Last updated: February 26, 2024

Article

Permafrost Thaw Slumps in the Noatak Valley

The Noatak River Valley in the Noatak National Preserve and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve is a hotspot for retrogressive thaw slumps (RTS). These small landslides are dramatic features of the Arctic landscape caused by thaw and subsidence of permafrost, followed by downslope flow of liquified sediment and water (Figure 1). Most RTS are located near a stream or lake, and they can have dramatic effects on water quality. The NPS Arctic Inventory & Monitoring Network monitors RTS and other aspects of permafrost and landscape change in the five national parklands in northern Alaska.

Key Findings

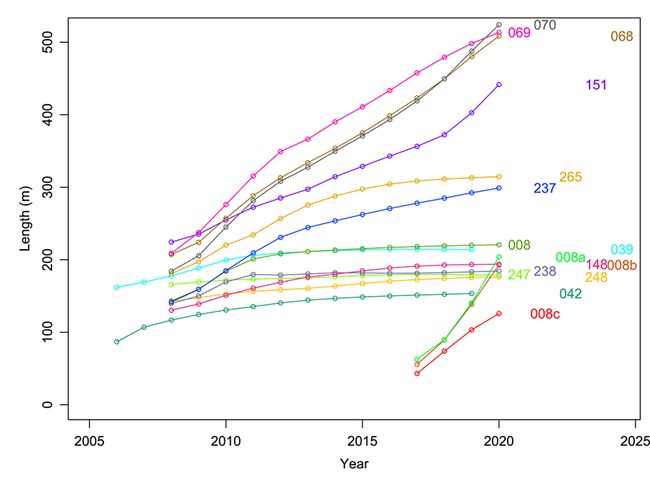

- Many retrogressive thaw slumps were initiated around the year 2005 and grew very rapidly at first. Some have stabilized, while other continue to grow at a steady rate (Figure 2).

- Sediment inputs into adjacent water bodies from the 2005-era slumps are greatly reduced now compared to their first few years of activity. Some slumps are stable and revegetating, while in others the thaw, flow, and deposition of mud continues but now occurs far from any water body.

- Rates of growth in RTS that are still active have been fairly steady in recent years, in spite of climatic warming.

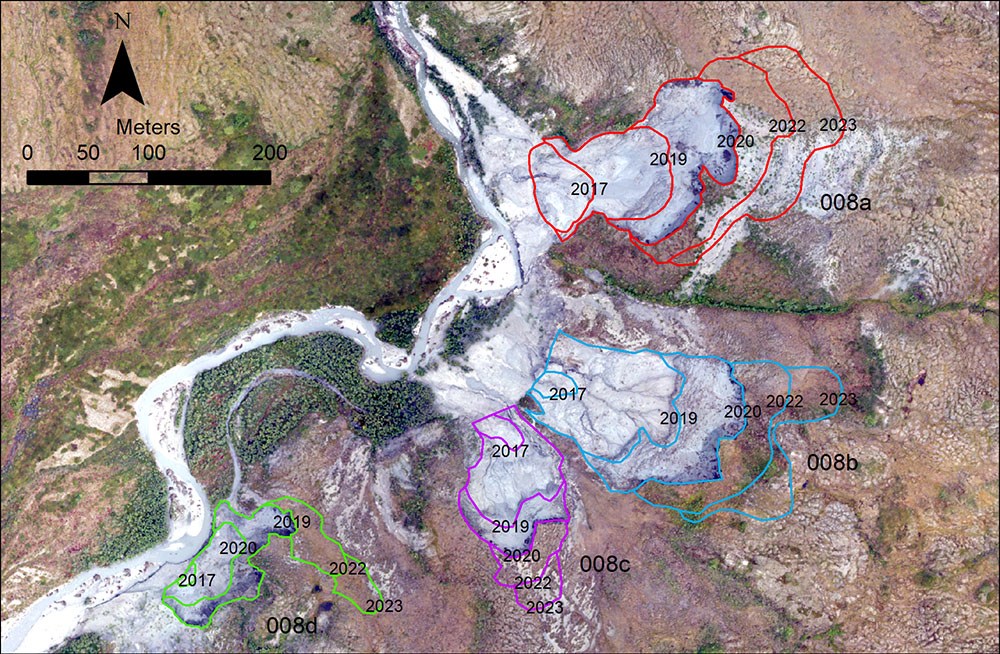

- Four new RTS appeared in 2015 or 2016 along Douglas Creek, on the border between Noatak and Gates of the Arctic (Figure 3). These slumps grew very rapidly: the escarpments at their upper ends migrated from 100 to 200 feet (30 to 60 m) per year, and scarp faces were as high as 33 feet (10 m).

- Between 2015 and 2020, about 180,000 cubic yards (137,000 m3) of material was lost from the Douglas Creek slumps, while about 35,000 cubic yards (27,000 m3) accumulated by the creek, forcing it to move as much as 80 m to the west. The missing 145,000 cubic yards (110,000 m3) of material was sediment and melted ice, carried away by Douglas Creek.

How We Monitor Thaw Slumps

We monitor permafrost thaw slumps and slides using aerial photographs and satellite images. We analyze change in two different ways:

- About every 10 years we map the area of thaw slumps and slides over large areas of our parks to determine if they are becoming more or less widespread.

- We have chosen about 15 large, high-impact RTS to monitor more intensively.

Our aerial photographs are taken from a small airplane flying low enough for us to see objects as small as 4 inches (10 cm). We take numerous overlapping photographs that can then be processed by computer software to produce three-dimensional (3D) pictures of the slumps. From the 3D data we can follow the growth of the slumps in both area and depth. Satellite images are available that allow us to measure growth (in area only) of the slumps in years when we lack aerial photos. Our images of the slumps begin in 2006 or 2008 and continue to the present.

Management Implications

- Since 2016, impacts to water quality and river channels from the numerous 2005-era thaw slumps have generally been minor and decreasing with time.

- Four new slumps near Douglas Creek had major impacts on water quality that probably peaked during 2016-2020 and then decreased, as the active part of the slump moved away from the creek.

- The Douglas Creek slumping was an isolated, local event, probably initiated by stream erosion. Its impacts were limited to Douglas Creek itself and the Noatak River, especially near the creek’s mouth.

- Permafrost thaw slump impacts have been minor in recent years, but slumps could re-activate at any time if unusually warm or wet weather occurs.