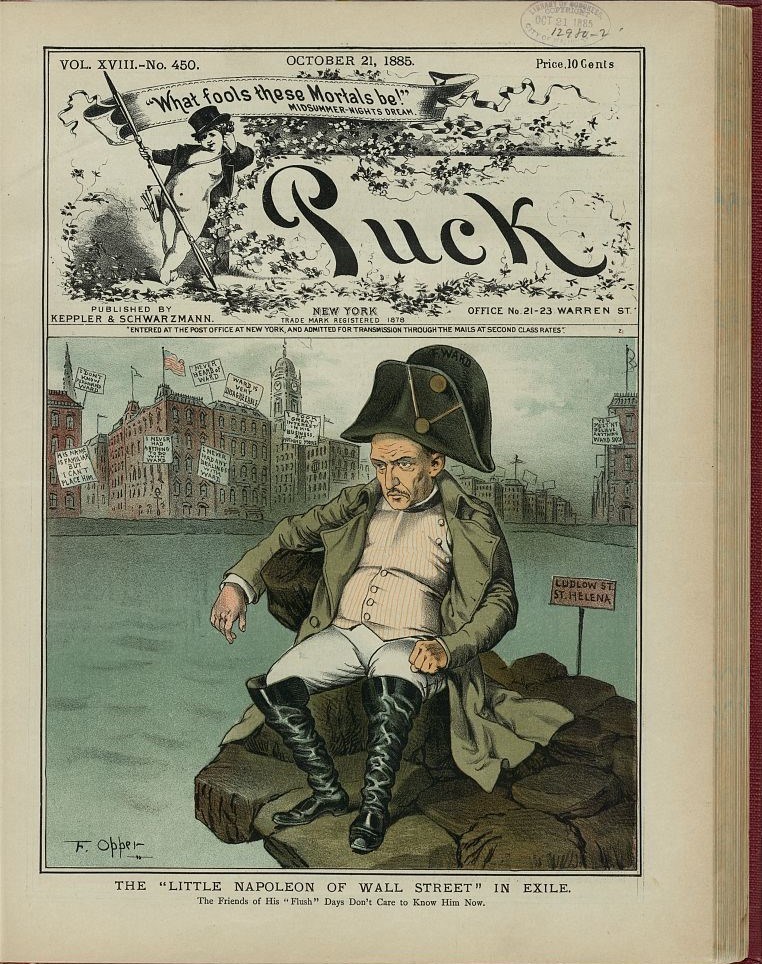

The collapse generated international news, bankrupted many of the firm’s investors, and caused a partial economic panic in which creditors began calling in their investments with other banks in New York City. Ward was eventually arrested and put on trial, but many investors refused to testify because they did not want to be seen as having been duped by “The Young Napoleon of Wall Street.” When news later broke that Grant had been diagnosed with inoperable throat cancer, many newspapers argued that his sickness was Ward’s fault. Ward was eventually found guilty of fraud and sentenced to ten years at Sing Sing Prison, although he lived very comfortably thanks to gifts from supporters and was released after only six years.

For Grant, his first concern was paying his debt to William Vanderbilt. Although Vanderbilt stated that the loan was forgiven, Grant insisted on paying it back. He gathered artifacts from the Civil War and gifts from the world tour and gave them to Vanderbilt, who later donated them to the Smithsonian. He also transferred ownership of the White Haven estate in St. Louis, Missouri, to Vanderbilt as a partial payment. Grant’s second concern was providing for his family. He began writing The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, which were published after his death on July 23, 1885. The memoirs became a bestseller, with the first check to Julia Grant made out for $250,000.

As Geoffrey Ward argues, Grant’s “personal honesty was never questioned,” but “he had shown a fatal inability to recognize dishonesty among those who purported to be his friends.” This character flaw contributed to his struggles in the business world throughout his life. While Grant courageously fought to pay back his debts while dealing with the pains of cancer, his trusting nature caused financial ruin and untold stress in his last days.

Further Reading

Chernow, Ron. Grant. Penguin Press, 2017.Smith, Jean Edward. Grant. Simon & Schuster, 2002.

Ward, Geoffrey G. A Disposition to Be Rich: How a Small-Town Pastor's Son Ruined an American President, Brought on a Wall Street Crash, and Made Himself the Best-Hated Man in the United States. Knopf, 2012.