Part of a series of articles titled Drive the Enemy South.

Previous: Battle of Fisher's Hill

Next: Battle of Tom's Brook

Article

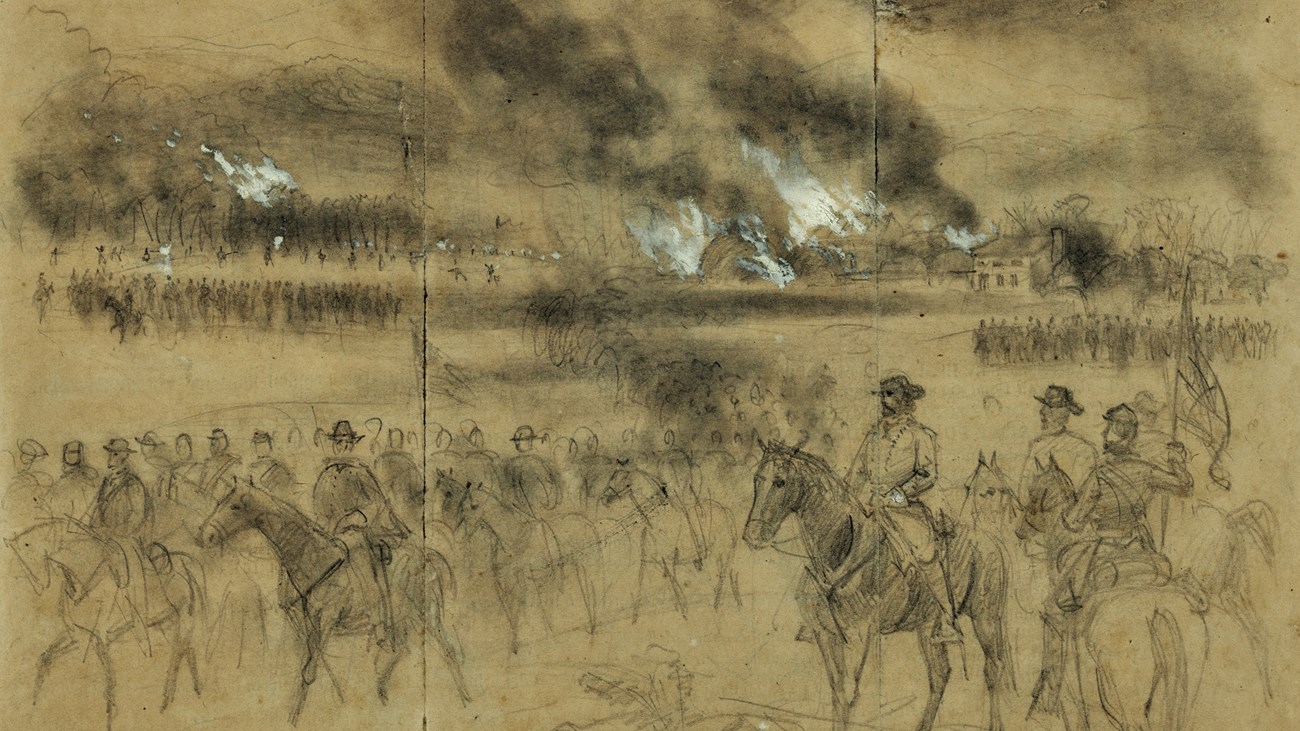

Library of Congress

"What is the worst in war, to burn a barn or kill a fellow man?"

Confederate Cavalry Officer

The Shenandoah Valley became a prime target in 1864 as the American Civil War took a turn toward "hard war." "The Burning," as it came to be called, was part of a Federal strategy to hasten the end the of the war.

When Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant became general-in-chief of the Federal Army in March 1864, he and President Lincoln permitted the army to take or destroy of civilian property deemed useful to the Confederate war effort. They wanted not only to destroy supplies, livestock, and food meant for Confederate armies, but also to erode the Southern people’s support for secession.

Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, who carried out this strategy in Shenandoah Valley, said,

"Those who rest at home in peace and plenty see but little of the horrors… [of war] and even grow indifferent to them as the struggle goes on, contenting themselves with encouraging all who are able-bodied to enlist in the cause… It is another matter, however, when deprivation and suffering are brought to their own doors. Then the case appears much graver, for the loss of property weights heavy with the most of mankind; heavier often, than the sacrifices made on the field of battle. Death is popularly considered the maximum of punishment in war, but it is not; reduction to poverty brings prayers for peace more surely and more quickly then does the destruction of human life…"

After Lt. Gen. Jubal Early's raid on Washington in mid-July, Grant advised his chief of staff Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck to see to it that Early was pursued by "veterans, militia men, men on horseback, and everything that can be got to follow," with specific instructions to "eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them."

When Sheridan took command of the Army of the Shenandoah on August 6, Grant's ordered him to,

"Give the enemy no rest… Do all the damage to railroads and crops you can. Carry off stock of all descriptions, and negroes, so as to prevent further planting. If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste."

Sheridan’s orders had three objectives: disable the Valley's use as an avenue for invasion, destroy the Confederacy’s breadbasket, and break the Southern will to fight.

Sheridan began destroying the lower Valley. On August 17 he reported, "I have burned all wheat and hay, and brought off all stock, sheep, cattle, horses, &c, south of Winchester." After his successes at the battles of Third Winchester and Fisher's Hill, Sheridan followed Early south of Harrisonburg. Sheridan's cavalry raided as far south as Staunton and Waynesboro.

Grant wanted Sheridan to follow the rail lines east and destroy Gen. Lee's supply lines as he went. Sheridan felt that the Federals would not be able to cross the Blue Ridge easily and that this route would stretch his supply lines too thin. He also believed that Early still threatened the Valley. Sheridan suggested a different plan, writing:

"My judgment is that it would be best to terminate this campaign by the destruction of the crops, &c., in this valley, and the transfer of troops to the army operating against Richmond."

Grant responded,

"You may take up such position in the Valley as you think can and ought to be held, and send all the force not required for this immediately here. Leave nothing for the subsistence of an army on any ground you abandon to the enemy."

Sheridan commenced a dramatic war on the countryside on September 26,1864 that would last for thirteen days. The destruction would begin in Staunton and head down the Valley, northward to Strasburg, covering a length of 70 miles and a width of 30 miles. This destruction infamously became known for generations simply as "The Burning." Sheridan ordered his men to move fast, destroy everything that could be useful to the enemy, then move on quickly to new targets. He also instructed them to spare houses, empty barns, property of widows, single women, orphans and to refrain from looting. Col. James H. Kidd of Custer's brigade described the scenes as they set fire to a mill in Port Republic:

"What I saw there is burned into my memory. The anguish pictured in their faces would have melted any heart not seared by the horrors and 'necessities' of war. It was too much for me and at the first moment that duty would permit I hurried from the scene."

Regardless of personal feelings about the suffering of civilians, there was an element of revenge in the campaign. Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt described the area as a "…paradise of bushwhackers and guerrillas. Officers and men had been murdered in cold blood on the roads while proceeding without a guard through an apparently peaceful country."

The most notable death was of Sheridan's engineer officer Lt. John R. Meigs, killed near Dayton by Confederate scouts. In retaliation, Sheridan ordered "all houses within an area of five miles burned." Lt. Col. Thomas F. Wildes, concerned about the order of retaliation on the towns people encouraged Sheridan to reconsider order to burn the town. After some thought, Sheridan withdrew the order to burn Dayton.

Flames destroyed much of the hard labor of Valley civilians. The fear of potentially losing everything inflicted a psychological hardship on these people. The weakened Confederates could do little to stop the destruction. One Southern soldier later recalled:

"We had an elevated position and could see the Yankees out in the valley driving off the horses, cattle, sheep and killing the hogs and burning all the barns and shocks of corn and wheat in the fields and destroying everything that could feed or shelter man or beast…"

On October 7, Sheridan reported to Grant:

"I have destroyed over 2,000 barns filled with wheat, hay and farming implements; over 70 mills, filled with flour and wheat; have driven in front of the army over 4,000 head of stock, and have killed and issued to the troops not less than 3,000 sheep."

While the agricultural devastation was important, Sheridan also assessed the psychological impact on the residents: "The people here are getting sick of war." Sheridan had successfully made the Valley "untenable for a Rebel Army." The Burning was not the last instance of hard war. That winter and following spring, the U.S. Army burned its way through Georgia and South Carolina.

Part of a series of articles titled Drive the Enemy South.

Previous: Battle of Fisher's Hill

Next: Battle of Tom's Brook

Last updated: January 30, 2023