Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

The 1879 “Government Shutdown,” Part I

PBS

Library of Congress

In recent years, Americans have become accustomed to threats of a “government shutdown” at the hands of one party in the Congress, opposed to the programs and policies of the President of the opposite party. One side cries, “Politics!” The other side counters, “Principle!” But when threatening to defund the government in order to change public policy was first attempted in 1879, the cry was “Revolution!” Politics and principle, principle and politics vied with one another in minds, and hearts, and maneuvers, of all parties involved.

Some background is in order. Between 1865 and 1870, the years immediately following the Civil War, the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution were adopted. These were the first amendments to the Constitution to be passed in sixty years. The amendments abolished slavery in the United States, conferred citizenship to the newly freed people, and granted black males the right to vote. With these amendments came modern conceptions of civil rights and voting rights.

Newberry Library

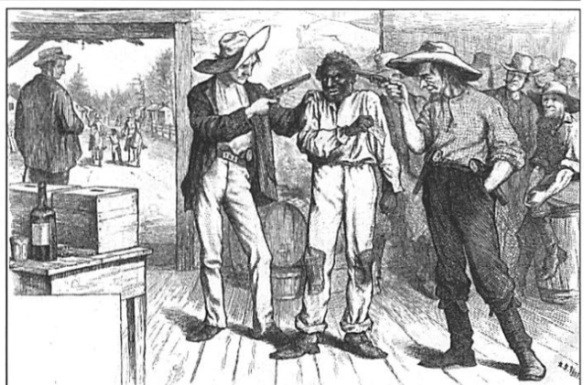

Through several legislative measures in the late 1860s and 1870s, blacks gained property rights and equal protection under the law. Mechanisms to ensure that blacks could vote in free and fair elections were established, supported by the U.S. Army and federal courts.

At the same time, many white southerners were disfranchised. Immediately after the Civil War, former political and military leaders of the Confederacy were barred from holding political office. Many white southerners felt that they were at the mercy of Republican Carpetbaggers from the North, the Union Army, and the newly freed blacks, who for the first time exercised political power in state legislatures and in the U.S. Congress.

The once-dominant southern Democrats were determined to regain their political and social dominance in the former Confederacy. For more than a decade they used intimidation, physical violence, and even murder to keep blacks and southern Republicans from the polls.

Library of Congress

Federally appointed civilian officers were employed to monitor the fairness of elections. When violence broke out, the U.S. Army was brought into maintain peace and an orderly election process.

Fearing “negro domination,” white southern Democrats invoked states’ rights. Republicans sought to preserve the rights of the freedmen as a matter of justice, and also as a means to expand the influence of their party in the South. These constant tensions were at the heart of the controversy in 1879.

In early 1879, in the waning days of the second session of the 45th Congress, the House’s Democratic majority attached riders to funding bills to prohibit the use of federally appointed marshals to oversee elections, and to prevent the Army from having any role in protecting voters at polling places. The Republican Senate would not agree to these measures. As a result, Congress failed to pass $45,000,000 in appropriations for the Federal government for the fiscal year beginning on July 1.

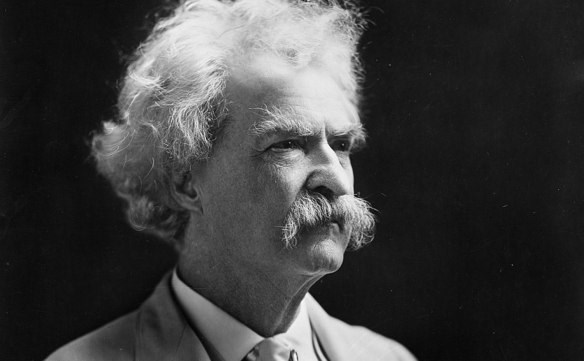

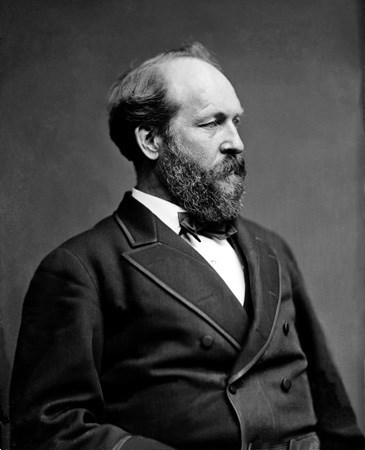

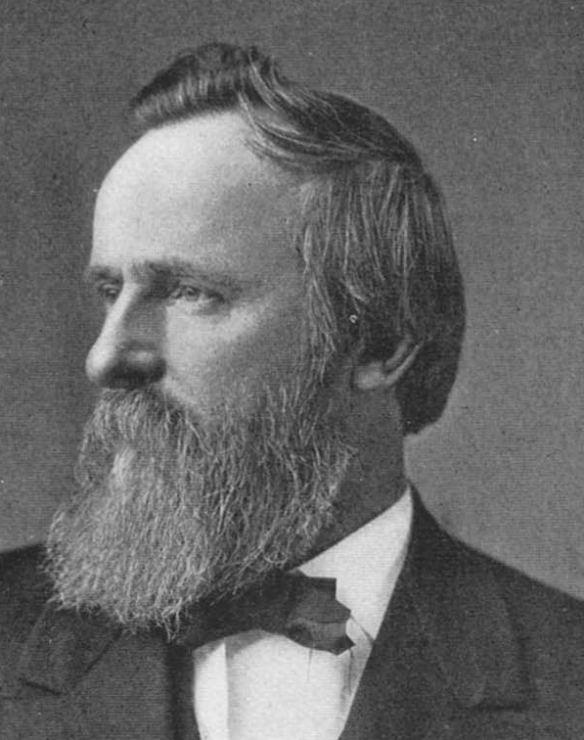

This impasse caused President Hayes to call the 46th Congress into special session on March 18. The new Congress presented a problem for the Republican president. Both the Senate and the House were now controlled by the Democrats (for the first time since 1859). This spelled trouble for Hayes and his chief lieutenant in the House of Representatives, James Garfield.

Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center

Toward the end of April, the 46th Congress passed an Army Appropriations bill with a rider identical to the one that passed at the end of the 45th Congress. Once again, the Democrats aimed at preventing federal marshals to oversee elections. Once again, the Army would be prohibited from keeping peace at the polls during congressional and presidential elections.

From the Democrats’ point of view, it was time to end Republican and federal government interference in elections in southern states. They invoked the constitutional principle of states’ rights while they sought to insure the dominance of white men in the politics of their states. They were also looking to the 1880 presidential contest, hoping to be able to intimidate or discourage enough black voters to elect a Democrat president for the first time since 1856.

Using the appropriations authority vested in the House of Representatives, the Democratic majority was trying to force the hand of the Republican president – to sign the appropriation with the objectionable rider – or to defund the government. Senate Democrats were in full accord with their House colleagues.

President Hayes and Congressman Garfield understood both the constitutional argument being made by the Democrats and the political advantage they sought. Even before the final bill was passed, Hayes wrote in his diary, “The appropriation bill is essential to the continuance of the Government… It is the duty of Congress to pass it. The rider is attached to get rid of the Constitutional exercise of the veto power to defeat… [a rider]… the Pres[iden]t does not approve…” The political gamesmanship of the House Democrats gave the Republican President a constitutional argument with which to battle them.

In his diary, the president expressed his thoughts about this controversy many times. Of the Democrats he wrote, “They will stop the wheels – block the wheels of government if I do not yield my convictions in favor of the election laws. It will be a severe, perhaps a long contest. I do not fear it – I do not even dread it. The people will not allow this Revolutionary course to triumph.” Later, he confided, “I object to the [army appropriations] bill because it is an unconstitutional and revolutionary attempt to deprive the Executive of one of his most important prerogatives… [and to] coerce him to approve a measure which he in fact does not approve.” This was the constitutional counter-argument taken up by the Republicans.

(Check back soon for Part II!)

Written by Joan Kapsch and Alan Gephardt, Park Rangers, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, October 2016 for the Garfield Observer.