Last updated: July 12, 2020

Article

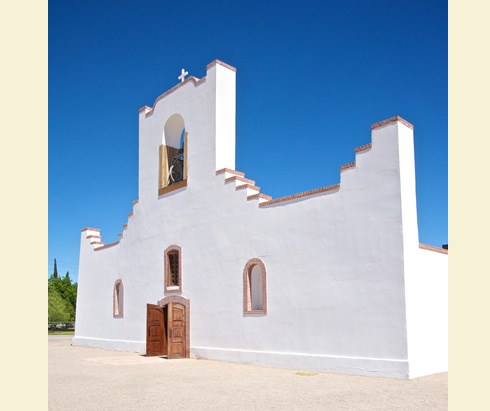

Texas: Socorro Mission

Weathered wooden crosses and marble headstones punctuate the cemetery that fronts the graceful stepped facade of the 1843 Socorro Mission, just south of El Paso, Texas. Highlighting such surnames as Domínguez, Armendariz, Apodaca, Peña, López, Nuñez and Holguin, the cemetery documents over a century of life and death in the 17th-century settlement of Socorro del Sur, located on the southern segment of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, locally known as the Mission Trail. The cemetery only tells part of the fascinating survival story of the Socorro Mission of Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción (Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception) and the community it has served for more than 300 years.

Located in the center of a string of three historic church sites, Socorro Mission rises in the West Texas skyline as one of the Southwest’s best-preserved examples of mission architecture and a place of profound Catholic faith. The mission also draws people of all faiths who dedicate their pilgrimage to experiencing the living history of El Camino Real as it winds through New Mexico and West Texas to its origins in Mexico. As an integral part of a contemporary community on El Camino Real, the mission is a powerful symbol of the region’s unique cultural heritage and a geopolitical history shaped under the governments of Spain, Mexico and the United States.

The mission’s story begins some 200 miles north in New Mexico in 1680. After nearly a century of cultural and religious subjugation by the Spanish Crown, Pueblo Indian peoples revolted, driving Spanish settlers south along El Camino Real to El Paso del Norte (present day Juárez, Mexico) in New Spain. Also fleeing the destruction were a number of Piro, Tano and Jemez Indians who had forged friendly relations with the Spaniards after Spain’s invasion of the province in 1598. Prior to the revolt, many of the Piros lived on ancestral pueblo lands alongside El Camino Real, where in the 1620s the Spaniards established the mission site of Socorro. Spanish for “aid” or “help,” the name recognized the Piros’ provision of food and other assistance to early colonists on the trail.

Arriving in El Paso del Norte, the Spaniards founded a new Pueblo mission community, Socorro del Sur (Socorro of the South), where a temporary shelter served as the church. The village was many miles south of Ysleta del Sur, a mission for refugee Tiwa Indians from New Mexico’s Isleta Pueblo, but a 1683 uprising at Socorro prompted officials to move the community closer to Ysleta. The move led to the community’s first permanent Piro-built church, Nuestra Señora de la Limpia Concepción de los Piros del Socorro del Sur (Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of the Piros of Socorro of the South) in 1691.

The mission replicated 17th-century Spanish New Mexican architectural styles with thick adobe walls, cottonwood vigas (ceiling beams) and corbels, and American Indian decorative elements painted with plant-based pigments. Despite its mass, the church ultimately proved no match for the Rio Grande, which moved forcefully alongside El Camino Real and across the broad floodplain of El Paso’s lower valley. The river’s abundant flows gave way to a prosperous landscape of plant and animal life, thick woodlands and meadowlands, and lush wetlands. Plentiful springtime snowmelt assured fertile soil for local crops. In especially wet years, however, raging floods destroyed buildings and forced area residents to seek higher ground.

Such was the case in 1740 when a flood destroyed Socorro del Sur’s 1691 church. Within four years, the Piros had rebuilt the mission, which now served a community of Indian and Spanish residents who, instead of returning to New Mexico during the Spanish reclamation of 1693, set down permanent roots on the south banks of the Rio Grande. By the mid-19th century, however, the region’s physical and cultural landscape would shift again.

In 1829, another great flood cut a new river channel to the southwest, devouring Socorro’s second church and placing Socorro, Ysleta and neighboring San Elizario on the north side of the Rio Grande. Meanwhile, Mexico’s 1821 takeover of Spanish lands caused significant political change. Further change came with the U.S. defeat of Mexico in 1848. With the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Socorro del Sur became a part of Texas. The Piros were now assimilated into a growing American, and largely Hispano, community that also attracted some Eastern-American settlers. The community included farmers known for their impressive orchards and vineyards, as well as freighters and traders doing business on El Camino Real, then commonly called the Chihuahua Trail.

Changes aside, the mammoth proportions of Socorro’s 1843 mission suggested it was there to stay. Residents again followed 17th-century Spanish New Mexican architectural traditions to build their church, forming massive adobe walls, laying hard-packed clay and gesso floors, and plastering the exterior with lime. Socorro’s American Indian population was smaller, but the church’s unique design details continued to emphasize the community’s Native roots.

Today, these details resonate as a statement of the community’s multicultural history. Finely decorated vigas and corbels salvaged from Socorro’s fallen 18th-century mission boast the red, black and yellow geometric designs of the early Piro artisans who painted them. Painted willow saplings arranged in striking herringbone patterns add to the mission’s dramatic ceiling motif. Perhaps the most recognized native design element is the church’s tall, south-facing facade, an addition in the 1880s. A small window, two statuary niches and a belfry embellish the facade’s broad horizontal span, yet its unembellished stair-stepped effect makes the biggest impression. An echoing of Pueblo pottery cloud designs, the impact is at once abstract, minimalist and monumental.

Another iconic feature is a life-sized Spanish statue of St. Michael that stands to the left of the altar. Church records document the statue’s donation to the church in October 1845 by the Holguin family, some of whose members rest in the adjacent graveyard. According to local legend, however, a trade caravan traveling El Camino Real was transporting the saint from Mexico. After camping at the church, the group prepared to leave, but the wheels of the ox-drawn carreta (cart) carrying St. Michael refused to turn. Neither additional ox-power nor manpower could move the cart, leading residents to believe St. Michael wanted to stay.

St. Michael has since been widely revered as Socorro's protector -- especially after the mission's survival as another flood raged through the area in 1872. However, the end of commercial activity on El Camino Real when the railroad arrived in the 1880s did not spare the community. Nor was it spared the modern development of the 20th century that further fragmented the area. Yet in the 1990s, when years of trapped moisture and deterioration threatened to destroy Socorro Mission, various powers intervened to ensure its protection.

The community launched a full-scale church restoration that resulted in the making of 22,000 adobes to stabilize walls, repairs to the bell tower, and conservation of cherished interiors. After seven years of work, St. Michael resumed his place beside the altar, and the doors of Socorro Mission opened to new generations. With every new baptism or graveyard burial at Socorro Mission today, the story of Socorro del Sur and the legacy of El Camino Real carry on.

Socorro Mission is located at 328 S. Nevarez Rd. in Socorro, TX (20 minutes southeast of El Paso).

The Socorro Mission has been documented by the National Park Service's Historic American Buildings Survey.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.

(Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception) features 17th-century

Spanish New Mexican architectural elements, such as massive adobe walls and lime-plastered exteriors. Photo © Jack Parsons