Last updated: June 27, 2021

Article

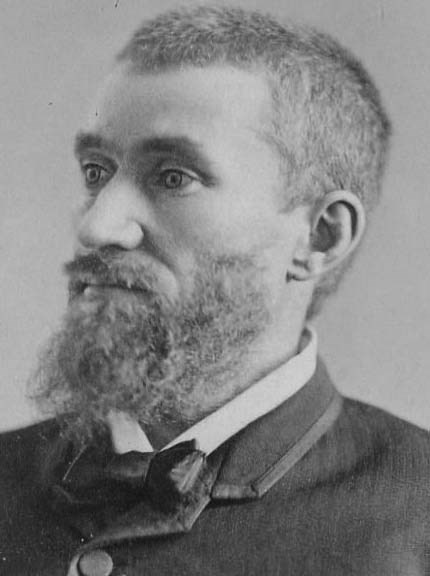

The Execution of Charles Guiteau

Library of Congress

On June 30, 1882, Charles Julius Guiteau was led to the gallows and executed for murder. Guiteau was no ordinary killer, though: his victim was James A. Garfield, the twentieth President of the United States. Guiteau stalked President Garfield around Washington, D.C. for several weeks before shooting him in a train station on July 2, 1881. Garfield had been president for just four months.

Even by nineteenth century standards, Guiteau was obviously mentally ill. He considered himself a loyal Republican, and his narcissistic personality convinced him that his work for the party was critical to Garfield’s election to the presidency in 1880. In fact, Guiteau had made just a few speeches in New York to small and disinterested crowds; the speech itself, which he originally prepared based on the assumption that Ulysses S. Grant would be the presidential nominee, was nonsensical. Guiteau simply went through the speech, crossing out any mention of Grant’s name and replacing it with Garfield’s.

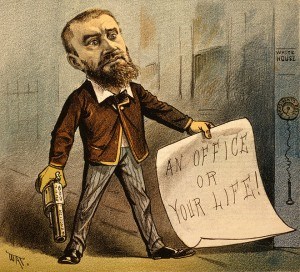

Puck

When Garfield took office in early 1881, Guiteau made his way to Washington to collect his reward: a plum patronage job that he was sure was his for the taking. He visited both the White House and the State Department on multiple occasions to plead his case for an overseas posting to Paris or Vienna. Clearly unqualified, he eventually so annoyed Secretary of State James Blaine that Blaine angrily told him, “Do not ever mention the Paris consulship to me again!”

Garfield was soon embroiled in a very public squabble with New York’s powerful senior Senator, Roscoe Conkling, over the nation’s most coveted patronage job: Collector of the Port of New York. Conkling eventually resigned from the Senate to protest Garfield’s choice for the job. Convinced that Garfield was going to destroy the Republican Party by scrapping the patronage system, Guiteau decided the only solution was to remove Garfield and elevate Vice President Chester A. Arthur—a Conkling acolyte—to the presidency. This would not only save the party, but would also result in Guiteau receiving the patronage job he believed was rightfully his. Surely a grateful President Arthur would reward Charles Guiteau.

Guiteau’s plan did not work out as he envisioned. President Garfield survived for eighty days after being shot, suffering horrendous medical care from doctors untrained in Listerian antiseptic methods. When Garfield finally died on September 19, the government prepared to try Guiteau for murder. At trial, the assassin Guiteau stated that, “I did not kill the President. The doctors did that. I merely shot him.” The jury did not agree, and after a trial that lasted nearly two months and often had a circus-like atmosphere, Guiteau was convicted of murder in January 1882.

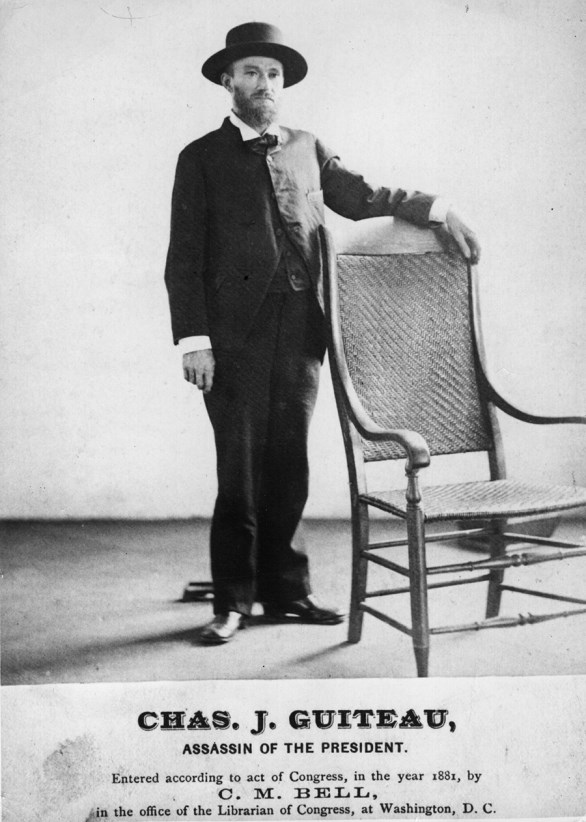

Library of Congress

It was just two days shy of the one-year anniversary of Guiteau’s attack on President Garfield. Before his sentence was carried out, Guiteau was permitted to recite a poem he had written entitled “I am Going to the Lordy.” These were his final words.

I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad,

I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad,

I am going to the Lordy,

Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah!

I am going to the Lordy.

I love the Lordy with all my soul,

Glory hallelujah!

And that is the reason I am going to the Lord,

Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah!

I am going to the Lord.

I saved my party and my land,

Glory hallelujah!

But they have murdered me for it,

And that is the reason I am going to the Lordy,

Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah!

I am going to the Lordy!

I wonder what I will do when I get to the Lordy,

I guess that I will weep no more

When I get to the Lordy!

Glory hallelujah!

I wonder what I will see when I get to the Lordy,

I expect to see most glorious things,

Beyond all earthly conception

When I am with the Lordy!

Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah!

I am with the Lord.

Upon completion of his recitation, the executioner placed a hood over Guiteau’s face and the noose around his neck. Guiteau continued to hold the poem in his hand; he had arranged with the executioner beforehand to drop the paper when he was ready to die. When he did so, the trapdoor opened and the noose broke Charles Guiteau’s neck. His body was buried in the jail yard, but later disinterred and sent to the facility that eventually became the National Museum of Health and Medicine. His brain and enlarged spleen were preserved.

For most of the country, Guiteau’s death marked an end to the year-long saga of President Garfield’s assassination. For the Garfield family, though, the pain and sadness of the previous year would continue for years and decades to come.

Written by Todd Arrington, Site Manager, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, June 2017 for the Garfield Observer.