Last updated: October 3, 2022

Article

Student Life

The following article was originally published on Smith Court Stories, a digital classroom for teachers and students. Please visit the digital classroom for more articles about the education of Smith Court

City of Boston Archives

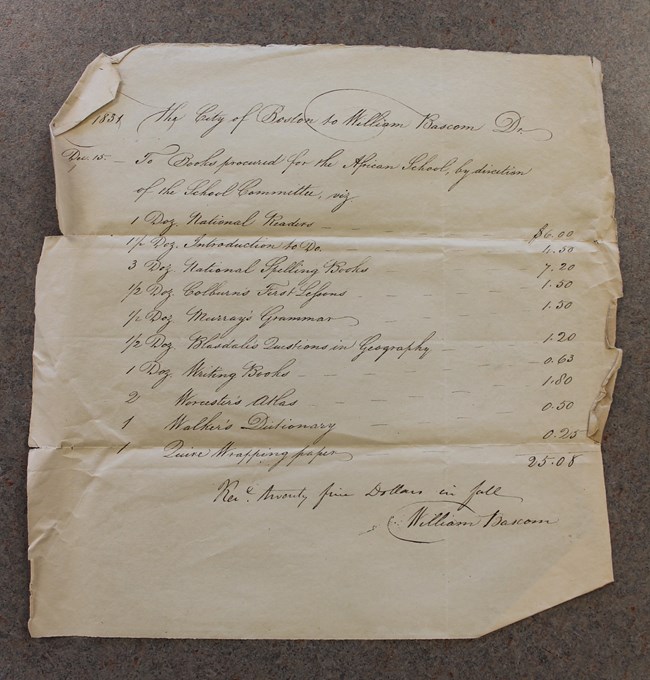

The opening of the Abiel Smith School marked a shift in the education of Boston’s African American children. The city, for the first time, made an investment in the education of these children. When it moved from the African Meeting House to its own building in 1835, the upper floors housed the grammar and writing halls, while the lower level housed the primary school for younger children.[1]

Students received a general education as they learned how to read, studied geography, and practiced writing and grammar. Book lists for the Abiel Smith School offer a sense of the scope of schooling. Notable educational books of the time included Murray’s English Grammar by renowned American grammarian Lindley Murray and Colburn’s First Lessons, an arithmetic lesson book by local educator Warren Colburn.

To practice spelling and arithmetic, students used slate boards and slate pencils that could be cleaned with a rag. An archaeological dig behind the Abiel Smith School, near the privies shared with the African Meeting House, uncovered the slate and pencils pictured here.

National Park Service

National Park Service

When students advanced from practicing on slates, they eventually started writing and bookkeeping exercises with ink pens and paper. These lead inkwell casings and glass inserts held the ink students used. The inkwells sat in small holes cut into the students’ desks.

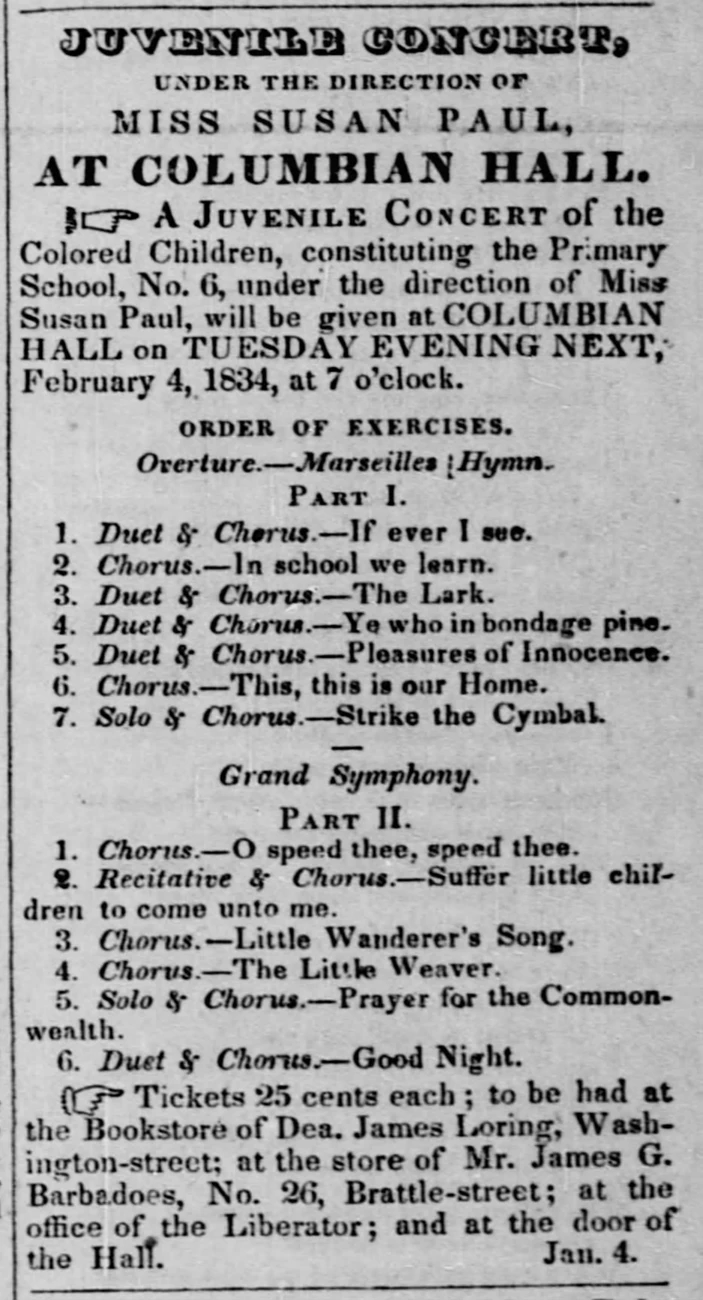

In addition to a general education, students at the Smith School received instruction in moral piety.[2] Boston teachers began and ended the day with prayers, and they taught students hymns and lessons from passages in the Bible.[3] Abiel Smith School teacher Susan Paul recounted her moral instruction in the Memoir of James Jackson. In this retelling of the short life of an African American school child, Susan Paul only named the Bible as a book of instruction, and she included several hymns students learned at the time.[4] Historian Kabria Baumgartner notes how Susan Paul used the Bible as her guide and “[focused] on the Ten Commandments and hymns, to impart lessons on empathy, honesty, and selflessness.”[5]

National Park Service

This moral education aligned with some Smith School teachers’ interest in incorporating civic action into their curriculum. They likely discussed slavery and bestowed the ideology of the abolitionist movement onto their students.[6] Susan Paul took her students to meetings of the New England Anti-Slavery Society where they listened to abolitionist lectures.[7] She also organized the Boston Juvenile Choir with her students, in which they fundraised for the abolitionist movement.[8] Performing concerts at locations throughout Boston, this choir sang hymns that “advanced the abolitionist cause, denounced racial prejudice, and celebrated black intellectual achievement.”[9]

The Liberator

National Park Service.

Similar to schoolchildren today, students at the Abiel Smith School had the opportunity to play games together when not in classes. Archeological digs unveiled gaming pieces, marbles, and a hopscotch stone. Marbles could have been used for both fun and education; teachers may have used marbles to help teach arithmetic while children would play marble games, including “Picking Plums” or “Capture,” in their free time.[10] In addition to the versatile marbles, children could also use the gaming pieces and hopscotch stone in numerous different games. These artifacts confirm that children considered the space of Smith Court as more than just a place of learning, but a place for fun and socializing.

National Park Service

These primary sources and archaeological artifacts provide clues to the school life and education of students who attended the Abiel Smith School. Students received a broad intellectual and moral education while also finding time to socialize and play games along with other children.

Footnotes

[1] Barbara A. Yocum, "Smith School House Historic Structure Report," Boston African American National Historic Site (Boston, 1990) 16.

[2] Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (New York: NYU Press, 2019).

[3] Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge.

[4] Susan Paul, Memoir of James Jackson, edited by Lois Brown (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

[5] Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge.

[6] Paul, Memoir of James Jackson, 13.

[7] Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge.

[8] Susan Paul, Memoir of James Jackson, 11.

[9] Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge.

[10] Abiel Smith School Digital Catalog, Northeast Museum Services (2019).