Last updated: March 3, 2023

Article

The Emergence of a National Historic Site

NPS

The Emergence of a

National Histoic Site: St. Paul's Between the world wars

Text of an exhibition on display in the visitors' center/museum, through January 2025.

Introduction:

The 1920s and 1930s marked a watershed in the development of St. Paul’s as a national historic site. The church was a functioning Episcopal parish in those decades, with a history stretching back to the 1600s. Its chief function was the spiritual and religious lives of the congregation. But under the leadership of Rev. Harold Weigle, the church also began to realize the potential for development of the grounds as a national historic site.

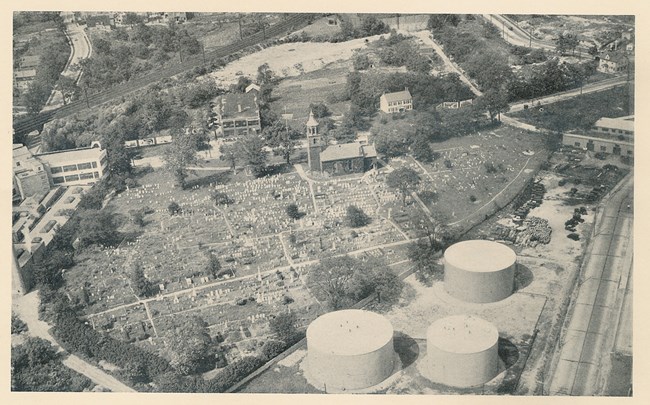

Almost all the physical and cultural landscape of what is today St. Paul’s Church N.H.S. was conceived or developed in those years. The historic section of the burial yard was re-formulated as a historic walking space, partly through the use of Federal relief funds. The appearance and understanding of the eastern side of the cemetery, still under the jurisdiction of the City of Mt. Vernon, was altered with the elimination of further trench burials and the end of use of the section as a potter’s field.

The building where this exhibition is displayed was re-built as a hall for people, rather than horses, who had been the occupants for the previous 90 years. The development of this southern section of Mt. Vernon as an industrial corridor eclipsed a traditional rural landscape that had defined the area since colonial times. This led to the forced departure of a remarkable African American family that had lived just off the church grounds since the early 1800s. The restoration of the interior of the church to the original 18th century design and appearance was imagined and planned during those years of the Great Depression.

All these changes transpired against a remarkably diverse historical backdrop of the period between the world wars. The prosperity of the 1920s, and the emerging domination of the automobile, helped to define the patterns of change in the period immediately after the First World War. The searing impact of the Great Depression of the 1930s, ironically, created the circumstances for some of the major alterations to the church and burial yard. We invite you to learn about this transitional chapter in the history of the church through documents, artwork, photographs, sound, text, and artifacts.

Panel 1: St. Paul’s in the 1920s

The years following World War I marked an important transition period for St. Paul’s Church. The changes were symbolized by the transformation of this building. The earliest structure on this site was a wooden horse shed built in the 1830s, serving the parish community at a time of horse drawn carriages. In the late 1880s, an endowment from a wealthy woman who was a parishioner had facilitated the erection of a handsome masonry carriage house. But by the mid-1920s, the rapidly developing popularity of the automobile had rendered a carriage house unnecessary and obsolete. What, then, to do with this building?

The introduction of the automobile and the general prosperity of the decade also contributed to the transformation of the surrounding community. In 1920, there were still several 18th century homes in the immediate vicinity, left over from an earlier time when most people lived near a church, which was the religious, political, and social center of a town. This pre-industrial character of the area had been changing slowly, for many years, but the pace of transformation was greatly increased during the Roaring 20s. People moved away, to more pleasant Westchester suburban communities, or further. The automobile could take you anywhere, symbolized locally by the opening of the Hutchinson River Parkway in 1928. Census figures showed one car registered for every 7.2 persons in Westchester in 1922. By 1930, there was one car registered for every 3.7 persons, recording the highest per capita of automobile ownership of any county in the nation.

This pattern of residential abandonment of the St. Paul’s vicinity led the local municipalities -- Mt. Vernon, but also the adjoining section of the northern Bronx -- to re-classify the zoning use of the communities as commercial/industrial. These new regulations accelerated changes in the landscape of the St. Paul’s area.

The church decided to turn the carriage house into an all-purpose parish hall, something the church, founded as a parish in the 1660s, had never really had. Loans were secured, pushing the church into debt, and the building we now occupy was completed in 1925 (see cornerstone outside, front). The development of the auxiliary building here as a community center rather than a horse carriage house was an important point of transition of St. Paul’s becoming a historic site. It facilitated commemorative, recreational, and public events that were not previously possible. Franklin D. Roosevelt and other important visitors attended events in the parish hall.

Panel 2: Rev. Harold Weigle and the vision of a national historic site

The installation of Rev. Harold T. Weigle as the St. Paul’s minister in 1929 ushered in a new era in the history of the church and the real beginning of the development of the grounds as a national historic site. An enormously energetic and ambitious clergyman, Rev. Weigle and his wife Anna had served as Protestant missionaries for several years in China following graduation from Cornell University in 1921. Their two children were born in Asia. A minister with a wife and two young children could have trouble obtaining a position at more prestigious Episcopal churches. That was perhaps why he accepted the calling to St. Paul’s, well removed from New York City and evidently a parish in decline, experiencing difficult changes from a residential community to an industrial corridor.

But Rev. Weigle clearly wanted to make something out of the church, and in addition to his religious responsibilities as minister, he seized upon the historical setting and heritage of the site. In particular, he grasped a landmark, open air election held on the village green at St. Paul’s in 1733, as the cornerstone of building a historic shrine. The election’s extensive coverage in the first issue of The New York Weekly Journal, printed in New York City by John Peter Zenger, and subsequent developments, particularly the trial and acquittal of Zenger on charges of seditious libel, were landmarks in the development of freedom of the press in America. They were understood as an early symbol of the themes eventually enshrined in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. (Other historians and writers had also valued the significance of the election of 1733 and its aftermath, but Rev. Weigle interpreted the event’s consequences much more broadly.)

The minister’s relentless focus on these themes, and development of many public programs to increase appreciation of them, generated enormous attention and publicity for the church. It changed from a quiet, if historic, Episcopal church to a major source of focus and attention. Rev.Weigle had many friends in the theatrical world from an earlier period as a minister at The Little Church Around the Corner in Manhattan, attended by many Episcopal actors and actresses. He utilized those connection to stage public events. The largest of these was a series of re-enactments of local historical episodes and pageants on June 14, 1931. The event drew an estimated 7,000 people to the church grounds, the largest gathering in the centuries-old history of St. Paul’s. The keynote address was delivered by Governor (and future President) Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was a distant relative of an 18th century congregant.

Launching from that high profile event, the church began a campaign of publicity, networking and fundraising intended to create permanent shrines to the 1733 election and, by extension, the origins of the freedoms articulated in the Bill of Rights. With assistance and support from Sara Delano Roosevelt, F.D.R.’s mother, those tiresome efforts continued into the early 1940s, culminating in the restoration of the church interior to the original 18th century appearance, which even today forms the cornerstone of historical tours of St. Paul’s. It was declared a national historic site in 1942.

Panel 3: Civil Works and the transformation of the cemetery

The high levels of unemployment and social dislocation of the Great Depression actually helped create the circumstances for a modernization of the historic St. Paul’s cemetery, one of the nation’s oldest burial yards, with legible stones dating to 1704. One of the first of the relief agencies created in 1933, as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal initiative, was the Civil Works Administration (CWA). The agency was designed to generate short term employment for people out of work through readily available, easily conceived projects -- work on public buildings, fixing fences at parks, bridge, tunnel and road construction, sewer repair. Later New Deal agencies, the Public Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration, employed greater numbers of people and developed some of the lasting imprints on the infrastructure of the country.

But the CWA preceded those agencies, and, unlike those later public works initiatives, it also funded projects on private property, like St. Paul’s, and furthered Rev. Weigle’s vision of the church as a modern historic site. St. Paul’s received $34,000 (about $740,000 in today’s money) in March 1934 to cover labor costs for a variety of projects on the church grounds. These included establishing dry wells (still there) in the cemetery to control possible flooding that might threaten the church and the stone wall (still present) along the sidewalk of South Columbus Avenue.

The most ambitious was an extensive, and controversial, project to remove and re-position gravestones in the cemetery. Scores of footstones – originally placed about six feet behind the headstone to mark the end of a grave location -- were re-set directly behind the headstone, facilitating improved touring of the yard. In addition, many late 19th and early 20th century vertical granite gravestones were placed down on the ground, horizontal, since they were not marble or sandstone. Those burial stones from the 18th and 19th centuries were perceived as more historically significant and representative of the landscape Rev. Weigle was trying to establish. Granite tombstones, common by the 1930s, were rejected and disallowed, as “too modern, and not Colonial,” the church charged, leading to legal action in at least one case by a monument maker who supplied a granite stone on the orders of an executive of an estate. Burial plot iron work, which had marked and set off family plots, was also removed, and many stones were re-positioned to form straight rows.

The physical landscape of the cemetery was transformed in a way which some critics claimed altered the historic character of the grounds, but probably helped create the modern infrastructure for a national historic site. These changes greatly enhanced the ability of visitors to stroll through and gain an appreciation of the history of the five-acre burial yard. Those transformations remain evident and still facilitate the core of the site’s interpretive tours.

Panel 4: The Great Depression and the St. Paul’s area

The Great Depression of the 1930s had an enormous impact on life and people in America. Long bread lines, vast increases in homelessness, depravation and young people reduced to riding the railroads were among the most evident manifestations of the crisis. At the depths, in 1932, nationwide unemployment was approximately 25-percent and there were about a million people out of work in New York City.

The economic collapse also produced difficulties and hardships on this community and the parish of St. Paul’s in ways that contributed to the development of the church as a national historic site and led to the final removal of the Turner-Nelson family from their land (explained in another section of this exhibition.) Free food was distributed to local unemployed adults and their families, but Mt Vernon authorities, struggling to keep up with demands, were on the edge of a crisis in supplying staples like butter, milk, and eggs in 1934. Volunteers for the YWCA contributed countless hours sewing clothes for the children of the local unemployed, since regular government relief programs only offered food. Thousands of local men gained wages by working on government sponsored public works in the county, and many of the community’s young men left home to work on Civilian Conservation Corps camps in northern Westchester County.

With the reduction in tax collection because of unemployment, the City verged on municipal bankruptcy, and could not pay the salaries of public school teachers. In this context, with the drive for any possible revenue streams, the foreclosure on the Turner-Nelson homestead near the church and the sale of that land to an oil company comes into focus.

The church also faced financial hardship. In the roaring 20s, taking advantage of favorable economic circumstances, St. Paul’s extended mortgages for home purchases to parishioners who moved into surrounding communities -- a common practice at the time -- with low interest rates. Defaults on those mortgages during the Depression, only a few years later, strained the resources of the church corporation. The Depression circumstances made it difficult to expect direct support from the parishioners, many of whom were out of work. St. Paul’s was forced to “resort to those church suppers, bridge parties and the like which brought in so little money as to make it scarcely worth the time and the effort spent upon them,” according to Anna Weigle, the minister’s wife.

These financial strains were the major reason why the church turned to outside funding for operations and especially the restoration project of the late 1930s. The committee organizing the drive solicited support from wealthy people and organizations that were not impacted by the Great Depression. Those fundraising endeavors helped introduce the church and its history to a broader audience of prosperous and influential people. But they also yielded control of the parish’s operations to the rich donors and created a clash with some long-time congregants who resented the move to recreate the church of the late 18th century.

Panel 5: Cemeteries & History: the end of the potter’s field at St. Paul’s

For many years, the St. Paul’s cemetery consisted of two separate burial yards. The western side, behind the masonry church, was the more historic section, site of the original wooden meetinghouse and of burial markers dating to the very early 1700s. The eastern side, behind what is today the museum, was understood as a public cemetery, under the jurisdiction of the Town of Eastchester and, beginning in 1892, the City of Mt. Vernon. This origin of this distinction was a division between church and town land created after the American Revolution. At one time a fence separated the two sections.

Burials on the City side increased greatly in the 1890s, and interments included many citizens of Mt. Vernon who were not parishioners of St. Paul’s. Families paid a fee to the City for the right to bury loved ones, including Dr. Charles S. Taft, one of the attending surgeons at the Lincoln assassination of 1865. He lived in Mt. Vernon briefly at the end of his life and passed away in 1900. However, by the early 1920s, the area had become increasingly used as a potter’s field, or a burial yard for people who needed public assistance for interment. Use of the area in this manner had existed since at least 1910, reflected in the document on this panel. Many of these interments were very young children, born to families of limited incomes, who died shortly after birth, at a time when infant mortality was still a serious problem in much of America. Others were people who died in local accidents or other circumstances, with no identification, and had to be buried under City jurisdiction. There were eventually 680 burials in these trench graves -- several coffins interred in a large pit, or a trench.

Objections to the trench burials and the potter’s field emerged in the 1930s from the church side under Rev. Harold Weigle, who was developing his conception of the church and grounds as a special national historic shrine. These trench burials seemed to downgrade the significance of the site. The church vehemently argued that the potter’s field also created a public health crisis, with multiple coffins stacked in an increasingly overused section. Efforts to reach agreement with the City failed, and the church began a series of lawsuits, reaching State Supreme Court. St. Paul’s was seeking to end the practice of trench burials and use of the area as a pauper’s field. The legal drama included court-ordered ground probes to determine how many trench burials there were.

The controversy attracted public and local newspaper attention. Fearing a spectacle and unwanted publicity, the probes were conducted at undisclosed times, in secret - at dawn or dusk. The city and the church even disagreed over the results of the probes, with Mt. Vernon clinging to the idea that there remained sufficient room to continue the potter’s field burials. Ultimately, the City agreed with the courts that the trench burials were too numerous, and they ended in 1939. In addition to the tales of spirits and ghosts, the end of those trench burials marked an important development in recognizing the grounds as special and important, helping to build the case for national historic site status.

Panel 6: Depression, Land and Removal: The saga of the Turner/Nelson Homestead

“The land is in your hands. I am the last heir; the city may go right on and do what they like as before. It is now over a hundred years ago, since our dear and godly grandparents, gathered their children for family prayers, morning and evenings, and a blessing at each meal and it was handed down to us, to me, the last heir. Now I can say with boldness their God is my God.”

This powerful statement in 1934, from Sarah E. Nelson, reflects the final chapter of a remarkable story of slavery to freedom, family, land and faith in the shadows of St. Paul’s Church, for more than a century. It began in the early 19th century when Sarah’s grandparents -- Benjamin & Rebecca Turner -- took up residence on a small parcel of land just east of the St. Paul’s Church grounds. Rebecca, born in1781, had been enslaved to a local family, and gained her freedom in 1810, probably with financial assistance paid by her husband Ben to the family that had owned her.

The Turners lived on the land near the church, developing a cabin, a small farm, an advantageous location on the banks of the Hutchinson River, with fish, clams, oysters, and an active bird life. Living within the severe prejudicial restrictions of the 19th century, they established a stable, vibrant family life, raising six children. Ben Turner earned enough public trust to serve as the assistant pounder, gathering up loose and stray animals and holding them on his farm until the owner paid a fine. Turner children attended the local public schools, which operated on an integrated basis.

The Turners attended services at St. Paul’s Church, a short walk from their homes. But they faced the racial exclusions in place at most Protestant churches in the North at the time, including a segregated Sunday school for the youngsters. In the mid 1830s, they joined other African American families to form a separate black congregation, Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church, located around the corner. Ben Turner died in the mid 1830s, and Rebecca, establishing a family laundry business and continuing to manage the farm, possessed the plot for the next 40 years, a rare status for a black woman in New York at the time.

The last heirs

For many years after Rebecca Turner died in 1874 at age 93, followed by burial at St. Paul’s, descendants continued to live on the family land, subsisting in a similar manner, taking in wash. The central characters are her granddaughters, the last heirs, Maria (Nelson) Williams and especially Sarah E. Nelson. Through the early 20th century, they struggled to sustain a livelihood and existence on the homestead, imperiled by the encroachment of industrialization and urbanization. The formerly pleasant residential area was slowly but surely transformed. During this time, they occasionally worshipped at St. Paul’s Church.

The extension of S. Fulton Avenue toward the Hutchinson River increased property values in the area, and their annual assessment and property taxes rose. Sewage in the Hutchinson River corrupted the local ground water, including the well the Nelson sisters used for their personal use and the struggling family laundry business, which was their chief source of income. A local garbage dump, at a time when rubbish in such pits was routinely burned, created a steady stream of ashes, which hampered their ability to keep clothes clean on the line. The growth of taverns and bars in the vicinity affected their quality of life, with intoxicated revelers roaming the neighborhood on many evenings, sprawling into their yard. Employment opportunities for black women were extremely limited at the time. Once economic changes circumscribed and really eliminated the life their grandmother had carved out for them, Maria and Sarah had few options of a different livelihood that might have sustained their presence near the church.

The Nelson sisters moved away in 1910, initially to Tenafly, New Jersey, with a promise of assistance from a former neighbor. But they maintained control of the land, almost certainly visited the old property on occasion, and attempted to keep up on the tax payments. Two noteworthy documents, part of their struggles to maintain the land, form the basis of understanding their attachments, and are prominently included in this exhibition. Foreclosure occurred in 1936, and the land was sold to an energy company a few years later, expanding the reach of Oil City, along the Hutchinson River, behind the church.

Maria died in 1931. With assistance from her sister and other parishioners who fondly recalled the Nelson sisters; she was accommodated burial at St. Paul’s, near other relatives. Sarah, the last heir, living in Nyack, died in 1941, at age 86. Her ancestral connection to the homestead was unknown to her neighbors, and she was buried in a cemetery in that Hudson River town. The renaming of local public schools in the 21st century as the Rebecca Turner Elementary School and the Benjamin Turner Middle School has commemorated the extraordinary story of this family that lived near the church through three generations.