Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Article

The Civil War and Emancipation in St. Louis

Library of Congress, colorized by Nick Sacco/History Beyond Black and White

Claiming Citizenship and Freedom

When the American Civil War broke out in April 1861, the U.S. army quickly mobilized to control St. Louis. Martial law (military rule) was soon established. Under this rule, anyone suspected of supporting the Confederacy faced potential arrest, trial, and imprisonment. Enslaved people took advantage of these circumstances to claim freedom for themselves and their families. Enslaved women often reported disloyal enslavers to the army, thereby showing their support for the Union. Although Black men would not have the chance to fight for the U.S. military until 1863, they often went to military camps to offer their services. Enslaved men cooked, cleaned, served as caretakers, and worked a range of other jobs in the camps. Enslaved women and children were occasionally welcomed into the camps as well.

In using the U.S. military to claim freedom and citizenship, enslaved people in St. Louis demonstrated their understanding of the Civil War as a conflict over the fate of slavery and their willingness to support the Union war effort.

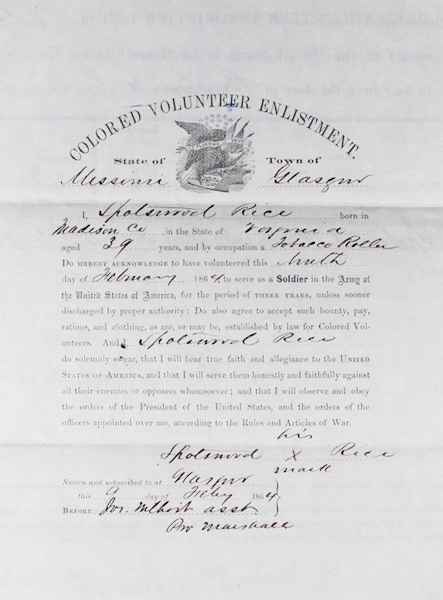

National Archives and Records Administration

Slavery and Freedom in St. Louis - Spottswood Rice

Spottswood Rice (1819–1907) was born enslaved in Virginia and raised in Howard County, Missouri. When the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, Rice offered his services to the 67th USCT regiment near Kansas City. In the fall of 1864, Rice was sent to the hospital at Benton Barracks to recover from rheumatism.

Kitty Diggs, a White enslaver in Howard County, Missouri, held Rice’s wife and children in bondage. In a powerful letter to Diggs, Rice wrote from St. Louis that he intended to free his daughters Mary and Cora “if it cost me my life.” Diggs had previously claimed that Rice wanted to “steal” his children from her. In response, Rice stated that “she is the first Christian that I ever heard say that a man could steal his own children, especially out of human bondage.” He also warned Diggs that a force of 1,600 White and Black soldiers would come to her plantation to rescue the children.

While Rice’s vision of a military attack on the Diggs plantation never occurred, Mary and Cora were eventually reunited with their family. The two daughters were listed on the 1880 census as living with their parents in St. Louis, where Rice became a minister of the African Methodist Church.

Did the Emancipation Proclamation Apply to Missouri?

No. President Lincoln’s order freeing enslaved people only applied to Confederate states that were in active rebellion against the United States. Missouri remained in the Union and was therefore exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation. However, slavery was effectively destroyed as the fighting continued. Enslaved people understood the implications of the Emancipation Proclamation, even if they lived in a state where it didn’t apply. For example, First Lady Julia Dent Grant later recalled that all the enslaved people at her father’s White Haven home simply left the property by early 1864, perhaps emboldened by the Emancipation Proclamation. On January 11, 1865, a state constitutional convention abolished slavery in Missouri. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery nationwide in December of that year.

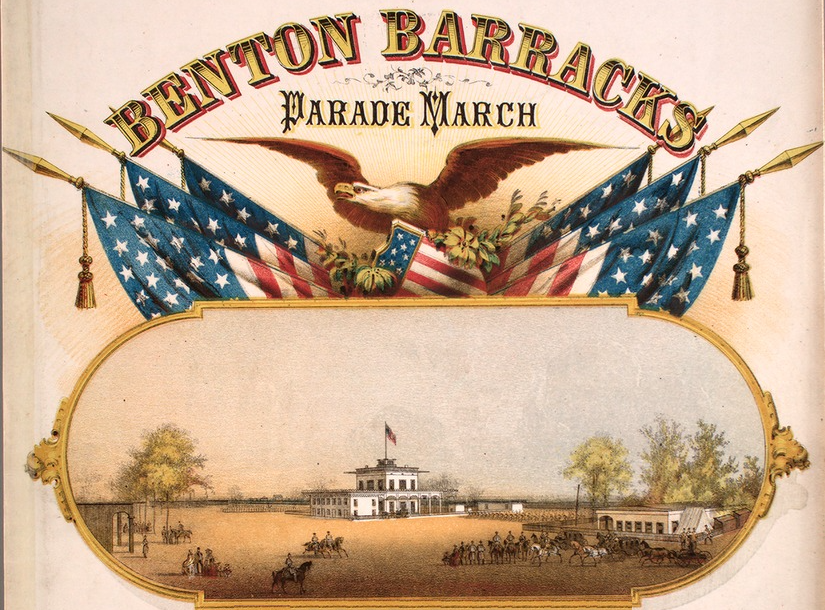

Public Domain/Wikipedia

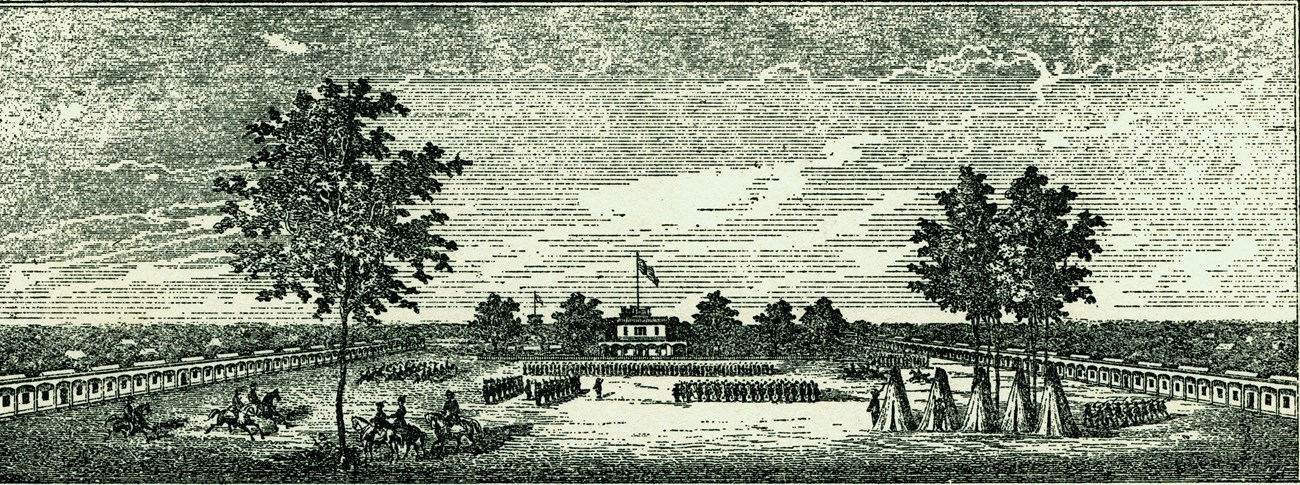

United States Colored Troops and Benton Barracks

When President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, it opened a door for Black men to serve as soldiers in the U.S. military. Roughly 3,700 Black men from Missouri, most of whom were enslaved, served in United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments during the war.

The largest military base in St. Louis was Benton Barracks. It was located where Fairgrounds Park is today in North St. Louis. The base served as a training ground for new soldiers, a hospital for wounded soldiers, and a warehouse for food and supplies. During 1863 and 1864, four USCT regiments were organized at Benton Barracks. The 62nd, 65th, 67th, and 68th USCT regiments all received their basic training at the base and served with distinction for the remainder of the war.

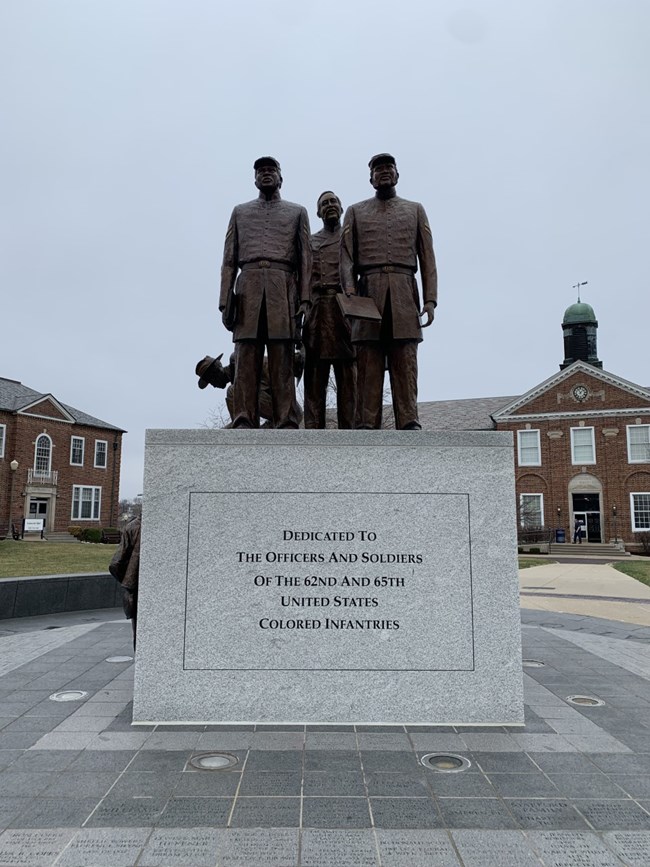

NPS/Nick Sacco

The troops in the 62nd and 65th USCT regiments helped to promote education for Black children in Missouri after the war. While learning how to read and write themselves, these soldiers pooled the money they earned as soldiers to help establish a school. These efforts led to the establishment of Lincoln Institute (now Lincoln University) in Jefferson City in 1866. This school became the first institute of higher education for Black students in Missouri.

Today, a statue on campus honors those USCT troops.

Missouri Historical Society

A lithograph drawing of Benton Barracks during the Civil War.

Last updated: November 2, 2023