Last updated: February 12, 2024

Article

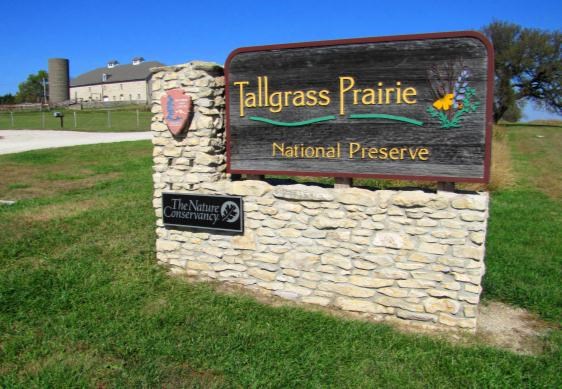

Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Quick Facts

NPS Photo

Establishment

-

In June 1994, at the request of US Senator from Kansas, Nancy Landon Kassebaum-Baker, the National Park Trust purchased the Spring Hill/Z Bar Ranch to assist in the creation of a national park.

-

On November 12, 1996 the 10,894-acre Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve was created as the 370th national park unit.

-

At the preserve’s dedication, Senator Kassebaum-Baker called the preserve a “model for the nation.”

-

The National Park Service will own no more than 180 acres of the preserve, leaving the majority of the preserve’s land in private, non-profit ownership.

-

For nine additional years the National Park Trust and National Park Service developed the park.

-

In April 2005 the National Park Trust completed its mission at the preserve by transferring its land ownership to The Nature Conservancy, who now works closely with the National Park Service on a wide range of tallgrass prairie restoration projects.

-

The Kansas Park Trust assisted in the transfer of preserve property from the National Park Trust to The Nature Conservancy.

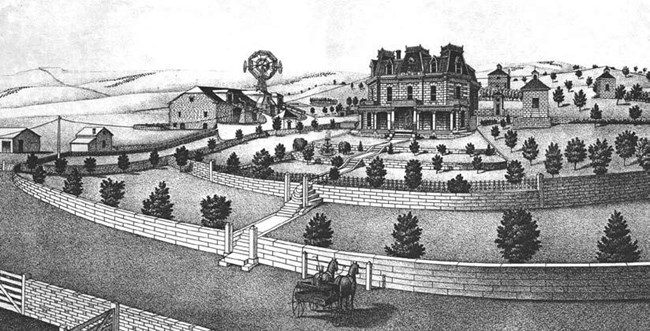

Kansas Atlas, 1887

Spring Hill Ranch

-

Stephen and Louisa Jones, with their fifth child, Loutie, arrive in Kansas in August 1878, to establish a cattle ranch.

-

Due to their success in the beef business in Texas and Colorado, the Joneses have $100,000 ($2.5 million in today’s dollars) to spend on building the ranch.

-

Construction of the ranch buildings began in late 1880 and was complete by early 1882.

-

Eventually the ranch covered 7,000 acres, all of it purchased by the Joneses.

-

Over 30 miles of stacked limestone fence was constructed inside and around the ranch.

-

The Joneses sell the ranch in 1888 to their southern neighbors, Barney and Bridget Lantry, for $95,000.

-

At least eleven owners have had a hand in maintaining the Spring Hill Ranch grounds from the late 1870s to the present.

NPS Photo

Spring Hill Ranch House

-

The ranch house was completed in late 1881 in the French Second Empire architectural style, with the limestone for the ranch house quarried east of Strong City.

-

The ranch house was built into hillside to take advantage of the hillside’s insulating qualities.

-

The ranch house features eleven rooms with 3,500 square feet of living and working space.

-

The ranch house is divided into three main floors with the kitchen area built into hillside between the first and second floors.

-

Telephone service was wired into the ranch house less than ten years after the telephone was invented in 1876.

-

The Joneses lived in the ranch house for only five years, moving to Kansas City in 1886, and sold the entire ranch in 1888 to their southern neighbors, Barney and Bridget Lantry.

-

The ranch house became a work site, residence, and ranch manager quarters in the 1900s.

NPS Photo

Spring Hill Ranch Barn

-

The ranch barn was completed in early 1882 in the German bank barn architectural style, with most of the limestone for the ranch barn quarried a few hundred yards north of building site.

-

The ranch barn was built into hillside to provide a well-insulated environment for animal stables.

-

The ranch barn contains around 19,000 square feet of work and storage space.

-

The first floor was set up as stables; the second floor was set up for farm equipment storage; the third floor was set up for hay and grain storage.

-

Ramps provided access to third floor for horse-drawn wagons.

-

A large windmill once stood between the ramps in the 1880s, but was soon dismantled due to dangerous vibration arising from high winds.

-

The ranch barn was modified with electricity, steel support beams, and other modern equipment in the late 1940s.

NPS Photo

Lower Fox Creek Schoolhouse

-

Stephen Jones donated a portion of his ranch land to build the schoolhouse, while others in the area donated building materials and labor.

-

Construction of the schoolhouse was completed in May 1882.

-

First classes were held in the schoolhouse in September 1884, once a teacher was hired.

-

Classes were held in the schoolhouse until 1930.

-

Class size varied from one to nineteen students from grades one through eight.

-

The schoolhouse reverted to ranch ownership in 1930 and was used as a ranchhand house and for storage.

-

The schoolhouse was restored by local garden clubs in 1968 and was placed on National Register of Historical Places in 1974.

NPS Photo

Kansas Flint Hills Geology

-

Alternating layers of limestone and shale make up most of the rock found in the Flint Hills.

-

Chert, commonly called flint, is found within the limestone, in bands or nodules.

-

The shale erodes much faster than the surrounding limestone, exposing the chert on the surface, and giving the Flint Hills their steepness and characteristic “stairstep” appearance.

-

Scientific estimates place the age of the Flint Hills at nearly 300 million years.

-

Mud and the remnants of marine plants and animals fell to the bottom of ancient seas that would later become the three types of rock found in the Flint Hills.

-

The limestone, shale, and chert occur very close to the surface, making most of the Flint Hills landscape difficult to plow, thereby helping to maintain more of the area’s original character.

-

Chert is very hard and erosion-resistant, making it a very useful toolmaking material for several tribes of Native Americans that hunted bison and other grazing animals in the Flint Hills.

NPS Photo

Kansas Flint Hills Grasses

-

Over 70 species of grasses can be identified in the Flint Hills.

-

Four species of grasses dominate, Big bluestem, Little bluestem, Indiangrass, and Switchgrass.

-

The grasses account for around 80% of the total plant life, but only around 20% of the total plant species found in the Flint Hills.

-

Many species of tall grass can reach heights of four to seven feet, given the right growing conditions and location, reaching their full heights in September and October.

-

Even with an average of 30 to 35 inches of precipitation in the Flint Hills annually, deep, fibrous roots 10 feet long or more help many species of tall grass survive harsh, low moisture conditions, with most of the plant’s biomass found underground, in the roots.

-

The dense network of tall grass root fibers stays close to the surface, binding the soil together like steel in concrete, helping the plant absorb moisture and nutrients.

-

The dense network of tall grass root fibers eventually decomposes into the soil, improving it by capturing immense amounts of organic carbon that could otherwise become a greenhouse gas.

NPS Photo

Kansas Flint Hills Wildflowers

-

Over 400 species of forbs, non-woody broadleafed plants often called wildflowers, can be identified in the Flint Hills.

-

The forbs account for only around 20% of the total plant life, but for around 80% of the total plant species found in the Flint Hills.

-

Many tallgrass prairie forbs are legumes, fixing nitrogen into the soil from the atmosphere, enriching the soil.

-

Even with an average of 30 to 35 inches of precipitation in the Flint Hills annually, deep taproots 10 feet long or more help many species of forbs survive harsh, low moisture conditions with most of the plant’s biomass found underground, in the roots.

-

The deep taproots of tallgrass prairie forbs act like nutrient pumps, bringing nutrients from deep in the ground up to the surface.

-

The deep taproots of tallgrass prairie forbs eventually decompose into the soil, improving it by capturing immense amounts of organic carbon that could otherwise become a greenhouse gas.

-

Many tallgrass prairie forbs, like prairie turnip or purple coneflower, have edible or medicinal qualities that several tribes of Native Americans found valuable.

NPS Photo

Kansas Flint Hills Native Peoples

-

The Pawnee, the Osage, the Wichita, and the Kansa people were all known to have hunted in the Flint Hills, while also collecting and working chert from the Flint Hills for tools and weapons.

-

These Native peoples lived near sources of water and set fires in the Flint Hills to attract bison and other grazing animals to the fresh, new plant life arising afterward on their hunting grounds.

-

The state of Kansas is named for the Kansa people, People of the Southwind.

-

The Kansa, living on ancestral lands and then a reservation near Council Grove, KS, were forcibly relocated 1872 to reservation lands in what would become Oklahoma.

-

The Kansa still exist as a sovereign, tribal nation, called the Kaw Nation of Oklahoma.

-

Four sovereign, tribal nations exist in Kansas, the Prairie Band Potowatomi, the Kickapoo, the Sac and Fox, and the Iowa.

-

The Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, KS, the Kaw Mission State Historic Site in Council Grove, KS, and the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site in Fairway, KS all help to bring Kansas’s Native history to life.

NPS Photo

Kansas Flint Hills Fire

-

Fire is a fundamental part of the tallgrass prairie ecosystem, adapted for use by both the Native peoples of the Flint Hills and by European and American settlers.

-

Fire burns away old growth and gives tallgrass prairie plants greater access to sunshine and moisture.

-

Fire challenges and stimulates the tallgrass prairie grass species to grow stronger, since their growth parts are right on or beneath the soil’s surface, protected from fire.

-

Fire burns away only the top 20% or 25% of the total tallgrass prairie grass plant. The roots are protected in the ground and fire prompts them to grow a fresh, new shoot on the surface.

-

A new method of burning, called patch burning, burns a small area of tallgrass prairie, around 30%, which is then moved from year to year, creating a mosaic of burned and unburned areas.

-

As the burned patches move from year to year, grazing animals follow the fresh plant growth that arises, thereby naturally spreading their grazing activity over a wider area.

-

The unburned areas, which aren’t grazed as much, are given a chance to rest, grow their roots, and store energy, while also serving as ground cover for wildlife.

NPS Photo

Kansas Flint Hills Wildlife

-

Over 35 species of reptiles and amphibians can be identified in the Flint Hills, like box turtles, great plains skinks, collared lizards, Texas horned lizards, and bull snakes.

-

Over 150 species of birds can be identified in the Flint Hills, like greater prairie chickens, dickcissels, wild turkeys, vultures, and red tailed hawks.

-

Over 35 species of mammals can be identified in the Flint Hills, like jackrabbits, bobcat, white-tailed deer, coyote, and bison.

-

Over 30 species of fish can be identified in the Flint Hills, like bluegill, channel catfish, crappie, smallmouth bass, and Topeka shiner.

-

Hundreds of aquatic invertebrate species can be identified in the Flint Hills, like mussels, clams, crawfish, and snails, with many insect species beginning their life cycle in the water.

-

At least 1,000 species of insects can be identified in the Flint Hills, like grasshoppers, butterflies, bees, crickets, and beetles.

-

Much of the wildlife in the Flint Hills depends on the cover provided by the grasses and wildflowers, encouraging close observation and study.

NPS Photo

Kansas Flint Hills Cattle Ranching

-

Cattle ranching forms the backbone of the Flint Hills economy.

-

Spanish explorers and colonists brought cattle, horses, and cattle culture to North America in the 1500s.

-

European and American settlers began building enclosed cattle ranches in the Flint Hills in the 1870s, setting the foundations for present-day Flint Hills cattle culture.

-

The grazing activity of cattle, although different than bison, still serves to stimulate tallgrass prairie grasses to grow stronger, which in turn helps to preserve the tallgrass prairie.

-

Not being native to North America, cattle have a taste for forbs, or wildflowers, with around 30% of their diet consisting of these plants.

-

Modern cattle roundups or “gatherin” in the Flint Hills, and many other cattle ranching activities, look as they did 100 or more years ago.

-

Beginning in May, cattle can graze in the Flint Hills for three months, six months, or an entire year or more, depending on grazing methods and market conditions.

NPS Photo

Bison

-

Bison are the largest grazing animals in North America.

-

Grazing by bison and other similar animals is a fundamental part of the tallgrass prairie ecosystem, stimulating the grasses and other plants to grow.

-

An estimated 30 to 60 million bison once lived in North America.

-

By 1890, less than 1,000 bison remained in the wild in North America.

-

An estimated 400,000 to 500,000 bison now live in North America.

-

Bison are commonly called buffalo, although true buffalo, the cape buffalo and the water buffalo, live in Africa and Asia, respectively.

-

Bison can be dangerous animals, if not given the proper space to behave undisturbed.

-

A bison’s diet can consist of around 90% grasses and similar species, encouraging the growth of forbs, commonly called wildflowers, thereby maintaining balance in the ecosystem.

NPS Image

Useful books and websites

-

Konza Prairie: A Tallgrass Natural History by O.J. Reichman

-

Prairie: A Natural History by Candace Savage

-

Peterson Field Guides: The North American Prairie by Stephen R. Jones & Ruth Carol Cushman

-

Prairy Erth by William Least Heat-Moon

-

Where The Sky Began by John Madson

-

www.nps.gov/tapr - Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve website

-

www.nature.org/kansas - The Nature Conservancy in Kansas website