Last updated: August 14, 2024

Article

The Tenants Whose Residences Raised Two Presidents

Deacon John Adams purchased the properties in 1720 and expanded them over 20 years by inheriting and acquiring nearby land. Over John Adams’ and John Quincy Adams’ lifetimes, the properties regularly switched hands within the family until they moved out entirely in 1806. Although the homes stayed in the Adams family for another 200 years, they were periodically wholly or partially leased to other settlers.

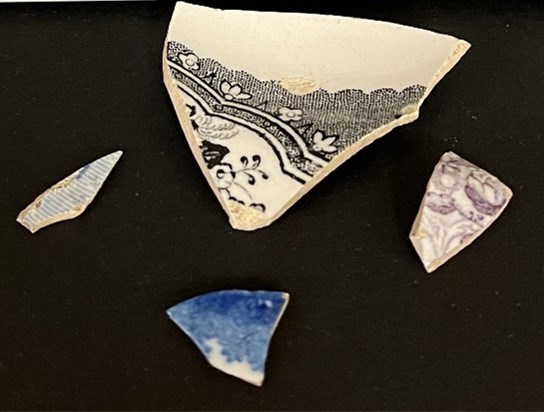

Here these tenants conducted a wide range of businesses, including a private school, an apothecary, and multiple shoemakers’ shops. It is their marks, not the Adamses’, that are most prominent in the archeological record. Through the remains of occupants’ structures, trash, and professional goods, archeology demonstrates the changing influence of tenants on the Adams birthplaces and the community that flourished around them.

The Evolution of Two Homes

After his father’s death from influenza in 1761, John Adams inherited the future John Quincy Adams Birthplace along with forty acres of farmland. In the years following his marriage to Abigail Smith, John Adams purchased new tracts of land and eventually acquired his birthplace too, though his growing political career frequently drew him away from town. As he and his family spent more time abroad, maintaining his extensive land holdings, particularly the farmland, became unsustainable. To ease his parents’ financial burden, John Quincy Adams assumed ownership of the now ninety-one-acre farm in 1803. After his family moved out in 1806, the properties were never occupied by one party for long.A 1980 geophysical survey and series of archeological tests and a 1983 monitoring project conducted by NPS archeologists looked for evidence of the many people who temporarily called the birthplaces their homes. The 1991 Archeological Collections Management Project compiled findings from both projects to re-analyze structural features and identify a total of 31,699 artifacts from four collections.

West of the John Adams Birthplace yielded a concentration of domestic refuse from the 1700s through the 1900s. The items, which may have been dumped after a fire, included doll fragments, toys, and a whole teacup, reflecting the active and varied use of the house lots. Even so, there is no direct evidence of the apothecary shop established by the wife of shoemaker Tom Hayden, nor is there any for the private school that Sukey Burrell operated out of the building in 1833. They may have simply been open too briefly to leave a trace.

Archeology Beyond the Ground

The faint vestiges of these tenants and the Adamses themselves are incomparable to the clear legacy of shoemaking activity at the birthplaces, for which clues appear in an unlikely place.The earliest shoemaker in residence was none other than Deacon John Adams, a cordwainer and the first of the Adams family in the area. The next to set up shop were cobblers Adam and Samuel Curtis at the John Adams Birthplace in 1820, followed by Irishmen John Harrison and Patrick Hailey at the John Quincy Adams Birthplace in 1850. Neither stuck around for exceptionally long, though their artifacts certainly have.

A Testament to Community

The archeological investigations at the birthplaces attest that no historical place is stagnant. Every alteration, from discarding trash to constructing and modifying additions and outbuildings and recent NPS landscaping, leaves a trail—and the ones that are unexpected or hidden are of no less significance. Although the John Adams and John Quincy Adams birthplaces carry the names of two influential politicians, there are many contributors to the properties’ development. It is thanks to a long score of families and business owners—lawyers, farmers, educators, shoemakers, and other everyday people—that the birthplaces remain a constant in the local community.Resources

Archeological Collections Management at Adams National Historic Site, 1991. National Park Service.Cultural Landscape Report for Adams Birthplaces, 2014. National Park Service.

Northampton Museums & Art Gallery. Concealed Shoes, available at: https://www.northamptonmuseums.com/info/3/collections/61/shoes-2