Last updated: March 28, 2023

Article

Teaching Military Strategy at West Point Before the Civil War

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

On April 12, 1861, the American Civil War began when Confederate forces under General P.G.T. Beauregard ordered artillery fired into the command of his former U.S. Military Academy (West Point) artillery instructor, U.S. Major Robert Anderson, at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. In the coming civil war, West Point graduates were given high command positions in both the United States and Confederate States armies. Some West Point graduates were working civilian jobs when the war broke out. For example, Ulysses S. Grant was working at his father's leather goods store in Galena, Illinois, when he received news of the firing upon Fort Sumter. The skills these officers had previously learned in West Point classrooms soon had a large influence in the battles of the most devastating war in American History. Nevertheless, how effective were the courses in military strategy and tactics taught at West Point?

Between 1802 (when the first graduates finished their studies at West Point) and 1864, a total of 2,046 cadets graduated from West Point. 1,117 of these graduates fought in the Civil War. Out of this number 810 fought for the Union (roughly 72%) and 307 fought for the Confederacy (27%). Oddly enough, three graduates fought briefly for the Union in battle and then switched to the Confederacy.

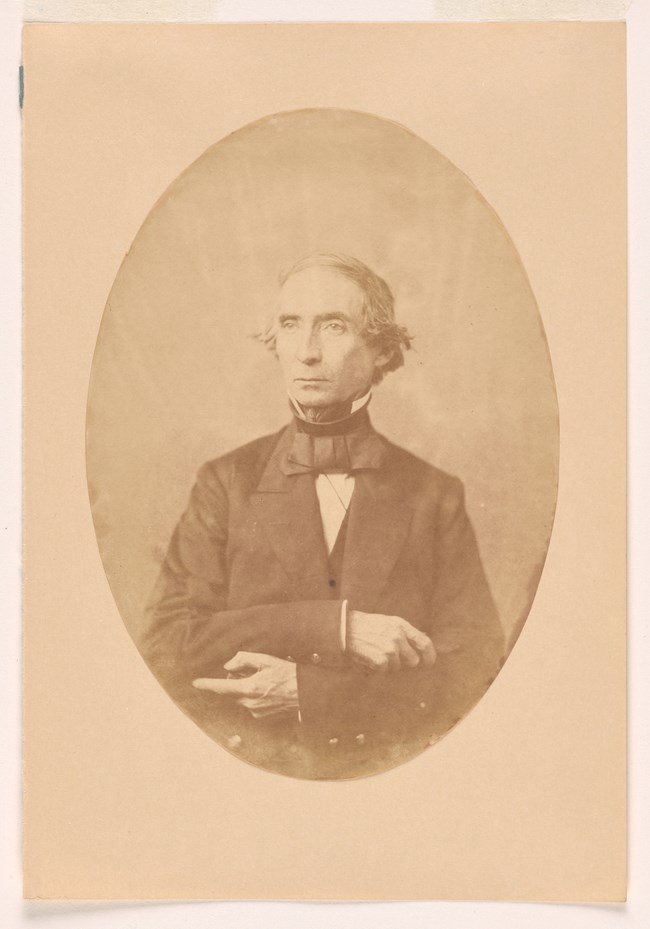

At West Point, most of these officers concentrated surprisingly little on military tactics and strategy. Obviously, academy authorities could not have anticipated that one day these cadets would be fighting against each other. Except for smaller scale wars such as the War of 1812, the Mexican American War, and various conflicts with indigenous peoples, military energy during peacetime was spent on coastal fortifications, frontier garrison duties and various engineering projects. Therefore, the curriculum at the academy focused heavily on mathematics, engineering, and fortifications. During the cadet’s senior year however, they took classes by the famous professor, Dennis Hart Mahan, a respected military theorist and engineer who taught at West Point for nearly forty years. Most Civil War commanders had taken classes from Mahan while cadets at West Point. Interestingly, Ulysses S. Grant (Class of 1843) and his son Frederick Dent Grant (Class of 1871) both took classes by Mahan at West Point.

Wikimedia Commons

Of all the military theorists who were studied at military academies, two stood out. Antonine-Henri Jomini, a Swiss born officer who fought under Napoleon and chronicled his campaigns, and the Prussian general and military theorist, Carl von Clausewitz. Although their writings were around since the 1830s, language was an issue in America since Jomini’s writings were not translated to English until 1852 (roughly a decade before the Civil War) and Clausewitz’s writings were not translated until years after the Civil War in 1873. French was a required course at West Point, but unless one read it fluently, it would be hard to fully comprehend Jomini’s writings. Professor Mahan and future Union General Henry Halleck, who wrote a book entitled Elements of Military Art and Science in 1846, reinforced "Jominian" ideals onto cadets during their studies. Because they weren't translated until much later, Clausewitz’s principles were not a part of academy instruction before the Civil War.

Jomini and Clausewitz’s ideas, although similar on some respects, differed on very important aspects. Jomini, whom more Civil War commanders were familiar with, stressed limited bloodshed by a strategy of “finesse, planning, and maneuver” in his book, The Art of War. This strategy would avoid mass casualties by large armies. His focus was more on attacking strategic points while protecting one’s supply lines. Generals like George B. McClellan, Henry Halleck, and Don Carlos Buell on the Union side and Joseph E. Johnson and P.G.T. Beauregard on the Confederate side utilized these Jominian principles by practicing limited warfare, with McClellan most notably attempting to conquer the Confederate capitol in Richmond, Virginia, rather than directly attacking the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Despite receiving the same training as other future generals while at West Point, Ulysses S. Grant later remarked that “I have never read it [Jomini] carefully."

Wikimedia Commons

Clausewitz’s writings in his work, On War, centered on his theory that “war was politics by other means.” He stressed that the focus should be on the enemy army rather than a strategic point and argued that an enemy strategic point would fall if the army defending it was defeated. Grant espoused this strategy during the Civil War despite probably never reading Clausewitz. An example of Grant embracing a "Clausewitzian" principle lies in when he told General George G. Meade, who commanded the Union Army of the Potomac, “Lee’s army will be your objective, wherever Lee goes there you will go also.” This changed the mindset of the Eastern Theatre of the war where prior generals stressed capturing Richmond as more important than defeating the Army of Northern Virginia that defended Richmond. Grant's embrace of this principle eventually led to General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

The nineteenth century Prussian military commander, Helmuth von Moltke, famously stated in 1880 that “no plan survives first contact with the enemy.” Even though he said this after the American Civil War, this statement rings true in that conflict. Union General William T. Sherman once said regarding the union defeat Battle of First Bull Run (Manassas) in which he led a brigade, “it was one of the best planned battles of the war, but one of the worst fought.” It took an adaptable general, Ulysses S. Grant, who was educated at West Point, but who also adapted his strategy and tactics through experience, ultimately finding the winning strategy for Union forces.

Further Reading

James J. Morrison, The Best School: West Point, 1833-1866. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1998.

Timothy B. Smith, "Ulysses S. Grant and the Art of War," in Chris Mackowski and Frank J. Scaturro, eds., Grant at 200: Reconsidering the Life and Legacy of Ulysses S. Grant. El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie, 2023.