Part of a series of articles titled French Language and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Article

The Chain of Communication

Written by Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Digital Intern, Katie Ridder.

This article is one in a series, French Language and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Lewis and Clark Trail Digital Interns.

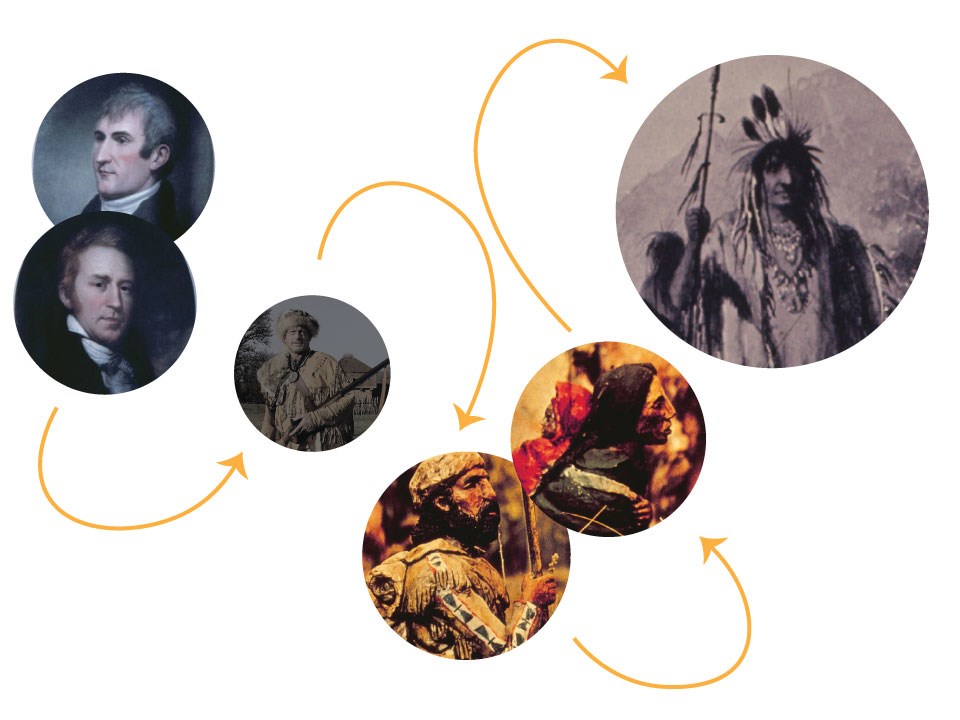

Communication on the Lewis and Clark Expedition required a complex chain of translation that at times consisted of five or more people. Each person involved in these translations was vital, especially as there were times when the expedition relied on the aid or goodwill of the Native Americans with whom they were speaking in order to continue with their journey. The large number of languages and people involved in this process meant that simple introductions and an explanation of the expedition’s purpose could take hours, much less any trade of goods or information (Vinikas).

Neither Lewis nor Clark spoke languages other than English, and so they were reliant on the members of their expedition who did in order to communicate with the Native peoples. It is possible that, as a result, some of the intentions and nuances that accompanied their phrasing was not translated along with the words. For example, both men addressed the Native Americans that they spoke with as “Children”, though those Native Americans were adults and often leaders in their own right. This way of referring to the people they encountered has a patronizing tone that may not have been conveyed through the multiple languages necessary for conversation (Vinikas).

Following English, the next language in the chain of translation was usually French. Though some members of the expedition, such as French Shawnee tracker George Drouillard, also spoke some Native American languages or sign language. This sign language was a common language that allowed communication between differing peoples and communities. There are some regional variations of this sign language, but ultimately it facilitated interactions between peoples with separate spoken languages (Davis). At times, using this sign language, members of the expedition were able to communicate directly to the people, however, that was not usually the case (Skarsten). So, the captains would speak English to one of the French-speaking members of the expedition, often Drouillard or Francois Labiche, a French Omaha trader from Fort Kaskaskia among a few others (Francois). Depending on the Tribe they were engaging these men would then relay the message in French to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader who was brought along on the expedition primarily for his valuable place in this chain of communication (Toussaint).

After being told Lewis or Clark’s words in French from one of the other men, Charbonneau would translate them into Hidatsa for his wife, Sacagawea. She was Lemhi Shoshone, and the expedition’s trade with her people during the journey proved to be invaluable. This was especially true when the expedition bargained with the Shoshones for horses (Francois). After listening to her husband’s Hidatsa, she would speak to the Shoshones in her native Shoshone. Once they had replied to her, she would relay that message back to Charbonneau and the words would travel back down the chain of translation in the other direction. This tedious process would continue until an agreement had been reached.

At one point in the expedition, the chain of communication stretched even farther, adding yet one more person, and the language needed to speak to them. While traveling with their Shoshone guide over the mountains in late 1805, the party met the Salish, or Flatheads, people with whom their guide was able to communicate. These people were called Flatheads despite the fact that they did not practice the flattening of children’s skulls as was common to other Columbia River tribes. So, after Sacagawea spoke to their guide in Shoshone, he would speak to the Salish and receive a reply to pass back (Francois).

Despite the complicated nature of this chain of translation, and the number of hours required for the most basic of conversations, it was clearly successful. In their journals both Lewis and Clark praised the valuable skills of their translators and referred to the vital goods and information obtained from their interactions with various Tribal Nations. The fact that these translators were able to successfully make their intentions known, ask questions, and even conduct trade across not only the many languages needed to speak between themselves, but the numerous dialects of the peoples they encountered was truly impressive (Vinikas). Without the knowledge and input of each person involved in this lengthy chain of translation, it is possible that the expedition would have failed to reach its goal.

NPS Graphic with public domain images from NPGallery

Sources

- Vinikas, Vincent. The Historian, vol. 67, no. 1, Wiley, 2005, pp. 127–28, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24452899.

- Davis, J. (2017). Native American signed languages. Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.013.42

- Skarsten, M. O. George Drouillard: Hunter and Interpreter for Lewis and Clark and Fur Trader, 1807-1810. University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

- “Francois Labiche.” Discovering Lewis and Clark, Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/2572.

- “Toussaint Charbonneau.” Discovering Lewis and Clark, Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/2664.

- U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). Salish. National Parks Service. Retrieved January 31, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/jeff/learn/historyculture/salish.htm

Last updated: April 17, 2023