Last updated: March 12, 2021

Article

The 1879 “Government Shutdown,” Part II

Library of Congress

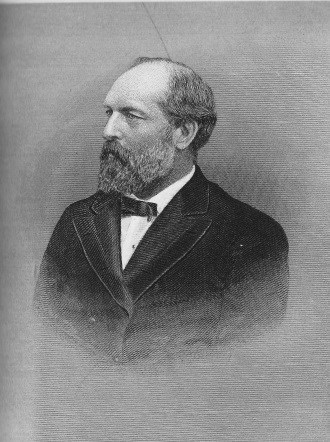

Congressman James Garfield augmented Hayes’ constitutional scruples with a defense of black voting rights. He decried the Democrats’ attempt to achieve “wholesale disfranchisement of the Negro…in the South” as an attack on his party’s legacy: the ending of slavery, Constitutional amendments guaranteeing citizenship and voting rights to blacks, and the supremacy of the Union. These Republican constitutional arguments at the same time served the party for partisan political advantage.

The idea that what the Democrats were up to was an attempt to undermine the Constitution was seen as “revolutionary” by Hayes, by Garfield, and by other prominent Republicans. Plain and simple, the Democrats were trying to blackmail Hayes into ending federal voting rights provisions in the states.

Library of Congress

In a speech before the House, later published as “Revolution in Congress,” Garfield pointedly remarked, “… if the President, in the discharge of his duty, shall exercise his plain constitutional right to refuse his consent to this proposed legislation, the Congress will so use its voluntary powers as to destroy the government. This is the proposition… we confront; and we denounce it as revolution.”

Even two of President Hayes’s Republican detractors came to his defense. New York Senator Roscoe Conkling stood before the Senate on March 24, 1879, and excoriated the Democrats demand that unless “another species of legislation [a rider] is agreed to, the money of the people… shall not be used to maintain the government.” This, he said, was “revolutionary…” Conkling’s arch rival, Maine Senator James G. Blaine, agreed. “I call it the audacity of revolution for any senator or representative… to get together and say [to the President and the country], ‘We will have this legislation or we will stop… the government.’ That is revolutionary…”

Over the course of three months, the Democrats tried five times to attach riders to appropriations bills for the Army and for the Legislative, Executive and Judicial branches of the government. All had the same object: rid the South of federal marshals and end the Army’s presence at the polls.

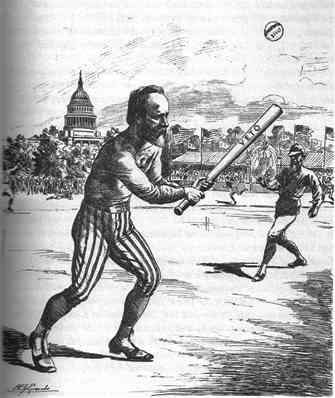

Hayes vetoed every bill with such riders. Each time, his veto was sustained in the House because Republicans, guided by Congressman Garfield, stood firmly against the Democrats.

Daily Graphic

Hayes and Garfield stood shoulder to shoulder against Democratic maneuvers to weaken the protections of citizens at the polls. Hayes’ insistence that he would not be bullied by the Democrats was so determined that Congressman Garfield feared that the President’s strategy would backfire. He appealed to Hayes to find some face-saving compromise to save the Democrats total embarrassment. The President scoffed at Garfield’s chivalrous concern: ‘A square backing down is their best way out, and for my part I will await that result with complacency.”

The self-confident Hayes insisted that he would not sign any appropriations bills with the riders to which he objected. Only once did Hayes approve an appropriation bill with riders. It funded the Army and the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches, but omitted funding for federal marshals. In the end, the Democrats were able to withhold only $600,000 of the $45,000,000 needed to keep the federal government functioning.

In the end, Hayes, Garfield and their Republican colleagues successfully defended the President’s constitutionally mandated veto power. In this, they had taken a step in reinvigorating the role of the president in national affairs.

The success of the political goal of defending black voting rights and of increasing Republican influence in the South was not as obvious. After all, the Democrats had won a partial victory. They were able to defund the marshals. However, as the marshals were called to duty only at election time, there was still time for the President and Congressman Garfield to get them funded. A deficiency bill to provide funding not approved earlier is mentioned in the diaries of both Hayes and Garfield in April 1880.

Library of Congress

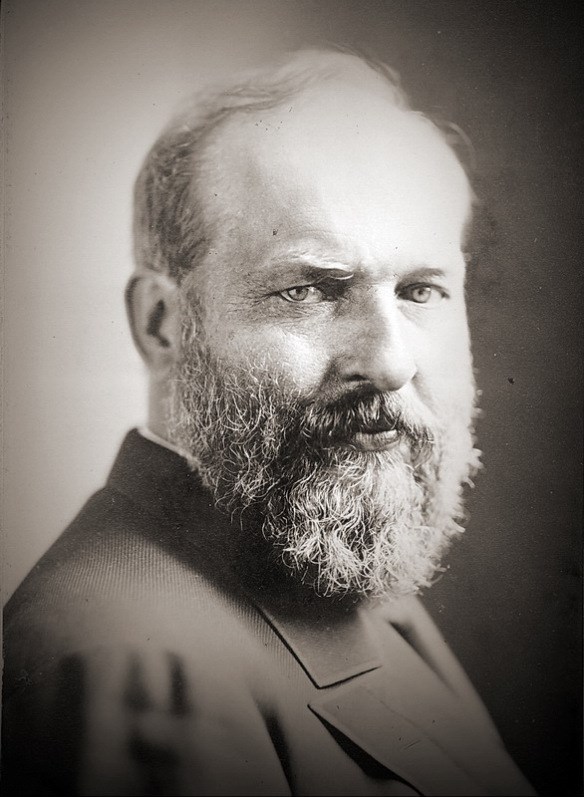

Over the course of three months, Hayes’ battle with the Democrats won him respect in many parts of the country, and especially among Republicans. “I am now experiencing one of the ‘ups’ of political life,” he wrote on July 3. "Congress adjourned on the 1st after a session of almost 75 days mainly taken up with a contest against me. Five vetoes, a number of special messages and oral consultations with friends and opponents have been my part of it. At no time… has the stream of commendation run so full. The great newspapers and the little have been equally profuse of flatter…”

Garfield emerged as the leading spokesman for the administration. Already, in early 1879, there was talk among prominent Republicans that Garfield should be a candidate for president.

A constitutional victory for the Executive was won in 1879 that could not be diminished: a president could not – or should not – be forced to sign legislation with which he disagreed.

First, the tensions between the Executive branch and the Legislative branch of the government were illuminated. In 1879, the Executive branch, which had been weakened in relation to Congress after the death of Lincoln, was strengthened by President Hayes’s determined stand. His Republican allies in Congress, united by the leadership of Congressman Garfield, gave Hayes critical support.

Second, the 1879 controversy was indeed “revolutionary,” as Republicans claimed. At no time before had there been such a bold attempt to “shut down” the operations of the federal government by a denial of funding. At no time after, until a partial shutdown caused by the Democrats in 1976 when Gerald Ford was President, was such a tactic employed again. The threat of shutdowns has occurred with greater frequency in the last forty years, making our own politics “revolutionary” in nature.

Finally, as is often true of modern politics, the 1879 veto fight contained a measure of temporary political advantage for both political parties. However, both parties were divided internally and neither could be assured of easy victory as they approached the 1880 presidential campaign. Meanwhile, African-Americans, whose political status was at the center of the 1879 controversy, steadily lost ground in their fight for respect and civil rights, another legacy of the divisive politics of the Hayes/Garfield era.

Written by Joan Kapsch and Alan Gephardt, Park Rangers, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, November 2016 for the Garfield Observer.