Last updated: January 29, 2021

Article

The 1957 Crisis at Central High

Little Rock Central High School NHS

September 2-4, 1957

Under a federal court order, the Little Rock School District prepared to admit African American students to Central High School. On the evening of September 2, 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus announced in a televised speech his intention to use Arkansas National Guard troops to “prevent violence” and prohibit the students from entering the school. On September 4, ten African American students attempted to enter the school, but were turned away by the troops. Much of the press coverage that day focused on 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford, who found herself alone in the midst of the crowd.

“I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the mob—someone who maybe would help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me.”

Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Little Rock Nine

All of the African American students were denied entry to the school for the next two weeks.

September 5-23, 1957

None of the ten African American students attempted to attend school on September 5, 1957. That same day, the school board requested a suspension of its desegregation plan, but this request was denied by Federal District Judge Ronald Davies two days later.

"The only assurance I can give you is that the federal constitution will be upheld by me by every legal means at my command.”

President Eisenhower in telegram to Governor Faubus.

On September 14, Governor Faubus met with President Dwight Eisenhower in an attempt to resolve the situation. Six days later, on September 20, Judge Davies rules that Faubus has not used the Arkansas National Guard troops to preserve the law and orders them removed.

One of the ten students saw an end to her opportunity to attend Central. Jane Hill's family received death threats and her father was told that he would lose his job if Jane attempted to attend Central High. She was instructed by her father that she would not be attending Central and returned to Horace Mann High School

With the guard withdrawn, the Little Rock police tried to maintain order as the eight of the African American students finally entered Central High School. Television viewers nationwide watched as rioting broke out. The police lost control of the crowd and the students had to be smuggled out of the back of the school for their safety.

“They’ve gone in…Oh, God, [they] are in the school.”

Anonymous man in the crowd in front of Central.

“That was the first time I’d ever gone to school with a Negro, and it didn’t hurt a bit.”

Robin Woods, student at Central High School.

September 24-25 1957

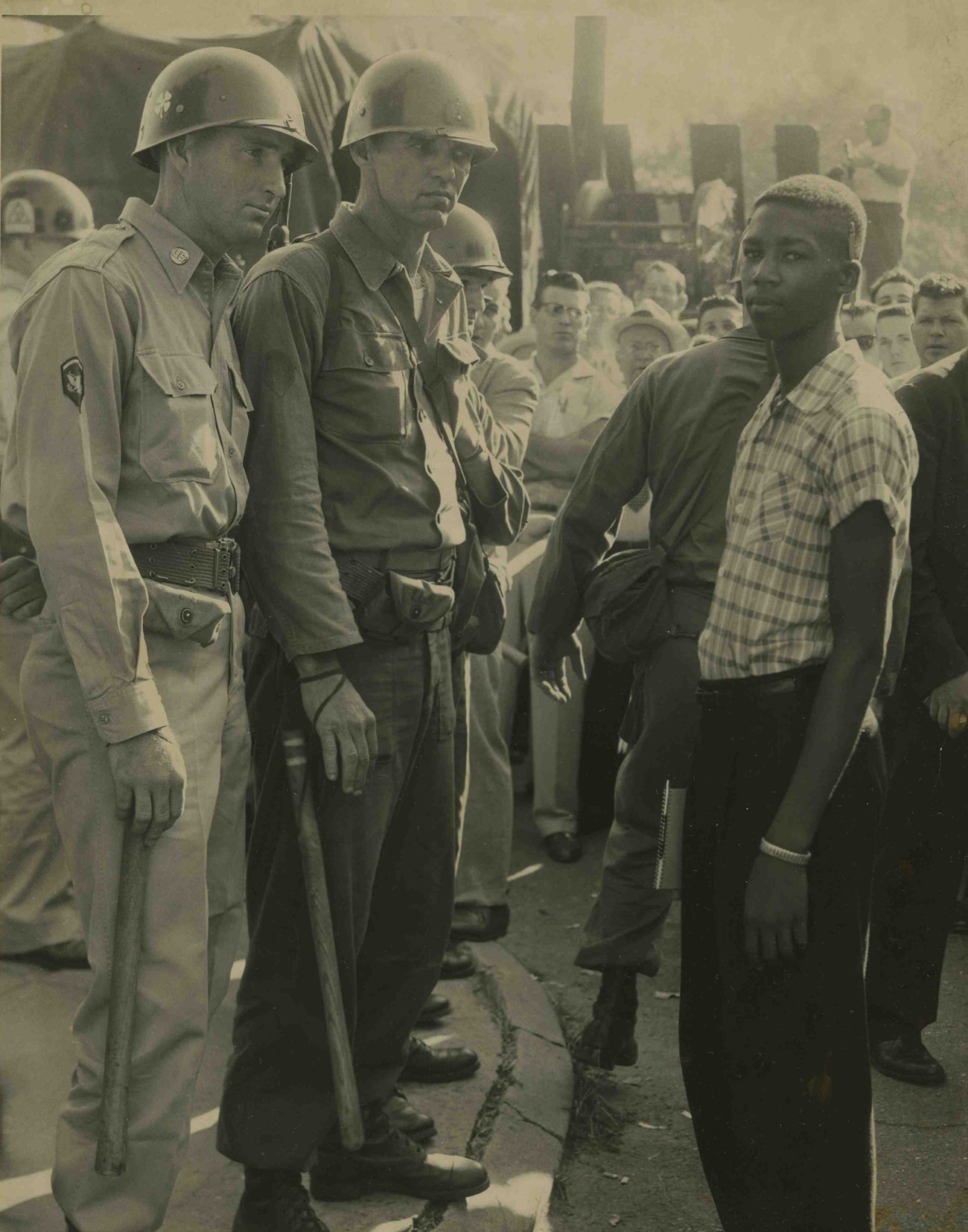

Calling the rioting “disgraceful,” President Eisenhower orders units of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock and federalizes the Arkansas National Guard.

“We are now an occupied territory. Evidence of the naked force of the federal government is here apparent in these unsheathed bayonets in the backs of schoolgirls…”

Governor Orval Faubus

On September 25, under federal troop escort, nine African American students, dubbed the "Little Rock Nine" by the media, enter Central High School for their first full day of classes.

“Any time it takes 11,500 soldiers to assure nine Negro children their constitutional rights in a democratic society, I can’t be happy.”

Daisy Bates, President, State Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

“If parents would just go home and let us alone, we’ll be all right…We just want them to leave us be. We can do it.”

Anonymous 16 year old white female student at Central High

September 1957 - April 1958

The federal troop presence remained throughout the school year at Central. Inside the school, The Little Rock Nine fell off of the media’s radar screen and into no man’s land. Student leaders pledged to obey the law and asked their fellow students to do the same. In spite of this, a group of white students verbally and physically harassed the Nine during the year.

“After three full days inside Central, I know that integration is a much bigger word than I thought.”

Melba Pattillo, one of the Little Rock Nine

Amid the continued abuse, one of the Little Rock Nine, Minnijean Brown, fought back and was ultimately expelled from Central in February 1958. She moved to New York and lived with Drs. Kenneth B. and Mamie Clark, directors of the Northside Center for Child Development. She graduated from New Lincoln High School in 1959.

May 1958

“It’s been an interesting year. I’ve had a course in human relations first hand.”

Ernest Green, one of the Little Rock Nine

On May 25, 1958, Ernest Green, the only senior among the Little Rock Nine, became the first African American graduate of Central High School. By the end of the 1957-58 school year, the Little Rock Nine had earned the right to be called Central High students.