Part of a series of articles titled The Military History of Fort Schuyler.

Article

The 1777 Siege of Fort Schuyler

National Park Service

The siege of the fort began officially on August 3, 1777 when the British sent their first surrender demands to the fort, and would continue through the next 21 days. An advanced party of the British force had arrived on August 2, in an attempt to intercept supplies heading for the fort. This advance party was unsuccessful, and the supplies got safely into the fort. The British force was made up of approximately 800 British, German, loyalist, and Canadian troops and around 700-1,000 British allied Indians. They were under the command of Lt. Col. Barry St. Leger, who had been made a Brevet (temporary) Brigadier General for this campaign. Inside the fort were the Third New York Regiment and two detachments of Massachusetts troops. Together, they totaled around 750-800 men, all under the command of Col. Peter Gansevoort of the 3rd NY. The British eventually established their camps about a mile to the northeast of the fort. The loyalists and Indians established their main camps to the south and east of the fort, between the two landings on the Mohawk River.

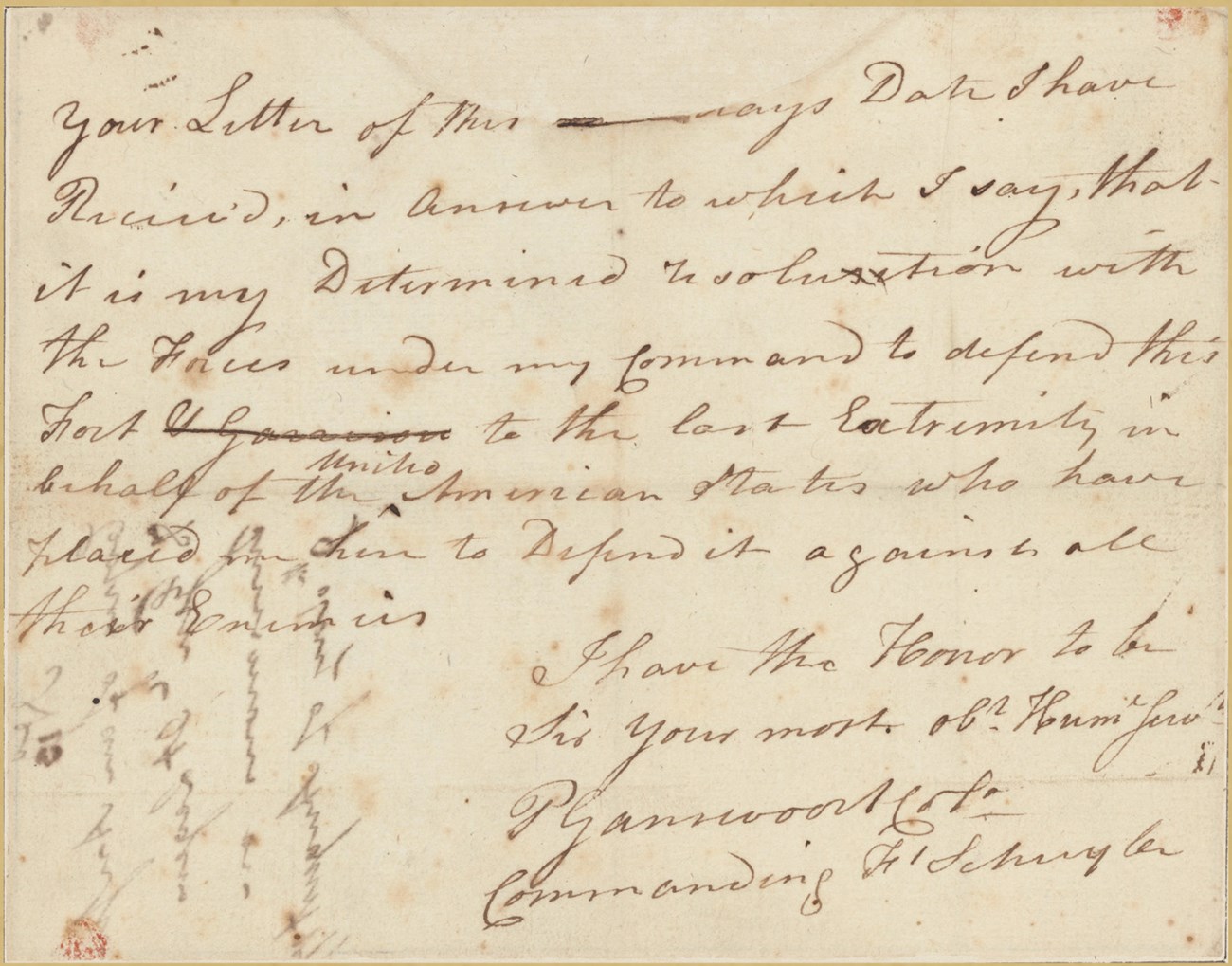

On the morning of August 3, the garrison raised a hand-made flag up the flagpole and fired a saluting round towards the British camp. In the afternoon a summons to surrender was delivered to the garrison. In the words of Ensign Colbrath of the 3rd NY, the summons "was rejected with disdain." For the first few days of the siege, St. Leger could only bring musket and rifle fire against the fort, because his artillery was stuck on his boats on Wood Creek. The Tryon County Militia had blocked the creek by felling trees into its entire length. Both sides also sent parties out to gather hay from the fields around the fort, and to burn buildings that blocked lines of fire or could provide cover to an enemy.

Manuscripts and Archives, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

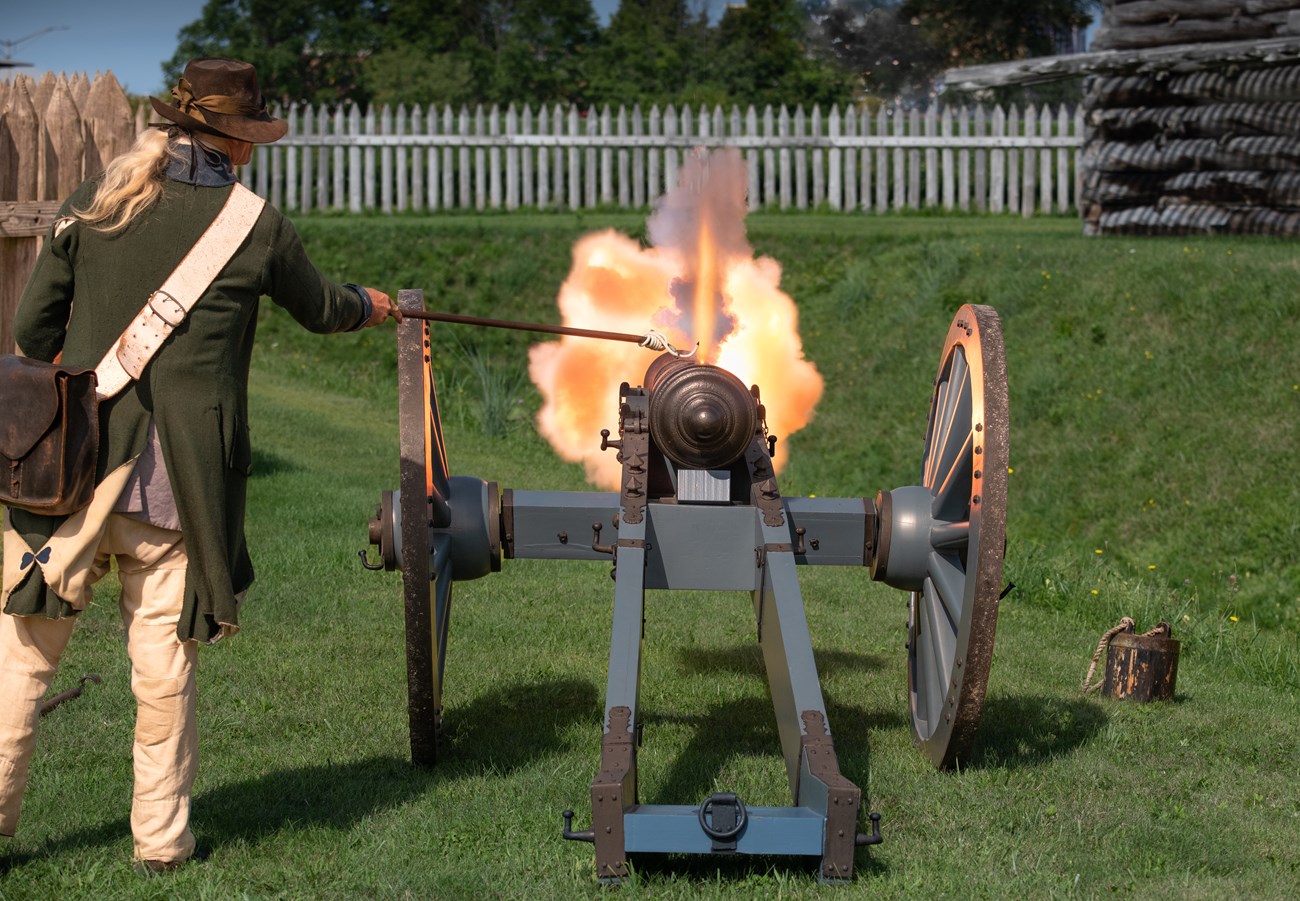

On the morning of August 6, three militiamen made their way through the British siege lines to let Col. Gansevoort know that Gen. Nicholas Herkimer was coming to aid the fort with 800 of the local Tryon County Militia. In order to create a diversion that would help Herkimer get through to the fort, Lt. Col. Marinus Willett (second in command of the 3rd NY) was ordered to make a sortie against the enemy's camp. With 250 men (half NY, half MA) and a 3-pound gun, Willett charged out of the main gate and struck the Indian and loyalist camps by the Mohawk River. The camp guards were completely routed and fled towards the main British camp, leaving Willett's force in control of the two camps, which were immediately plundered and destroyed. Meanwhile, St. Leger had thrown together what troops he could, and moved to intercept Willett on his return to the fort. Before St. Leger's troops were fully formed to attack however, they came under fire from Willett's three pound gun. This, coupled with the cannon fire from the fort, broke up the British formations and allowed Willett's force to get back inside the fort "without the loss of a single man." Willett's force captured a large amount of equipment, papers, and personal belongings from the enemy's camp. From prisoners taken during the sortie, the garrison learned Herkimer' force had been ambushed by St. Leger's Indians near the Indian village of Oriska and had been forced to retreat.

National Park Service/Dan U.

Finding that their artillery was having little effect on the fort and garrison, the British turned to other means to force the fort to surrender. On August 11, the British diverted the stream that ran past the east wall of the fort, in an attempt to deprive the garrison main water supply. There was already one well within the fort however, and the men were able to dig two more, which provided them with enough water. On August 19, the British began digging saps and parallels (zigzag trenches) towards the northwest bastion of the fort.

It was probably through the deserters from the fort that St. Leger had learned that the fort's powder magazine was located in the northwest bombproof. His plan was to push trenches towards that bombproof that would allow his small mortars to be used as howitzers, throwing explosive shot directly at the walls of the fort. These trenches would allow his troops to move up and begin undermining the bastion. An explosive charge would then be placed to blow the bastion and the powder magazine apart. Despite the heavy fire coming from the fort's wall, by August 21, the British were within 150 yards of the northwest bastion. By the afternoon of the August 22, however, the siege was over and St. Leger's force was in full retreat back to Canada.

The sudden collapse of the British siege was due to the work of two men: Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold, who was leading a relief column towards the fort, and a local loyalist named Han Yost Schuyler. Arnold's force had reached German Flatts by August 20, but was still waiting for reinforcements before continuing on to the fort. Han Yost Schuyler, a loyalist soldier in St. Leger's forces, had been captured at German Flatts during a meeting between loyalist leaders from St. Leger's army and from the German Flatts area. Schuyler was amongst several in the party condemned to death as a spy. Schuyler was married to an Oneida woman and had lived amongst the Indians. Therefore, he was someone the Indians trusted. He also seems to have been a flamboyant storyteller. This may have given him greater sway over the Indians as well. Arnold decided to use Schuyler's influence on St. Leger's Indian allies. Offering Schuyler his life in exchange for his services, he instructed Schuyler to go to the Indian camps and spread rumors about Arnold's force, exaggerating its size and nearness to the fort. Schuyler agreed to carry out this plan.

Sometime on the morning of August 22, Schuyler reached the British lines and began his work. The British had promised the Indians little fighting, a quick victory, and lots of plunder. Instead, the Indians had lost many men fighting against Herkimer's militia, had lost most of their personal property during Willett's sortie, and the British seemed incapable of forcing the fort to surrender. St. Leger did all he could to encourage his Indian allies, but most had lost all interest in fighting or further supporting the British. They also began to complicate the situation even more by breaking into British supplies and stealing from St. Leger's troops to replace what they had lost. Uncertain of the true strength of Arnold's force, and with the situation in his camps falling apart, St. Leger was forced to end the siege and order a quick retreat. Panic seems to have overcome a good part of his force however, and the retreat quickly turned chaotic, with troops scattering into the woods and leaving a good part of the expedition equipment behind. The siege of Fort Schuyler had ended, and without any further attempts by the British to directly control the Mohawk Valley.

National Park Service/Dan U.

- Lowenthal, Larry, Editor. Days of Siege: A Journal of the Siege of Fort Stanwix in 1777. Eastern National, 1983, Third Printing 2005

- Luzader, John F. Fort Stanwix: History, Historic Furnishings, and Historic Structure Reports. Washington: Office of Park Historic Preservation, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 1976.

- Scott, John Albert. Fort Schuyler and Oriskany. Rome: Rome Sentinel Company, 1927.

- Watt, Gavin K. Rebellion in the Mohawk Valley: The St. Leger Expedition of 1777. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2002.

- Willett, William M. A Narrative of the Military Actions of Colonel Marinus Willett, Taken Chiefly From His Own Manuscript. New York: G.C.H. Carvill, 1831.

Last updated: October 10, 2024