Last updated: December 11, 2021

Article

The Embattled British Column: Survival Against the Odds on the Battle Road

e-mail us

The Mission

On April 19, 1775 Lt. Colonel Francis Smith of HM 10th Regiment of Foot was tasked with what might seem to be an impossible mission. General Thomas Gage, Royal Governor of Massachusetts, ordered him to march with several hundred of his best soldiers to Concord to “seize and destroy all Artillery, Ammunition, Provisions, Tents, Small Arms, and all Military Stores whatever…”What these orders do not convey to us is that Concord is 18 miles from Boston. This makes for a round trip of nearly 40 miles through a countryside where the people, acting in open rebellion, could summon thousands of highly motivated soldiers on very short notice. To accomplish his mission Smith had the grenadier and light infantry companies, elite soldiers, drawn from 11 different regiments in the Boston Garrison. The total strength is estimated at about 700 men.[1]

The mission did not start out well. Fighting erupted at dawn as Smith’s column reached Lexington. The first shots of the war were fired there and the first Colonists were killed. At Concord, most of the military supplies they came looking for had already been moved. Around 9:30 a.m. more fighting broke out at the North Bridge. The first British soldiers died there. Now. for Lt. Colonel Francis Smith, the only remaining priority was to return with his troops to Boston. The British soldiers began the 18-mile march around noon as thousands of rebel militiamen were fast approaching.

At Meriam’s Corner, little more than a mile into the return march and still within the bounds of Concord, militiamen from the towns of Reading, Chelmsford and Billerica arrived and exchanged fire with the British column.[2] The battle now began and continued almost non-stop for the next 16 miles. For the British soldiers, it was now a fight for survival.

The Duke of Northumberland's Estates, Estates office, Alnwick Castle.

How was the march conducted?

Marching a column of troops through hostile territory and bringing them safely home is a complicated and daunting operation. Among the most influential military books of the 18th Century was “A Treatise of Military Discipline” by Colonel (later Lieutenant General) Humphrey Bland. Ownership of one or more copies was very widespread among officers in the British Army at the start of the American Revolution.[3] Not surprisingly, Bland devoted an entire chapter to “…Marching of a Regiment of Foot, or a Detachment of Men, where there is a Possibility of their being Attacked by the Enemy.”Among the key recommendations from Bland was to form strong advance (van) and rear guards. The purpose of the van-guard was “to reconnoiter, or view, every place where any number of men can lie concealed, such as woods, copses, ditches, hollow ways, straggling houses, or villages, through which you are to march or pass near…” The rear-guard was “to take up all the soldiers who shall fall behind the regiment” and to provide security for the rear of the column and prevent it from “being fallen upon (attacked) in the rear, before they have notice to prepare for their defense.” Lastly, in between the van and rear-guard, were “flanking parties.” These were “small parties, commanded by sergeants, marching on the flanks (sides) of the battalion with orders to examine all the hedges, ditches and copses which lie near the road…”[4]

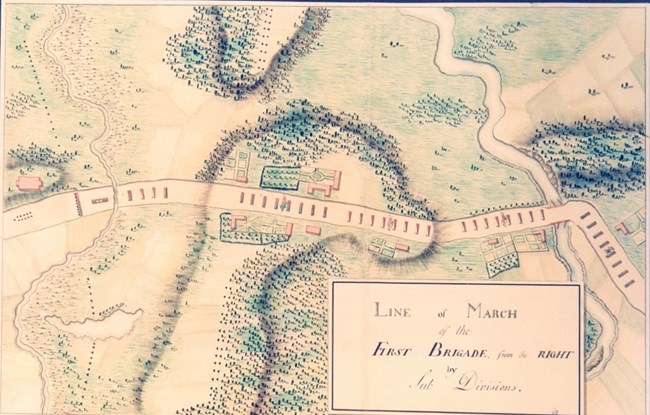

There is strong evidence that Lt. Colonel Smith, and later Brigadier General Hugh Earl Percy who led the reinforcements and assumed overall command that afternoon, organized the column for the return march using the principles laid out in Bland’s “Treatise…” For example, they did not simply form their column in the road and stumble forth into danger. They took care to protect themselves. Ensign DeBerniere, 10th Reg’t of Foot, wrote “…we began the march to return to Boston, about twelve o’clock in the day, in the same order of march, only our flankers were more numerous and further from the main body…”[5] Later, Lt. Frederick MacKenzie of the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, who marched with Percy, wrote that his brigade “… marched in the following order, Advanced guard of a captain and 50 men; 2 six-pounders, 4th Reg’t, 47th Reg’t, 1st Bttn of Marines; 23rd Reg’t, Rear guard of a Captain and 50 men.” This tactic was straight out of Bland’s Treatise.

The Importance of Light Infantry

Smith was also fortunate that light infantry made up half of his force. Light infantry were soldiers specially trained to operate in small units, spread out, take advantage of cover and skirmish with the enemy. The concept was developed in Europe during the 18th century and was employed by the British Army during the last French and Indian War in North America. In 1771 the Army officially added one company of light infantry to each regiment.[6]In the winter of 1775, a physician from Scotland, Dr. Robert Honeyman, travelled to the American colonies. In the later winter of 1775 he was in Boston and observed the light infantry at exercise (drill) on Boston Common.

“Every regiment here has a company of light infantry, young active fellows, and they are trained in the regular manner, and likewise in a peculiar discipline of irregular and bush fighting. They run out in parties on the wings of the regiment where they keep up a constant and irregular fire. They secure their retreat and defend their front while they are forming. In one part of the exercise they lie on their backs and charge their pieces and fire lying on their bellies. They have powder horns and no cartouche boxes.”[7]

Tough Going on the Battle Road

Despite the known principles in Bland’s “Treatise” and the presence of light infantry, the retreat to Boston on April 19, 1775 was tough going. Most of the landscape was open pasture, meadow and tillage fields, crisscrossed with fences of stone and/or wood rails and dotted with woodlots and apple orchards. All of this played much to the Colonists’ advantage. According to Lt. John Barker, 4th Regiment of Foot,Marine Captain William Soutar wrote “Sometimes we took possession of one hill, sometimes of another…”[9] This indicates that the flanking parties were not simply sweeping across the landscape, but actively going out and attempting to control key terrain, like hills. In the tactical analysis from the Parker’s Revenge Archaeology Project in 2015 experts agreed that the broken landscape made it impractical to keep flanking parties out constantly and therefore they were sent out as needed.[10] Imagine keeping that up for 18 miles!“…the Country was an amazing strong one, full of hills, woods, stone walls, &c., which the Rebels did not fail to take advantage of, for they were all lined with people who kept and incessant fire upon us, as we did too upon them but not with the same advantage, for they were so concealed there was hardly any seeing them…”[8]

As the afternoon wore on, the situation became desperate. According to Ensign Henry DeBerniere

“…we at first kept our order and returned their fire as hot as we received it, but when we arrived within a mile of Lexington, our ammunition began to fail, and the light companies were so fatigued with flanking they were scarce able to act, and a great number of wounded scarce able to get forward, made a great confusion. Col. Smith (our commanding officer) had received a wound through his leg, a number of officers were also wounded, so that we began to run rather than retreat in order - - the whole behaved with amazing bravery, but little order; we attempted to stop the men and form them two deep, but to no purpose, the confusion increased rather than lessened: At last, after we got through Lexington, the officers got to the front and presented their bayonets, and told the men if they advanced they should die…”

Earl Percy Arrives with Reinforcements from First Brigade

Sometime around 3:00 p.m. on a hill just east of Lexington center, Brigadier General Hugh, Earl Percy arrived with about 1000 reinforcements from 1st Brigade.[11] The brigade, though delayed, arrived at a critical point. Smith’s column was nearly spent. The men were exhausted and running low on ammunition. Many officers had been hit and panic was setting in.

Despite Percy’s arrival, the soldiers were still many miles out from safety; and the rebels, temporarily dispersed by the sight of the brigade and their two artillery pieces, once again began to press in and attack. According to Lt. Frederick MacKenzie,

“During this time the Rebels endeavored to gain our flanks, and crept into the covered ground on either side, and as close as they could in front, firing now and then in perfect security. We also advanced a few of our best marksmen who fired at those who shewed themselves.”

After about half an hour the brigade moved out. The grenadier and light infantry companies that marched to Concord with Smith’s column were placed at the head of the column which was deemed safer. Lt. MacKenzie continues,

“…our regiment received orders to form the rear guard. We immediately lined the walls and other cover in our front with some marksmen, and retired from the right of companies by files to the high ground a small distance in our rear, where we again formed in line…During that time the flank companies and the other regiments of the Brigade, began their march in one column on the road towards Cambridge…”

The fighting only increased as more and more companies of rebel militia arrived upon the field ready to fight. The more thickly settled areas closer to Boston, like the village of Menotomy (today Arlington), provided a new opportunity for the rebels in their attack upon the army. Lt. MacKenzie wrote

“…we were fired upon from all quarters but particularly from the houses on the roadside, and the adjacent stonewalls. Several of the Troops were killed and wounded in this way, and the Soldiers were so enraged at suffering from an unseen Enemy, that they forced open many of the houses from which the fire proceeded and put to death all those found in them…”

In Cambridge, Earl Percy made a decision that likely saved many lives. The column came to a road junction. The road to the right led southeast through Cambridge to approach Boston from Roxbury. That road crossed Charles River by a bridge which militiamen had taken up and were waiting by in ambush. Percy, instead, took the road to the left which led to Charlestown. This unexpected move temporarily threw off the pursuit.[12]

Despite Percy’s maneuver, more danger lay ahead as a large force of militia from Salem and Marblehead approached from the north. The militia were led by Colonel Timothy Pickering and arrived at Winter Hill just as the British column was approaching Charlestown Neck. For reasons still unexplained, these Essex County men did not attack. Pickering claims that General Heath of Roxbury sent orders to him not to engage and let the enemy escape into Charlestown. Heath denied the claim.[13] What if they had attacked? Would that have spelled certain defeat for the British?

The Fight Ends and a War Begins

Sometime around 7:00 p.m. the battered and bloodied British column withdrew into Charlestown where they formed a defensive position on Bunker Hill. The rebel militia wisely broke off the attack and the day’s fighting came to an end.In a single day the Colonists suffered 95 casualties overall, 49 of which were killed. The British lost 273 soldiers out of about 1700: 73 killed, 174 wounded, 26 missing. By a measure of casualties, the British definitely had the worse day. On the other hand, Smith and Percy were able to bring the majority of their soldiers home after a march of nearly 40 miles, half of which they were under fire and eventually outnumbered more than two to one - a small consolation in an otherwise disastrous mission. In the years to come, the British Army learned the lessons of Lexington and Concord and adapted their tactics, organization and even their uniforms to fighting an American War.

Sources and Notes

[1] French, Allen, “A British Fusilier in Revolutionary Boston: Being the Diary of Lieutenant Frederick MacKenzie, Adjutant of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, January 5 – April 30, 1775”, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1926, pp 51 and 52. The units selected for the mission were the Grenadier companies from the 4th, 5th, 10th, 18th, 23rd, 38th, 43rd, 47th, 52nd and 59th Regiments, and 1st Bttn, Marines, and Light Infantry companies from the 4th, 5th, 10th, 23rd, 38th, 43rd, 47th, 52nd, 59th Regiments, and 1st Bttn, Marines.

[2] Sabin, Douglass, “April 19, 1775, A Historiographical Study, Part IV: Meriam’s Corner”, Minute Man National Historical Park, National Park Service, Concord MA. 1985

[3] Gruber, Ira D. “Books and the British Army in the Age of the American Revolution,” University of North Carolina Press, 2010, pg 150

[4] Bland, Humphrey. A Treatise of Military Discipline: In which is Laid Down and Explained the Duty of the Officer and Soldier, Thro' the Several Branches of the Service. Ireland, D. Midwinter, J. and P. Knapton, 1743.

[5] Account of Ensign Henry DeBerniere, report to General Gage, Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. 4, pgs 215-219. Also published in Kehoe, Vincent, “We Were There! April 19, 1775” 1974

[6] Macniven, Robbie, “British Light Infantry in the American Revolution” Osprey Publishing Ltd, Oxford UK, 2021 pg 11

[7] Honyman, Robert. Colonial Panorama, 1775: Dr. Robert Honyman's Journal for March and April. United States, Books for Libraries Press, 1971.

[8] Atlantic Monthly, Volume 39, “Diary of a British Soldier: John Barker, Lieutenant, King’s Own Regiment” April 1877

[9] Kehoe, Vincent, “We Were There! April 19, 1775: Captain William Soutar, Correspondence” 1974

[10] Watters Wilkes, Margaret, Ph.D “Parker’s Revenge Archaeological Project, Final Report,” submitted to Minute Man National Historical Park, October 2016, pgs 178-180

Parker’s Revenge Battlefield Restoration – Friends of Minute Man National Park

[11] Boston National Historic Sites Commission, “The Lexington-Concord Battle Road Hour-by-Hour Account of the Events Preceding and on the History-Making Day April 19th 1775” Eastern National, 2010, pg 25

[12] Fischer, David Hackett “Paul Revere’s Ride” Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1994. Pg 259

[13] Ibid pg 260