Last updated: August 29, 2024

Article

A Succession of Priests: Archeology at the Quarai Mission and Convento

People of the Jornada branch of the Mongollon culture are estimated to have settled the region as early as 700 CE in semi-subterranean dwellings called pit houses. As the Mongollon shifted toward the Tularosa Basin around 1100 CE, Ancestral Puebloans began migrating south from the Four Corners region. The Mongollon and Ancestral Puebloans’ overlapping occupations resulted in a heavily mixed culture in the area. Nomadic lifestyles gradually gave way to more permanent settlements, first with aboveground jacal structures made from woven sticks and mud. Builders began to place jacal walls on stone foundations, which inspired Ancestral Puebloans’ transition to residing in complex masonry house blocks, or pueblos.

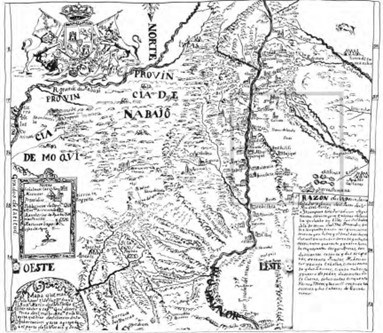

Spanish observers in the mid- to late-1500s and early 1600s wrote little about the cultural traits of the Tiwa and Tompiro peoples they encountered. However, they stressed the region’s abundance of salt and its potential as a buffer against other colonial powers threatening Spain’s domain. Spain’s official entrance into the region brought Catholicism to the Quarai through a sizable Franciscan mission, one in a string of such projects in the jurisdiction.

Coinciding with repair and restoration efforts, archeological investigations throughout the 1900s convey the meticulous design of the mission and the grandeur that still surpasses its neglect. Archeology does not resolve the ambiguities of Quarai’s timeline, but through architectural and human and material remains, it pictures Quarai as it was, not as how one-sided records imagine it to be.

The Nine Lives of the Quarai Mission

Esteban de Dorantes, a formerly enslaved man of African descent, was the first non-native man to visit what is now New Mexico in the 1520s and 1530s. The first Spanish expedition to New Mexico, led by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado from 1540 to 1541, is speculated to have reached the Salinas region but not Quarai. The next documented encounter was not until 1581-1582, when a small party led by Captain Francisco “Chamuscado” Sánchez and Fray Agustín Rodriguez traversed the province. Besides these forays, the Spanish generally left the isolated Salinas region alone until the turn of the century.

Fray Alonso de Benavides is credited as the first priest at Quarai around 1626-1628. His successor, Fray Juan Gutiérrez de la Chica, likely oversaw the construction of Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de Quarai. At its peak, the Quarai pueblo housed between 600 and 700 residents of both Spanish and Native American descent in about 1,000 rooms.

Fray Estévan de Perea, head of the powerful Holy Office of the Inquisition for all of New Mexico, assumed leadership of Quarai in 1633. A few years after his death in the late 1630s, custodianship passed to Fray Juan de Salas, then Mexico-born Fray Gerónimo de la Llana in 1650. Fray Nicolás de Freitas took over from him about a decade later, at a time when the anti-clerical governor of New Mexico López de Mendizábal was intent on making life as difficult as possible for the friars at Quarai.

Fray Freitas’ complaints resulted in the arrest of the ex-governor in 1662, after which Freitas briefly returned to his post at Quarai. Fray Francisco de Salazar was the last to head the Quarai mission before unrelenting Apache raids and years of intense drought and famine pressured the Spanish to withdraw. Finally, in 1677, Fray Diego de Parrada locked the doors to the Concepción de Quarai and joined the wave of Quarai survivors moving north to Tajique.

Some unrecorded and official groups reoccupied the abandoned Quarai pueblo in the 1700s, including Spanish frontier patrols stationed there in the mid-1700s. Other settlers temporarily reclaimed the area in the early to mid-1800s—namely the Luceros families, whose structures used rock lifted from the remains of the pueblos and monuments—but no permanent communities emerged again at Quarai, which has helped preserve the site’s archeological record.

Archeology at Quarai

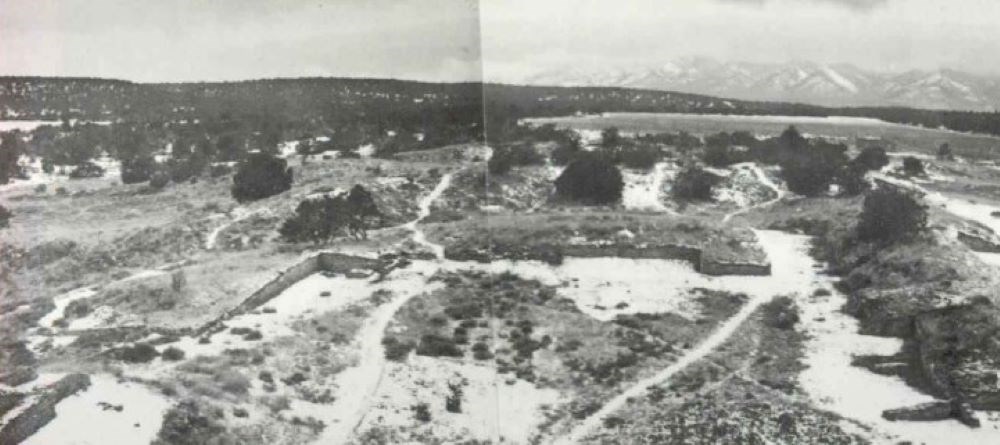

The Summer School of American Archeology, conducted jointly by the School of American Archeology, the Museum of New Mexico, and the University of New Mexico, measured and mapped the church and convento complex between 1913 and 1914. In 1934, the Museum of New Mexico began large-scale excavations in preparation to repair and stabilize the complex. Workers with the Civilian Conservation Corps cleared debris, making visible the rooms of the baptistry, the nave, the transepts, the residence hall, courtyards, and an unusual square kiva—a subterranean Puebloan religious structure—in the friary patio.Wesley Hurt and Works Project Administration workmen continued excavating the pueblo and mission buildings from 1939 to 1940. Examined features point to at least four periods of construction at the complex. The essential religious structures, such as the sacristy, reception room, kitchen, and living quarters of the priests in the west convento section, are presumably the earliest units constructed. Notable structures include an elevated D-shaped one in Room 33, possibly the base of an oven or a wine press; the remains of a circular defensive structure, probably a two-story torreon, or tower; and a grinding bin with three compartments in Room 43.

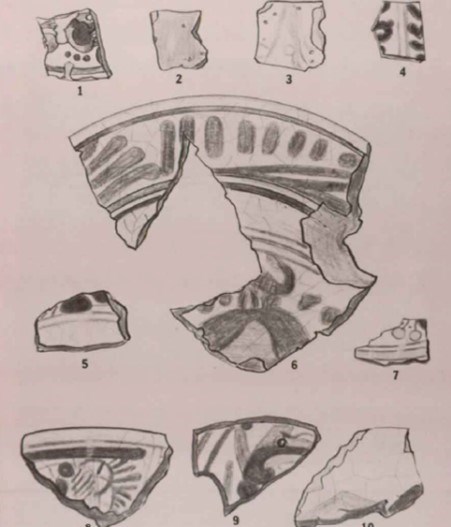

Despite its remoteness, artifacts at Quarai tell of Spanish and nearby Puebloan cultures’ interactions. A variation of Glaze A ware, characterized by a light gray paste and a dark core, was locally made at Quarai and absent from the same type of sherds at the Tenabo and Abó pueblos. Other types indicate trade between settlements. Tularosa Black-on-white, for instance, is a rare type traded to Quarai from the Little Colorado River region.

A clay candle holder, a bird’s head broken from a larger figurine, a highly stylized human figurine, and discs that may have been spindle whorls and gaming pieces clarify the Quarai pueblo as a social—not just religious—center. Nine poorly made miniature clay vessels found throughout the convento rooms may have been the attempts of Puebloan children. Stone and bone beads, selenite pendants, sandstone slabs used to crack nuts, and a peach stone suggest the daily activities like cooking and jewelry-making that made the pueblo largely self-sufficient.

Tricks of Time

Time creates the archeological record but can also hinder its interpretation. Changes in the classification of pottery types, the disappearance of detailed information from previous archeologists’ projects, and the misplacement of notes and specimens from Hurt’s 1939-1940 project reiterate that archeological conclusions are tentative, not absolute.

Certain, however, is the exchange of cultures these artifacts represent. The local copying of vessel forms like soup plates and ring-bottomed cups and bowls demonstrates Spanish influence on Puebloan crafts. Additionally, the Spanish priests adopted locally made pottery and tools like manos and metates, and the Quarai made considerable use of Spanish tools, including knife blades and nails.

Although the Quarai site started as one of many missionary undertakings in New Mexico and ended in the total displacement of its Christian residents less than a century later, archeology makes its physical presence—and the lifeways of all its peoples—indelible.

Resources

Excavations in a 17th-Century Juman Pueblo: Gran Quivira. National Park Service, 1964.History of Quarai. National Park Service, 1940.“In the Midst of Loneliness”: The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions. National Park Service, 1998.The 1939-1940 Excavation Project at Quarai Pueblo and Mission Building. National Park Service, 1990.

Wolfe, Jeanette L. "Salinas Pueblo Missions: The Early History,” 2013. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/86