Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Previous: A Society Built Upon Enslaved Labor

Next: Slavery and the Law

Article

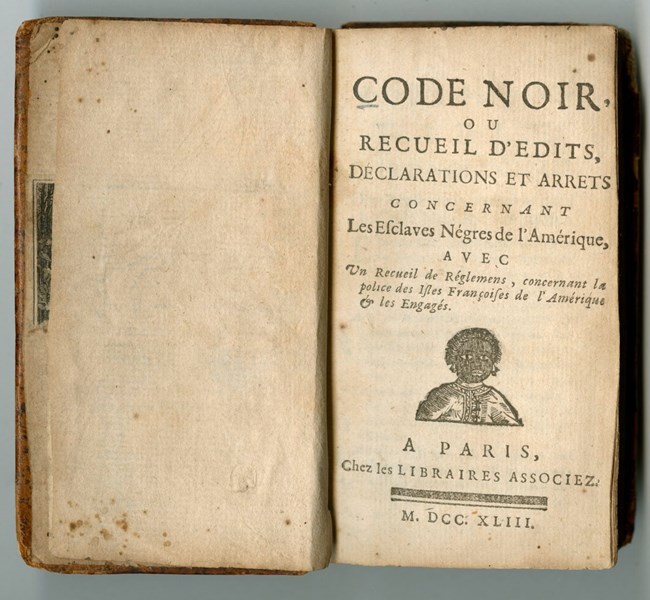

The Historic New Orleans Collection

France and then Spain governed St. Louis for nearly forty years (1764-1803). During this time, slavery was justified and regulated under the Code Noir, which is French for “Black Code.” The French government established the Code Noir to regulate the lives of free and enslaved Black residents in its territories.

The Code Noir had sixty articles (rules). Enslavers were required to feed, clothe, and care for enslaved people. They were also prohibited from breaking up enslaved families through sale. Under Spanish rule, enslaved people had the right to purchase their freedom if their enslavers allowed them to work Sundays and save their money. In contrast to future U.S. laws, enslaved people under the Code Noir could receive an education, own property, and run businesses. These articles also said that enslaved people had to be baptized as Catholics and could not be forced to work Sundays or holidays. Many enslaved people resented having their religious practices dictated by the government.

The Code Noir also used violence and intimidation to keep Black residents in slavery. Any enslaved person who struck their enslaver or a member of their family was to be executed. Enslaved people could not leave their enslaver’s property or own property of their own without permission. They were also prohibited from owning guns. Other punishments allowed under the Code Noir included whippings, branding with a fleur-de-lis, and cutting off ears. Ironically, the fleur-de-lis is a prominent symbol in St. Louis today. It is the official logo for the city’s flag and for Saint Louis University.

Creative Commons/Don Sniegowski

Many people know about the famous Lewis and Clark expedition from St. Louis to the Pacific coast. Less well known, however, is the story of York (c. 1770–c. 1834). William Clark enslaved York, who was forced to leave his family and brought along with the Corps of Discovery when it left St. Louis in May 1804.

York played several crucial roles during the expedition. He hunted and provided food for the Corps of Discovery, even though laws banned enslaved people from using guns. In an incredible act of selflessness, York saved the lives of Clark, Sacagawea (a Lemhi Shoshone woman who assisted the expedition), and her son from drowning during a flash flood.

Upon returning to St. Louis in 1806, every member of the Corps of Discovery received cash bonuses and 320 acres of land for their service. York remained enslaved by Clark for at least another decade. Although York had saved Clark’s life, Clark wrote at one point that York could not be freed because “I do not think . . . that his services [have] been so great [so that] my situation would permit me to liberate him.” While Clark claimed in 1832 that he had freed York, no legal documentation exists to confirm whether he ever received his freedom.

Library of Congress

When Missouri became a U.S. territory in 1803, the legislature wanted to define who could be considered “Black.” New rules stated that “any person who shall have one-fourth part or more of negro blood” was considered Black under territorial law. Black Missourians were subjected to “Black Codes” that succeeded the Code Noir. A person with three White grandparents and one Black grandparent could be legally enslaved in Missouri.

When Missouri applied for statehood in 1819, Congressman James Tallmadge of New York proposed a plan for the gradual end of slavery. This plan included freeing all enslaved children once they reached the age of 25. However, Missouri’s political leaders overwhelmingly supported the continuation of slavery.

Smithsonian Institute

Thomas Hart Benton, a future Senator from St. Louis, even argued that enslaved people would welcome the chance to live in Missouri instead of the Deep South. He believed that enslaved people would be treated well and enjoy a better climate in Missouri compared to other Southern states. Benton was an enslaver for most of his adult life and therefore had a personal interest in Missouri becoming a slave state.

In 1820, Congress passed the Missouri Compromise. This legislation stated that Missouri would enter the Union as a slave state, but that all federal territory north and west of the state would ban slavery. Maine also came into the Union as a free state. Most protections for enslaved people outlined in the Code Noir, such as protecting them from enslavers’ abuse or the breaking up of families at the auction block, were disregarded as Missouri became a state.

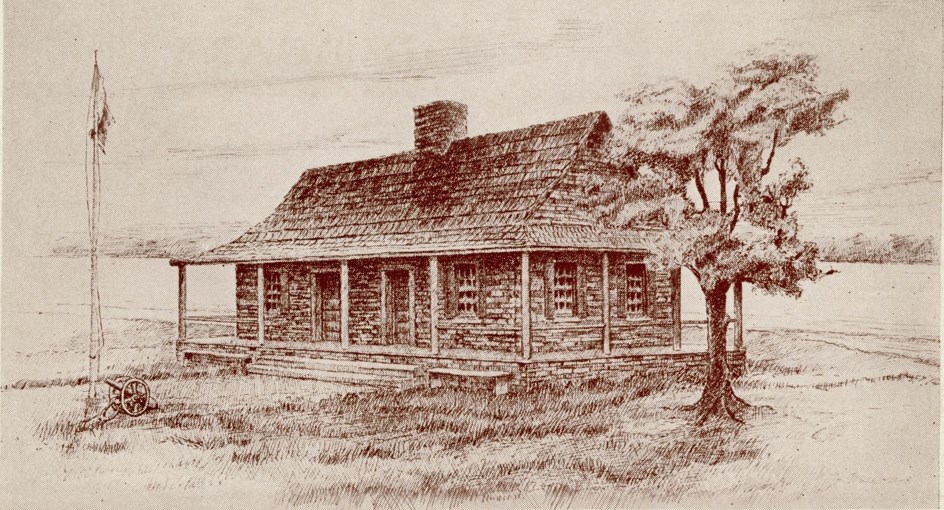

Missouri Historical Society

St. Louis's colonial headquarters building was at the intersection of Main and Walnut streets. Built in 1768, French and Spanish officials working at this building made sure the Code Noir was enforced in St. Louis.

Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Previous: A Society Built Upon Enslaved Labor

Next: Slavery and the Law

Last updated: November 2, 2023