Last updated: August 11, 2021

Article

Tea Chests

Tea has been cultivated and drunk in China since at least as far back as the Han Dynasty, (about 150 BCE). By the 7th century CE, tea had spread to Japan and Korea. Almost a thousand years later, in 1606, the first shipment of tea landed in Amsterdam, beginning a Western obsession with these loose dried leaves that shows no sign of slowing down. Up through the mid-19th century, most of the tea shipped into the United States came from China, but after Japan opened its doors to trade with America in 1859, Japanese tea quickly became half of all tea imported into the United States.

The loose tea leaves were shipped in wooden crates lined with lead foil or later aluminum foil to keep air and moisture out. Asian merchants, knowing that attractive packaging was an important part of marketing, often painted the tea chests or covered them in printed paper with labels that carried the name of the consigner and sometime the name of the ship. Tea chests are relatively rare, considering the number that were produced, but like today’s cardboard boxes, they were either reused or destroyed once they had served their purpose. These three tea chests date from the Japanese trade of the late 19th century.

NPS Photo / Claire Norton

Tea Chest, 1867-1874

Possibly Japan

Wood, paper

Gift, Eastern National Parks and Monument Association

SAMA 2028

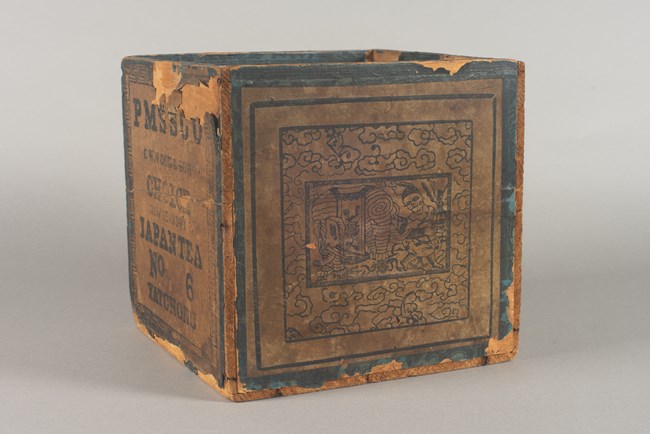

The first tea chest is cube-shaped, about 9 inches per side, and is made from wood covered with paper. All four sides of the exterior of the tea chest are covered by black and brown printed paper. On three of the four sides of the tea chest is an elephant and a man that are interpreted the same way they would be in Indian artwork. Surrounding the elephant and man are clouds that are drawn the same way they are depicted in Chinese artwork. Although the tea chest was most likely made in Japan, the art on the tea chest is an interpretation of both Indian and Chinese design. At this time, the three great tea-producing countries were China, Japan, and India, where the British East India Company had imposed widespread cultivation of tea to compete with the Chinese, and this mix of design reflects the mixing of Asian tea cultures under British influence in the 19th century.

NPS Photo / Claire Norton

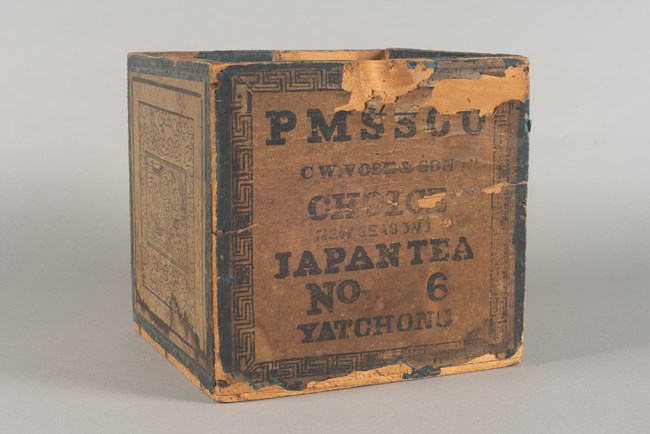

On the fourth side of the tea chest is a label in fading black letters. “P M S S C O” is the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, a steamship line that originally was founded to take mail from the western side of the Isthmus of Panama to California, but in 1867 expanded to include regular steamship service across the Pacific to Hong Kong, Yokohama, Japan, and Shanghai, China.

“C. W. Vose & Son” was a large department store and lumber yard that operated in Machias, Maine between 1864 and 1911. However, the name was “C. W. Vose & Son” only between 1865 and 1874, before being changed to “C. W. Vose & Sons,” which gives us a date of between 1867 and 1874 for this tea chest.

“Choice New Season Japan Tea, No. 6” is the type of tea that is being shipped, highlighting the fact that it is the latest harvest, not old tea, and that this is the 6th box in the shipment for C.W. Vose & Sons. The last word on the label, “Yatchong,” is a mystery. It is not a variety of tea, like oolong, or souchong, so it is more likely the merchant who sold the tea in Asia. “Yatchong” is possibly a corruption of the name “Yat Cheong,” which is a common name in Hong Kong. More research needs to be done to figure out who or what “Yatchong” is, and whether this tea chest originated in Japan or Hong Kong.

NPS Photo / Claire Norton

Tea Chest, 1871-1873

Japan

Wood, paper

Gift, Eastern National Parks and Monument Association

SAMA 2030

NPS Photo / Claire Norton

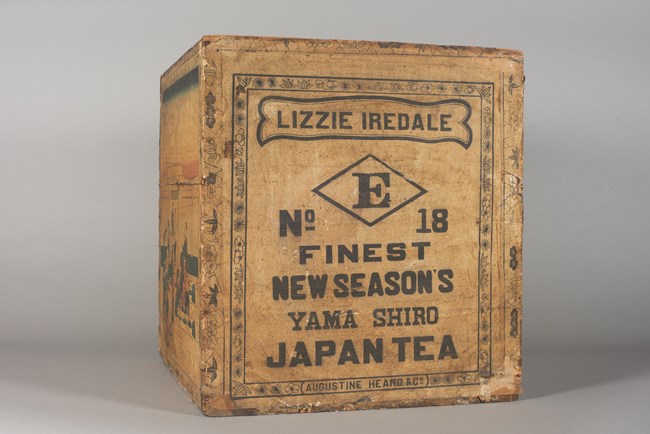

The second tea chest is made out of wood and paper, and is about 16 inches square and 18 inches high. Each side of the tea chest is covered in paper with different designs and illustrations.

Two of the sides of the tea chest depict Japanese women processing tea. In contrast, a Japanese harbor with Mount Fuji in the background covers a third side of the tea chest. These three prints are ukiyo-e woodblock prints in the style of the great printmaker Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), whose prints were a major influence on Western art in the late 19th century. The fourth side of the tea chest is covered by a paper label. Surrounding the label is a border of flowers and plants.

NPS Photo / Claire Norton

The tea chest’s label and the harbor with Mount Fuji in the background along with a notice in The London and China Telegraph announcing the departure of the ship Lizzie Iredale from Hiogo, Japan to Falmouth, England on April 2, 1873 reveals important information about where the tea chest was made, and who owned the artifact.

Augustine Heard & Co. was a highly successful merchant company that was founded in 1840 by Augustine Heard, a member of an Ipswich, MA merchant family, who ran the company until his retirement. After Augustine Heard retired, his four nephews were in charge of running the company. Augustine Heard & Co. engaged in a commission business with China until the spring of 1875 when the company filed for bankruptcy.

The date that the tea chest was imported from Japan makes the tea chest possibly one of the last items that the Augustine Heard & Co. imported. The vessel that transported the tea chest was the clipper barque Lizzie Iredale, owned by Peter Iredale, a British merchant based in Liverpool. The Lizzie Iredale was built in Glasgow in 1868 and sailed for 19 years before disappearing at sea in 1887. A study of shipping notices in British and New York shows that the Lizzie Iredale made only two trips to Japan: in 1871-72, and in 1872-73, so it is most likely that the tea chest was made between 1871 and 1873. Since a British clipper ship transported a tea chest to the United States, it shows that the Augustine Heard & Co. had connections with Peter Iredale. It is further proof that American and British merchants such as the Heard family and Peter Iredale were business partners during the clipper ship era of the 1840s to the 1870s.

NPS Photo / Claire Norton

Tea Chest, 1877-1890

Japan

Wood, fabric, paper

National Park Service Purchase

SAMA 3862

The exterior of the last tea chest is covered with fabric on the front, back, and sides. The fabric is decorated with multi-colored Japanese prints bordered by paper covered by black paint. The images are reproductions of 18th century Japanese prints of a party scene in a garden with women in kimonos carrying fans. The interior is lined with foil. The chest also includes a removable sliding lid with a label that says “Lyons Delaney Co, Pawtucket, R.I.” The same label is on the bottom.

The tea chest was imported to Pawtucket, Rhode Island by Lyons Delaney, a wholesale dealer in tea, coffee, and spices who started his business in 1877 and became Lyons Delaney & Co in 1890. This tea chest would have been a colorful addition to any store at the end of the 19th century and would have fit in well with the taste for Japanese objects and design at that time.

Richard Welch, Intern

Department of History, Westfield State University

“Advertisement for C. W. Vose & Sons,” in Allen, Mrs. Willis H. Machias Cook Book. Machias, Maine: C.O. Furbush, 1899, p. 125.

“Advertisement for Lyons Delany & Co,” Pawtucket, Rhode Island City Directory, 1890.

“C. W. Vose and Sons,” in Bacon, George F. Calais, Eastport and Vicinity, Their Representative Business Men and Points of Interest Embracing Calais, Eastport, Machias, Machiasport, Milltown, Jonesport, Princeton, Millbridge, Cherryfield, and Lubec, Newark, NJ: Glennwood Publishing Company, 1892.

Chandler, Robert J. and Stephen J. Potash. Gold, Silk, Pioneers and Mail: The Story of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. San Francisco: Friends of the San Francisco Maritime Museum Library, 2010.

Heard Family. Heard Family Business Records Finding Aid, 1734-1901. Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School, Harvard University. Accessed May 31, 2017.

Kakuzo, Okakura The Book of Tea, ed. by Bruce Richardson. Danville, KY: Benjamin Press, 2013.

The London and China Telegraph. London, Monday, June 9, 1873.

“Lyons Delaney” in Grieve, Robert. An Illustrated History of Pawtucket, Central Falls , and Vicinity : A Narrative of the Growth and Evolution of the Community. Pawtucket, R.I: Pawtucket Gazette and Chronicle, 1897.

Pettigrew, Jane. Richardson, Bruce. A Social History of Tea: Tea’s Influence On Commerce, Culture, and Community. Benjamin Press: Danville, Kentucky, 2014.